96. Spring Returns

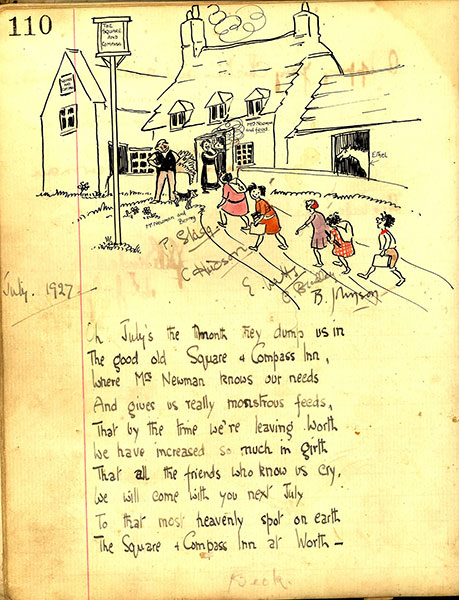

95. The Square And Compass

March 6, 2025

97. Punfield Cove

May 7, 2025S pring comes round again; never unduly different, never failing in its bright beauty. There is a certain degree of competition as it opens. Who spots the first of what? Robert, a friend from childhood, has already beaten me by seeing brimstone butterflies, swallows and the first wheatear. I have won with a whitethroat and the first puffin. Since boyhood, the first Purbeck puffin always appeared in early March, for years our earliest record being 1st March. A couple of years ago I pushed that back to 14th February. This year a couple of puffins were bobbing off the cliffs on 28th February. No, that’s nothing to do with global warming, more to a change in my habits. As boys, we’d go ‘up cliff’ after school, say 5 o’clock or, at weekends, in the morning. Now, living closer to the cliffs, I invariably visit them in the morning, as do most auks.

While working at the quarry, the usual place to score the first wheatear was on the walls beside the rough track running out there. Trev’s father claimed that they often arrived with the first fog of March. One would fly up from the wall, flashing its white rump, and flit along the track ahead of the van only to land a short distance further on. They never learned, always having to fly off again when the van reached their new perch.

Wheatears’ arrival on migration from Africa was welcomed by folk along England’s south coast; although small, they were trapped for food. Little shelters to attract them were set with horse hair nooses, which snared inquisitive birds. In Sussex, during the 18th and 19th centuries, shepherds caught thousands, selling them ‘for 3d (a modern penny – one rupee) a dozen’. The 18th century naturalist, Gilbert White wrote ‘…vast quantities…are .. caught… near Lewes (Sussex), where they are esteemed a delicacy.’ That was true also of Purbeck and Portland. Such trapping is now illegal in Europe but, like many other migratory birds, they are still trapped and shot in huge numbers along the Mediterranean coast. As they fly north, the ducks, geese and waders, which winter in England, leave northwards, setting off for their Arctic homes.

It is all part of Spring to go in search of new arrivals. This year, I’ve done my best with the wheatears, walking along the chalk ridge towards Corfe Castle on suitably foggy mornings but seeing none, only singing larks and meadow pipits. One morning, approaching Corfe just as the castle emerged from fog into sunshine, a raven flew towards me out of the mist.

Following the fences which line Purbeck’s south coast is also a favourite place to spot early migrants, but still there have been no wheatears. That south coast, its slopes now rich in golden, flowering gorse bushes, has the added attraction of seeing sea birds checking their nesting sites. I’ve spotted the three Purbeck auks, but no kittiwake yet. And with April here, I scored no March wheatear, either.

Nearer home, it is time to dig the garden, although that is considered undesirable these days. Hard to teach an old dog new tricks! The onion sets are in: these sets are tiny bulbs, their development artificially stunted, which are more reliable than seeds for producing a good crop. Onions keep pretty well in a cool, dry place, so a few kilos remain from last year’s crop. The broad beans are coming up – a relief after the disaster of last year’s wet spring (see Blog 88) when squirrels ate every bean seed. Then, it had seemed that the garden would never yield another crop. The won’t be ready to eat for a couple of months, but this year the omens are good.

Most of the other early seedlings need a warm environment to geminate, so they are in pots and trays along the windowsills indoors and include chilli, maize, courgette, squash and tomato seedlings. The unheated greenhouse is warm enough for some vegetables: in there already are tiny lettuces, spinach, broccoli, brussels sprout, leek plants. Our climate is too cold for these to thrive in the garden before May.

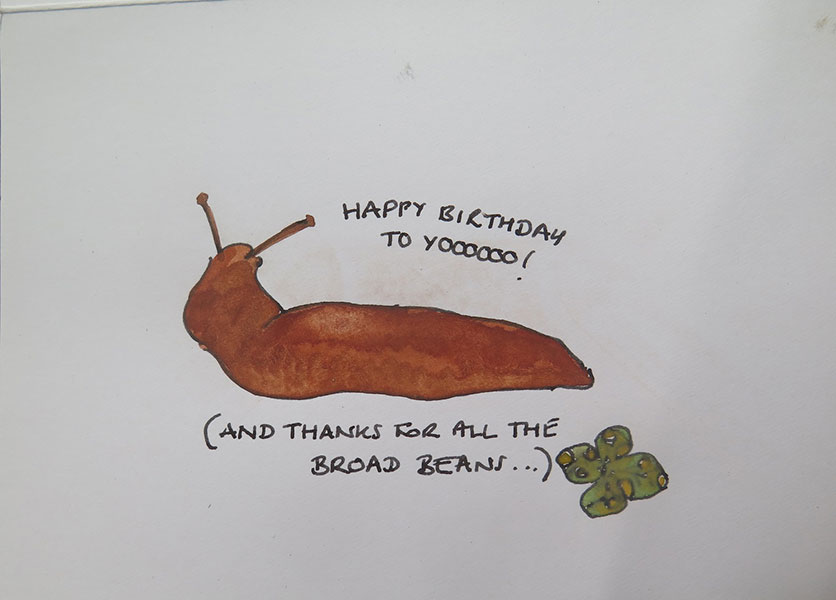

Meanwhile, the enemies are ready: a beautiful pair of bullfinches display their worst feature as they work through the plum tree eating the buds, reducing the chance of a good crop of plums. I shout at them and they fly off, but they are too lovely to want to lose them. In any case, it is the hated squirrels which will eat most of the fruit as it ripens. No rabbits have appeared yet but no doubt they will turn up as soon as all the young plants are at their most vulnerable! HOWE slugs may not be too bad this year thanks to sharp frosts this March. My cousin, Sophie, setting up a vegetable bed in London, is beginning to learn about slugs. She even sent me an appropriate, home-made birthday card. Meanwhile, I’ve just been out to scare the destructive bullfinches off the plum tree again, they get away with murder by being so handsome.

Most of the other spring life is harmless and attractive. Many birds, such as the little warblers that arrive from Africa, are useful since they eat insects that attack plants. The blue tits, that nest in a box in plain view from my desk, also have a taste for insects. A good year for flowers – the snowdrops are almost over but the banks are covered with a mass of primroses and, in the shade of trees, bluebells and white wild garlic flowers afre starting to open.

The greatest charm of spring is the increasingly warm, sunny weather. The season for lying in the sunshine has come and soon the sea will be warm enough for swimming. With luck, there will be calm weather for my little rowing boat to try for some fish. Mackerel are the most popular seasonal catch, appearing in shoals along Purbeck coasts from the end of April. They are in pursuit of smaller fish, so it seems only fair that they, too, should get eaten. Streamlined and fast swimming, they will chase anything that moves so, including bright lures attached to my line, so I can catch fish whilst rowing. The other common species is pollack. Less migratory, they escape winter cold by moving into deeper, milder water.

*