99. Jagmalpura’s Sad Temple

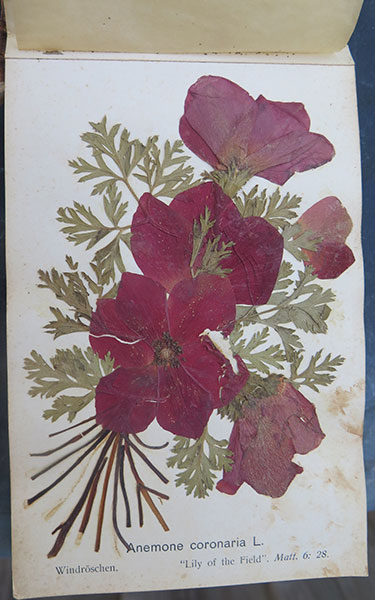

98. Where have All The Flowers Gone?

June 5, 2025

100. Blackers Hole

August 12, 2025T his blog is remarkable for the poor quality of some images. Look carefully, and each should tell its story. As I travelled through Shekhawati, certain of the painted buildings left a deep impression. One such was the Gopinath Temple at Jagmalpura, a tiny hamlet about 6 km north of Sikar. Ravindra Sharma and I found it, on 28th November 1986, while carrying out the INTACH Shekhawati survey. In Sikar, the Gopinath Temple proved heavily painted. Amongst the usual religious pictures was even a view of Jaipur, showing the 1799 Hawa Mahal and local nobility, including Rajas Chand Singh and Shiv Singh, thus post-dating 1800. These pictures have all been overpainted. The present building was constructed by Raja Devi Singh, probably around 1785. Since we showed interest in his temple, the pujari mentioned another, similar but older, at Jagmalpura, telling us how to get there.

I always sought isolated buildings to provide a break from our daily work in busy towns. Jagmalpura was near Sikar, where we were currently based so, a week later, we went there. The rough track the pujari described led through farmland and passing near the derelict temple. It was raised on a slight hillock and built on a platform of hardpan ashlar. Around it stretched green winter wheat. There was a sikhara tower at its western end and a four-pillared Garuda mandap of red sandstone to the east. From there Garuda, his vahana (vehicle), had watched over Gopinathji, one of Vishnu’s avatars. Below and beside the north east corner of the temple was a damaged stone kirtistambh – a memorial pillar – which should have born details of its patronage and date of foundation, but there was no inscription, merely a couple of relief deities, Ganesh and perhaps Kali.

Who built the place? They said it was a Sikar ruler, but those they named were born after its foundation. Perhaps Daulat Singh was its patron, but we were never sure. Harnath Singh, in his ‘Shekhawats and their Lands’ p62, speaks of him and the small estate of Jagmalpura, into which one of Daulat Singh’s mares once strayed. The Thakur of Jagmalpura caught the horse and beat its groom, so Daulat Singh evicted the thakur. He also mentions that Daulat Singh founded Sikar in 1687 and there built a temple. Could he have taken Jagmalpura in the early 1680s, founded a town there and built this Gopinath Temple? Surely, he wouldn’t start work with such a major temple. If it was desecrated shortly afterwards, he might have abandoned the site and founded Sikar not far off: suggestions based on very little fact.

Sikar’s Gopinath temple was constructed seven years after an initial first small Shiva shrine. The town thrives all around it. In Jagmalpura nothing stands apart from a few simple homes. To explain its temple’s dereliction into dilapidation, local kids claimed the deity had been stolen six years back, but that must have been some recent replacement figure. The building had met its doom centuries earlier. They said the kirtistambh used to call out when thieves came to the area, but had been silent since bad men cut off its top. The uppermost stone certainly looked alien, drawn another structure and precariously balanced here. They indicated two deep cuts on its stem as left by the attackers, but these appeared to be merely an attempt to hone a blade there.

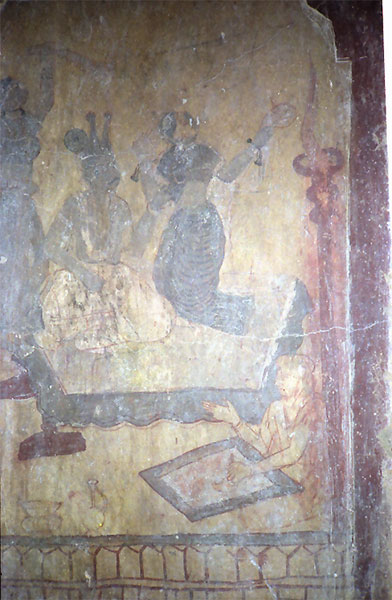

We looked at paintings, visible despite the interior’s rich coat of soot, and filled out the required INTACH form. Using the Christian calendar, graffiti gave an earliest date as 1684, fitting well with Daulat Singh’s rule and making this among the oldest surviving painted buildings in Shekhawati. The graffiti named a Badshah, his name unclear. A little panel high on the internal west wall appeared to depict emperor Aurangzeb (1658-1707). Small portraits of him appear in several old Shekhawati buildings; one, in Nathusar (also in Sikar district) is labelled ‘Narang Shah’. The boys pointed out a very fragile room north of the sanctum’s porch as the the pujari’s kitchen, then led us up to the roof and its sikhara, from which Sikar’s fort was visible. Two rough wooden ties remained across the interior of the hollow tower, which was floored with a great pile of pigeon dung, a neglected supply of excellent manure for their vegetables.

I visited the place several more times. The temple, apparently close to collapse in 1986, stood unaltered thirty years later, when I arrived with Kavita Chaudhary, daughter of my old friend, Nand Kishorji, founder ‘Jaipur Rugs’. We spent a day looking at those sooty walls. The most striking figure, historically, is Aurangzeb seated in a jharokha. Full of the bland intolerance of men crippled by religion, to which modern Gaza is a living monument, he stood in direct contrast to his free-thinking great grandfather, Akbar, thereby helping the Mughal empire to its demise. In May 1679, on Aurangzeb’s orders, Khan Jahan Bahadur passed through the Hindu-ruled kingdoms of Jaipur and Jodhpur, desecrating and demolishing Hindu and Jain temples. Perhaps he destroyed the beautifully-carved Harash Temple near Sikar, perhaps desecrated Jagmalpura’s temple, wrecking any plan to create a town here.

What of other paintings? Some sort of flying angel and at least one putti, float faintly in the entrance arch of the temple. Appropriate for such a temple, several panels show Krishna as Gopinath, teasing the milkmaids. There is a large, battered portrait of a man in a bulky turban. A mosque-like building complete with two minarets is remarkable in housing a Shivling, which might well have upset Muslim sensibilities. One picture shows a man seated on the floor painting, with his left hand, a couple illuminated by a flaming lamp. Laila and Majnu feature, illustrating the sufi love story in which she represents the beloved deity and he the loving worshipper maddened by obsession for his god. Amongst the labelled figures are Namdevji and Kalandaji playing a trick. Faint dado panels show a yellow lion on the red ochre ground.

In the Garuda Mandap, painted in red ochre on the squinches of the little dome, remained three of once-four putti, the little winged heads Mughal art borrowed from the European Baroque. Jahangir left surviving examples in Agra’s Rambagh. Perhaps from there some had fluttered into this building.

Sometimes a building sets a challenge. This doomed temple requires conservators to work carefully with the latest scientific methods to remove the soot and preserve, then record, these historic paintings. Some are labelled and there is graffiti to record. Is no one interested in cleaning, then interpreting these paintings? I’ve mentioned this temple to Indians and foreigners. They seem interested, but I’ve never heard of anyone actually looking at it.