100. Blackers Hole

99. Jagmalpura’s Sad Temple

July 3, 2025

101. On The Rocks

September 15, 2025W here did the name come from? There is no record of a local man named Blacker, but the place shows up as an area of darkness when seen from St Aldhelms Head. Perhaps that was the origin: more poetic folk used to refer to it as Black Arsehole. There are three ways to access the place: a precarious climb down the cliff into the quarry, which gets more challenging every year. The men who worked it slightly improved the access, smoothed a rocky track to a crane which was set up to lower block into boats. They even worked little channels from puddle to puddle across the quarry’s sloping floor to collect rain water. Worked holes near the crane and a clutch of rusty iron wedges jammed into a crack beside the cave formed places to tie up a boat. Occasionally, in summer, we swam from Dancing ledge then had a rough barefoot scramble over rocks with another swim across the cave. On calm days we came from Chapmans Pool by boat. For us, with a small dinghy, even that could be tricky, rowing round St Aldhelm’s Head and along the coast.

I came there first in 1957 with my friend, Treleven Haysom, when amongst the guillemots on the only breeding ledge there was a bird in trouble. At first, we thought it had been shot, but its hanging indicated it was entangled in fishing line. No auks bred in Blackers Hole that season. Each May, I climbed down, originally to collect Herring gulls’ eggs for eating, punishment for those gulls preying on other birds. To reach the nests required swimming some 15 m, using a shirt with its sleeves tied to carry the eggs and not leaving it too late so that they were fresh. Over seventy years the place has proved good for watching the fluctuation of Purbeck’s sea bird population. In 1956 there were guillemots, razorbills, shags and herring gulls nesting there. They remain but, In 1978, were joined by several gull-like kittiwakes, which increased rapidly over the years. They are now fading away, no longer succeeding to raise young there.

We soon worked out the guillemots’ breeding pattern. Summer plumage birds started visiting the ledges in October from wherever in the Channel they wintered. In the 1950s the first eggs appeared around St George’s Day - 23rd April. A recent writer claimed that, due to global warming, the guillemots he studied in Skomer now lay two weeks earlier than previously. I doubt that. Those birds’ habits must be much like ours and here our records agree with more recent ones from nearby Durlston Country Park, where the first guillemot eggs are still laid around St George’s Day, as are those of the herring gulls.

Purbeck’s guillemot and razorbill populations reached their lowest ebb around the late 1950s, when beaches were marred by waste oil, largely due to spillage from ships. Then, three of us boys received RSPCA “gold” medals ‘For Kindness’ for cleaning and tending oiled birds. Strictly controlled, oil pollution is rare now, replaced by the discharge of less plentiful, but equally lethal, palm oil waste.

Annual counts taken between mid-May and June, at the height of the breeding season, give a good indication of sea bird populations. I’ve concentrated on counting Guillemot numbers between 1957 to 2025, but often missed the breeding season. Trev also kept a record of sea bird numbers, some published in his 1976 paper in ‘Proceedings of the Dorset Natural History and Archaeological Society’. When possible, I have drawn on his dates.

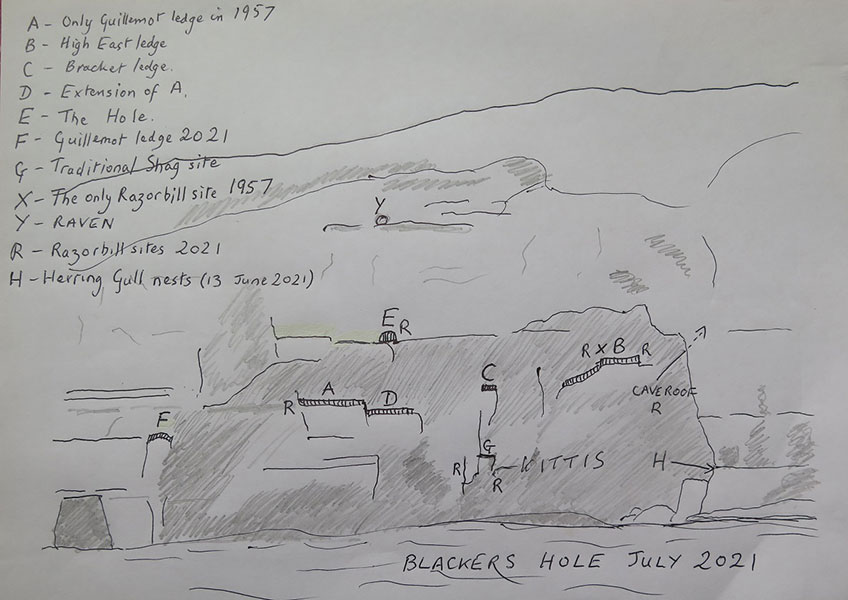

From 1956 to 1995 Blackers Hole guillemots only bred on one ledge, which I later called ‘Trad ledge’. This supported a maximum of 15 pairs. In the early 1990s, they started to settle on another site, ‘High East Ledge’. One laid there in 1996, and before long it became Blackers Hole’s most populous ledge. Since 1956, a small hollow on that ledge was already settled by a pair of razorbills; they have nested there every year since, surviving the invasion of a colony of kittiwakes and then one of guillemots. Around 2010 a larger, more promising ledge west of ‘Trad’, is now my ‘Far West’. Guillemots have laid there, but seem to fail to raise young each year, probably due to predation. In 2016 guillemots took over a small ledge which became ‘Bracket’. In 2019 the ‘Trad’ colony extended eastwards along a slightly lower ledge. In 2021, high above it, in a dark hole in the cliff which used to house a shag’s nest, a couple of pairs of guillemots settled alongside razorbills. There is no room there for any more. In 2023, a pair bred on a tiny ledge east of Trad and below ‘Bracket’, which has become ‘Intermediate’. There are guillemots with razorbills up near the roof of Blackers Hole cave, but they are only really visible from the sea, by swimming, and I am uncertain whether they have successfully bred.

So the Blackers Hole guillemot population has increased from the 8 birds we counted of the cliff in 1957 to around the 95 I counted in June 2025. The long-loyal pair of razorbills have given rise to a colony of some 15 more pairs scattered along the cliff. For years, three pairs of shags - black, crested cormorants with a glorious green sheen - have nested at Blackers Hole, briefly increasing to 5 pairs before sinking to a single pair, which, for a decade or so, have raised three chicks each year.

Most of these birds are vulnerable to predators. Adult Kittiwakes are occasionally taken by peregrine falcons. We have also seen young falcons catching fledgling kittiwakes on the cliff and eating them beside the nest. Something is stealing their very young nestlings, too. That could well be ravens or carrion crows, both of which breed nearby and hunt in pairs, one diving down to scare the parent from the nest while the other moves in to seize the chicks. The cruel, light-eyed herring gulls are always ready to seize one of the neighbours’ young. Usually, the adult birds never leave their young unprotected but late this summer, when most guillemots had already gone, a couple remained with a large chick. Very briefly, they flew off together. I heard a scream and saw a gull carry off the chick and kill it on the sea. It then it dropped it, the chick sinking before it could pick it up again: a wasted life. Several years back, Trev saw a pair of ravens fly out of Blackers Hole, one carrying a chick They landed on the cliff to devour it. Recently, over several years, ravens ate most of the guillemot eggs from the Durlston colony. As a result, I presume, raven nests and young have been quietly put down and the Durlston guillemots are raising young again.

One almost extinct Purbeck auk, which, although settled nearby, never nested at Blackers Hole is the puffin. It was common along the Dorset coast and the Isle of Wight, but now only a couple of pairs survive a mile west of here, fading away as the other auks flourish. Elsewhere puffins suffer badly from rat predation. Agile beasts, it is probable that they are devouring the last remaining Purbeck young. When they go, puffins will be extinct along the whole south coast of England.

In the 19th century are common springtime ‘sport’ was to shoot sea birds from the cliff top or from boats. The corpses, if recovered, were used for fishing bait. Egg collecting was also a common hobby, which survived into the 1950s, our boyhood. Since the early 1970s, climbers have posed a problem to wildlife. They scared auks from a number of Purbeck colonies before being banned from vulnerable areas during the breeding season. Out of season, they still leave detritus along the cliff – ropes and clips – to mark their passing