15. Tanglin Cottage

14. Back Home In Purbeck 2020

July 30, 2020

16. Tanglin Cottage – The Garden

August 13, 2020T he house was one of a number of red brick Edwardian villas creeping steadily up Ulwell Road in the first decade of the 20th century. Edward VII reigned from 1901 to 1910: I think the Deeds dated it 1907. Ours was one of the smaller villas, north-facing and dressed in local cliffstone. One of its pretentions was a bell system for the servants; as long as they weren't very deaf, none ever could have been beyond calling distance. There was pretty coloured tilework on the hall floor and decorative glass in the front door. My father, carryng something into the house, used his elbow to prevent the door slamming on a brisk wind. The glass broke, slashing his elbow. That blood was an early memory; so was coming home to find a big, cuboid biscuit tin inside the door which opened to reveal a hoard of little cakes topped with icing, each with a glace cherry at its centre; left-overs from a family wedding, pure treasure in a time of post-war sugar rationing, which continued until the Coronation.

There was a garage next to the house but it was some years before my father filled it. The first car was an old, green Bradford Jowett van with, on its sides, 'Southern Electricity' thinly painted out and no windows in the back. We kids had little idea where we were bound until he opened the rear doors to let us out. There weren't any seats for us, either, only the covers of the rear wheels and assorted cushions chucked in before we set off. It spent much of its time unused, since he alone could drive and, serving in the army, was away for long periods of our youth folding up the map of Empire. There was India: Delhi, where he commanded young British soldiers keeping order at the time of the Indian National Army trials, certain those boys would run if there was a riot: it never came. Instead, there was religious conflict leading to Partition and eternal strife. Then he was in Palestine, where Zionist terrorists were bombing the British and ethnically-cleansing the land of its Arab inhabitants. British policy, faced with a flood of European refugees, was to keep Palestine united unless a democratic majority would agree to a Jewish state. But they handed the problem over to the United Nations, which decreed a still-unresolved partition and eternal strife. When my father applied for a compassionate home posting they sent him to Malaya for three years.

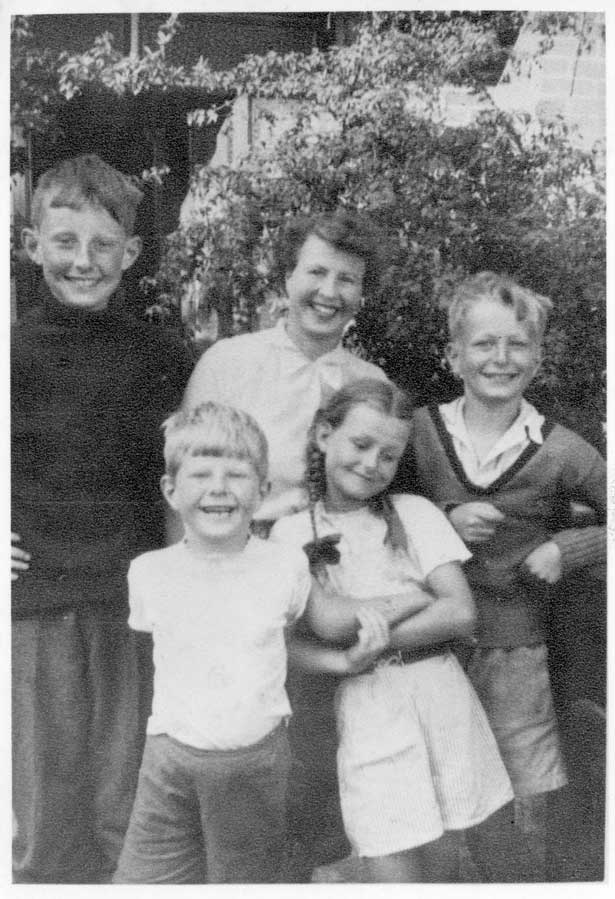

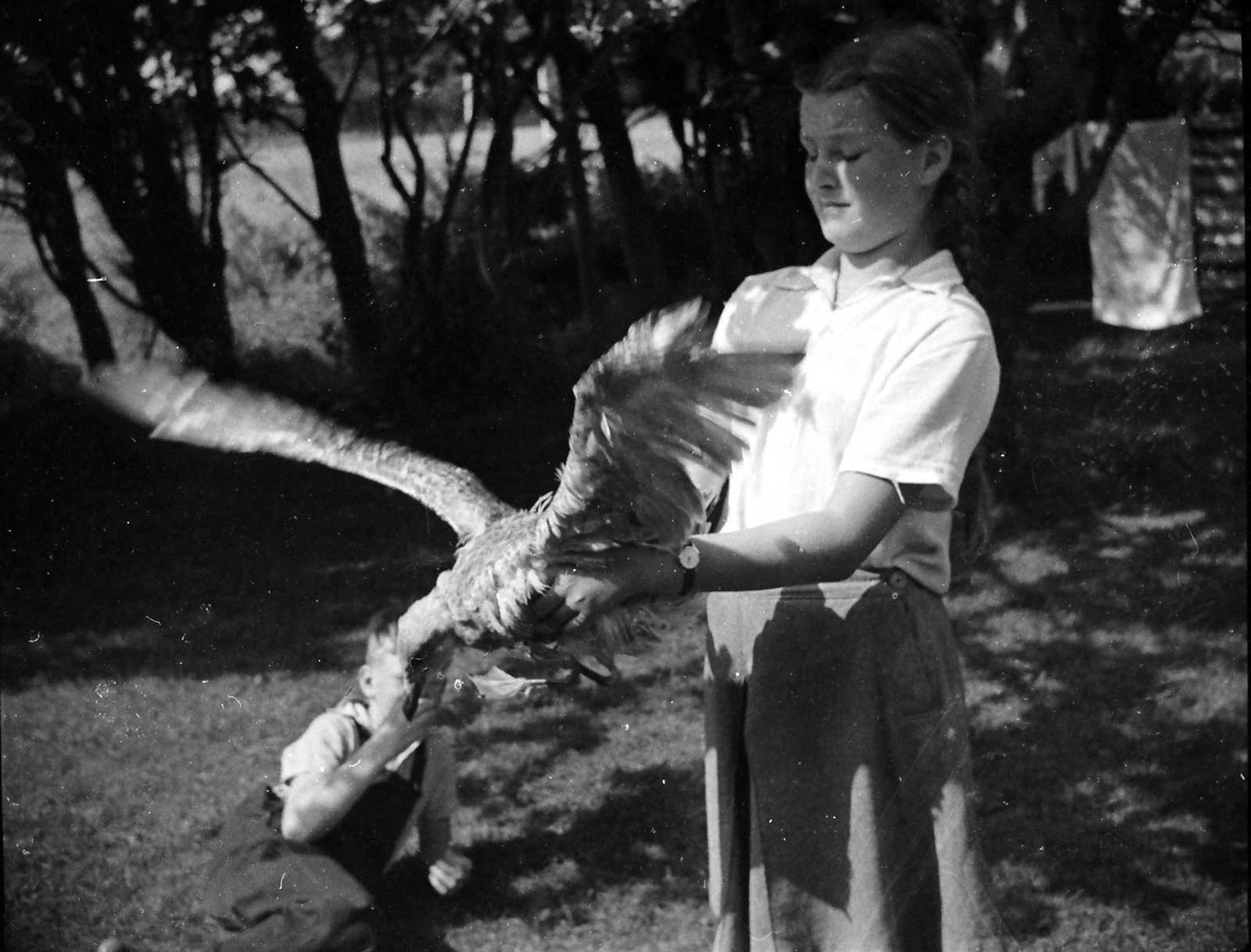

So the car stayed in the garage until, when Malaya became Malaysia, he finally came home and again could take the family out for weekend drives. I was rarely went with them, resenting his absences, preferring to spend free time with friends bird-watching. My mother suffered most from his spells abroad. She was intelligent, had aspirations but, at eighteen, with her father's death, had to help support her mother and siblings. In 1940, at 22, she was married and, faced with the shortened life expectancy of war, launched straight into a family of four. She must have thought wistfully of what might have been. But it was a happy marriage so, despite following his chosen career, my father, too, must have suffered the separations.

Tanglin Cottage, so we were told, took its name from the Bishop of Tanglin, in Singapore, who retired there. Its history was of no concern to us kids – it was home and, thanks to supportive parents, a happy one. When settling there, they took it forgranted that we would all end up at fee-paying schools. They could have travelled together, leaving us at boarding schools to be farmed out during holidays on often-reluctant relatives but that had been my mother's childhood: she was determined it wouldn't be ours! So we boys duly went to Hillcrest, a local 'prep school', 'preparatory' for a more respectable 'public' school, and Libby, to the local convent. But money was short. My father had been happy as a day boy at Bradford Grammar School. Then Anthony, the eldest, began to solve their problem by passing the 11+ exam into state-run Swanage Grammar School some 200m from the house. 11+? Kids entered secondary school aged over eleven; the exam decided which state school would take them. We all duly passed.

I think we were happy there. I certainly was. That school doled out a reasonable education and tolerated moderate individuality but the burdens of supervising a lively, growing family fell squarely on my mother's shoulders. During crises in his absence, the best she could do was to write to our father; by the time a reply arrived that trauma was long forgotten in the next. In spite of this, she gave us great freedom untrammelled by the risks implied. The awful obsessions of stranger-danger obsessions were yet to come, crippling the lives of so many later children. We learned by experience the dangers of life, that, then as now, adults were friendly and supportive as long as we didn't hassle them. Certain folk were to be avoided: we avoided them. The most pernicious sexual abuse of kids comes within the family or from people in authority, not from strangers. Luckily, as far as I know, none of them fancied us! We were lucky in our parents in many respects, particularly for that freedom and the welcome they gave our friends. As teenagers, each had the luxury of a separate room, only achieved by shifting me into a corrugated iron shed outside the back door. This was built, they said, for the chauffeur of a previous inhabitant. The bishop? My father, as limited as the rest of the family in 'Do-It-Yourself', improved on it, allowing me to choose the green, bamboo-patterned wall-paper. Once there, I could come and go as I pleased. The end result of our upbringing was security.