89. Living In A Box

88. Another Summer Reaches Its Height

August 1, 202490. Leaving Living In Boxes

October 3, 2024F rom 1970 onwards I lived largely between the homeland, Purbeck, and the Indian subcontinent, where, until the mid 1980s, my research was entirely unfunded. That sort of commuting is fine for the wealthy, fine for the propertied: I was neither. Based in desert Rajasthan, where the summer temperature annually reaches 50 C, it was for summer I chose to return. But Purbeck, pretty, seaside and little over two hours drive from London, is infected by the scourge of ‘second homes’ and summer rents are high. Be fair! I didn’t expect those like myself, single and nomadic by choice, to be prioritised. The worst of the problem falls on working folk with kids.

Returning, I needed a temporary home and work, sometimes as a waiter in Swanage’s largest hotel, which accommodated its staff. It was no holiday serving three meals a day, six days a week. There was little time off. The men were housed in Death Row, unofficial title for a row of basic first floor rooms overlooking a small road. Convenient, that – a friend would come to stay, parking beneath my window and climbing in from his car’s roof. If there was a need, I preferred working in a quarry for Trev, my best friend from school days. That’s where the caravanning started. Richard, another school friend, owned a caravan site. Caravans have a ‘best-before’ date, must be replaced after twenty years. They have little resale value and land for parking them is dear. Trev had bought a van to use as an office but he built one, rendering it redundant. Returning homeless from India in 1974, he offered me the use of it. That suited both, since I could work in the quarry during the day and his keep machinery running in the evening. That van was small, its exterior covered with aluminium sheeting, the interior lined with wood. At one end was a sleeping section, at the other, a living space with a couch either side. Set between wooden cupboards was a small stove, its chimney running up through a water tank. The centre housed a little lavatory cabinet and a gas cooker; gas also lit the lamps. Rainwater from the extensive work-shed roofs served for cooking and washing.

I kept a low profile. Few people passed that way but the track to a coastguard station at the end of a headland overlooked the quarry. The coastguards worked to a routine, so my lights were always out before 11.30, when the night shift took over. I was regular at the village pub, shopped and collected post from the little shop. Not all was calm. One February night, while at supper with friends a mile away, a strong wind got up and a flurry of snow became an easterly blizzard. The hosts pressed me to stay the night but, always one for drama, I waded home through the blinding snow. Already feeling a cold coming on, by morning I was feeling very sick.

Dawn broke on deep drifts, which had blocked the track. The wind died down, leaving the quarry overwhelmed by snow; this set some shed-roofs creaking under its weight. Luckily, health’n’safety hadn’t been invented, so, with a ladder and a shovel, I got up on the most threatened roof and set to clearing off the snow. It was some hours before the quarry work force arrived on foot to relieve me. Only one roof collapsed, that over the ‘Jenny Lind’, the stone-polishing machine, which I usually worked.

I was in and out of that van for several years, grew to rely on it, but came back one summer to find it gone. A storm had damaged it, setting one end flapping: Trev solved the problem with a lighted match. As the van blazed to its destruction, one of the workers just managed to drive his car clear. The van had contained some of my possessions: little remained save the steel frame and pretty stalagmites formed by some heat-proof dishes.

A few days later, dancing off my sorrows in Swanage’s night club, another school-fellow narrated his sorrows: his wife had left and, in the merchant navy, he was due on board in a few days. I offered to rent his house. That was the first of several more-solid buildings in my life; the last was a friend’s cottage, plagued with subsidence. She was working elsewhere, so I stayed there house-sitting through another excitement: the country still talks of the Great Storm of 1987. A solid stone cottage, the thundering wind woke me in the small hours, remembering washing left on the line. Forget it! Next morning was a scene of ruin. A fruit tree had blown from one garden into another. Branches were strewn everywhere. Anything movable had moved, flown even. All save my washing, which still hung listlessly on the line.

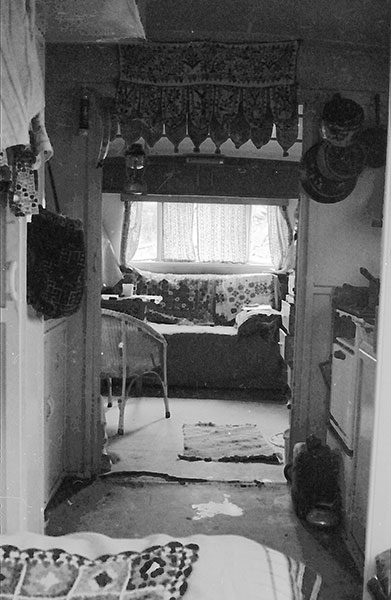

Back to India again to list buildings for the Indian National Trust for a pittance, I returned homeless in 1988. Trev put me up for a few days while I looked for somewhere else. Old School tie again! Bunny Farr had an idea: ‘Ask Mary if you can use her caravan.’ No harm in trying. She was out, but his sister, Judy, a tenant of hers, gave me directions to the van. ‘I wouldn’t let a dog live in it!’ but I was more tolerant than an English dog and besides, beggars can’t be choosers. Mary was agreeable and I moved in next day! She still kept livestock in that meadow. Lambs would wake me, chasing each other under the van and hitting their heads on the floor as they did so. Her curious Arab would look in through the open door and sweep the china off the draining board with his nose, then gallop off in terror. It was much like the quarry van, small, painted dark green with a wooden interior and two skylights in the roof. One addition was a partition folded down as a bed and the end section by the door served as a kitchen. Parked there by some divers, they had later abandoned it. Various waifs and strays had passed through: I was to be the last. But it wasn’t the first van in that meadow. A battered 1930s photo survives showing Mary’s mother, Hilda, and friends posed by a far more traditional model. Bunny remembered demolishing that one. But Judy had been fair. The van was barely habitable. Each year the roof’s leaks spread until a dribble opened up over the bed. That was the end. In 1994, Mary suggested I bring in another: ‘Paint it dark green!’