26. Starting With Ramgarh

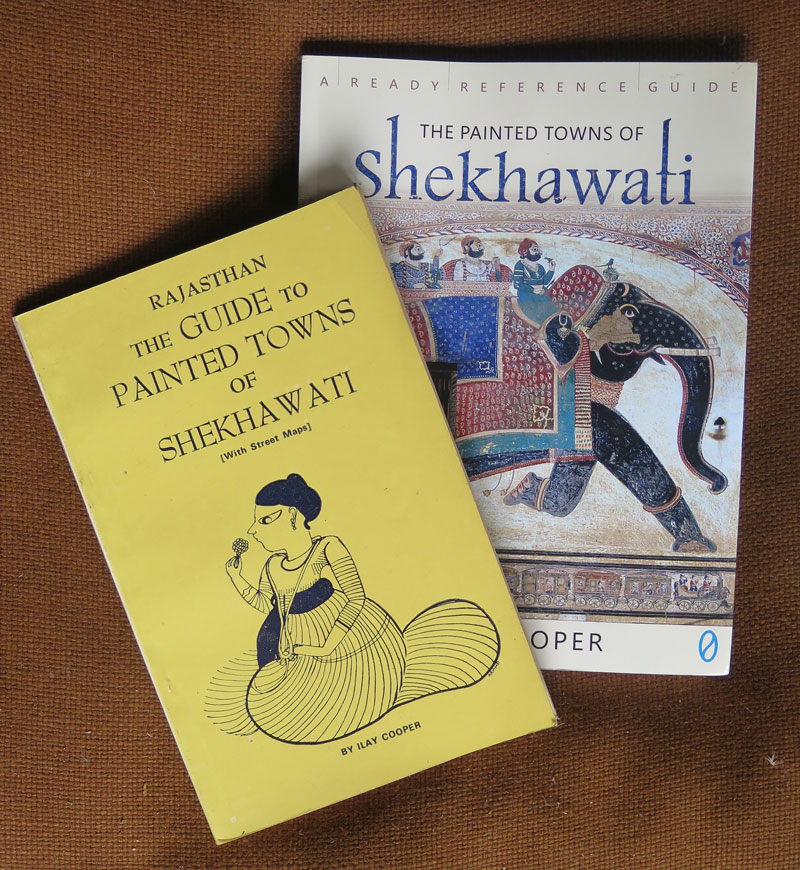

25. Into The Shekhawati Survey

October 15, 2020

27. Fatehpur – An Old Capital

October 29, 2020I t was something of a shock to come back early from Diu, under seemingly-enthusiastic pressure from INTACH, to find nothing ready for the survey and my funding slashed. I returned to Churu from Delhi with a new pocketful of promises. The seminar folk who had suggested the project were supportive, but they had no authority and, in 1985, sat at the other end of handwritten letters. The postal service was excellent; most letters between Churu and the UK took four days.

So I had the first, reduced payment but no film, no forms, no vehicle and no assistant. There was no certainty, either, that money spent on the project would be refunded. At INTACH Mr Jaissal had to field all my complaints. As a facilitator, he had no power to help us, could only carry out the commands from above. I was keen to start work; the people in charge seemed equally keen to be rid of me. The correspondence survives... mostly my unanswered letters. One letter is missing, the copy of INTACH's reply to the publishers, Penguin, which destroyed the chance of their taking my book. In fury, I had sent it to Sir Bernard Feilden without keeping a copy. Work began in an air of frustration.

I made my own mistakes, too; deciding to start in Ramgarh, the nearest important painted town, being one: it was 16km from Churu by crowded, irregular bus. We should have begun in Churu. Rabu suggested that, until his release by the education department, his younger brother, Ram Ratan, 'Munji', assist me. He was studying law, so we worked round his lectures. Every evening, I typed survey forms for the next day.

Ramgarh had a thriving antiques business. The dealer employed a tout, who waited at the bus-stand and invariably, hopefully sidled up to us. He got short shrift. Foreigners and Delhi folk were easily persuaded to buy. The dealers encouraged local folk to provide antiquities and enthusiastic tenants would offer fine carved woodwork and decorative mirrors torn from the havelis they rented. The dealers had several stores full of such treasures. The seminar quickly identified this trade as a major conservation problem.

Failing to acquire a street plan, we made one. Mapping Ramgarh is easy: inspired by early 18th century Jaipur, it was laid out on a grid plan based on an impressive east-west market intersected by a lesser north-south one. The other streets hung on that framework. Slightly off centre stands a sad apology for a fort. This was a merchants', not a warriors', town defended more by well wielded wealth than the sword. Our drawn plans would be approximate, using paced distances and building measurements. This posed an immediate problem: Munji was tall - 194 cm, I nearer 180 cm. His long-legged strides bore little relation to my more modest ones. Since Rabu and I, both of similar height, would be carrying out most of the survey we chose my pace as the standard.

Once sketched out, I made a fair copy of the map. Ramgarh architectural speciality was a fine array of terraced shops along its mainstreet and handsome domed chhatris (cenotaphs) beyond its gates. We started work outside the northern, Churu Gate with chhatris, mostly painted and dated, temples and wells. A few dharamshalas (inns) clustered inside the town's gates. Within the once-walled town were the havelis (merchant mansions) and shops with a scattering of temples and wells. We worked along the north market then the lesser streets of the northwest sector of town: any building notable for its structure, paintings or historic importance warranted a form.

Given the frustrations we suffered, Ramgarh is the most poorly-documented town of our survey. If Mr Jaissal had to suffer my problems with INTACH, Munji shared that burden through my constant tension and ill-temper coupled with ignorance of custom. After lunch, which his mother prepared for both, I expected to get straight back to work. Munji, quite able to hold his own, flatly refused to dispense with a siesta. At the end of each day, guilty at my irritability, I would buy us kulfi – ice cream. It was poor compensation. We completed Ramgarh in 3 ½ weeks; it proved to be Shekhawati's richest town, yielding 274 notable buildings. Then the forms and film finally arrived, leaving me to copy out all the forms, photograph each monument, then attach contact prints to each form.

On the last day of the survey, Munji swore never again visit Ramgarh with me. Fate intervened. Almost exactly ten years later, Munji, his father and I entered the town by car. He was coming to marry Rajni, a Ramgarh girl, and I was in his baraat – marriage party!

*

Regularly returning to Shekhawati, I look around the towns. With India's economy flourishing old gives way to new. Few of the buildings of the 19th century merchant boom will last more than 200 years. The local building materials are vulnerable to weather and decay. Rising damp, a major hazard, carries salts in solution up inside the walls where they crystallise fragmenting the fabric. Everywhere, footings decay eventually causing the structure to collapse. Buildings gradually disappear in drifts of windblown sand. Murals fade so that, at each Diwali when householders smarten the home, more are painted over. Some owners call in painters to cover their walls with new decorations but the result is poor.

Developers buy up and demolish empty havelis, replace them with modern concrete structures, often intended for shopping centres or businesses. Despite the accompanying illustration, chhatris are rarely destroyed: they merely die gradually of old age. Wells, still functioning to irrigate surrounding land when we surveyed them, are dry as the water table sinks, redundant, they are ripe for removal. A canal system has improved the water supply and people have become profligate. Wasted water floods desert streets, puddles house malarial mosquitoes and an unimaginable lake thus created north of Churu now attracts ducks, geese and even flamingoes. Ill-informed attempts at conservation can also disastrous. Large joharas, rainwater reservoirs, built at times of famine, now 'improved' no longer fill with each Monsoon downpour. Their beauty, water, will not return.