84. Persecutors And Protectors

83. Animal Life Usually Starts With Eggs

March 7, 2024

85. Coming By Real Estate

May 3, 2024T he previous blog started with a pair of sparrowhawk’s (shikra’s) eggs in a British nest, shortly before they were stolen to join a man’s egg collection. This blog also begins with a pair of eggs, but these are in India, a couple of scavenger vulture’s eggs in a nest made partly of hospital waste. It was easily accessible, situated on a chhatri, a memorial to a wealthy Hindu merchant, and the eggs are no less beautiful, but no one would think to collect them. There is a different approach to life.

Hinduism is not exclusively non-violent, vegetarian. Such a society could not survive in the real world. There are various branches of the faith, including those which are martial and non-vegetarian, but the Hindu attitude to living creatures is very different from that to which I grew up. They are generally are left in peace; even those that intrude into the human world are not routinely driven off or slain. It is common to enter an Indian room and find birds passing through it. House sparrows may nest behind hanging pictures or pigeons lay their eggs on a windowledge; no child would think of taking them. These invaders may become irritating neighbours, but not dangerous rivals. Builders may add little structures on the outer walls of houses in which parakeets or sparrows may nest, or leave recesses in the fabric for them.

It is not just birds. The sanctity of cattle is well-known. Rural families often provide a home to a cow, their hospitality returned by the provision of milk and its side-products, of dung to be used for plastering floors, or dried for fuel. The cow is no prisoner, wandering out into the street each day in search of food to supplement that which her hosts provide. There are suitable sources all around, hospitality is not confined to her own household. Each will make a daily circuit of the neighbourhood, standing outside each door in the knowledge that that, for the good of her soul, as she prepares the meals, the housewife will throw out the rougher vegetation, the peels, offcuts and leftovers. A favourite destination is the sabji mandi , the ‘green market’, focus of each Indian community, where the vegetables are sold. There, she thieves, slyly seizing a banana, an unguarded cabbage. Bulls, permanent street wanderers, are no less predatory; the sellers do their best to keep cattle at bay with a shout, a stick, but the delinquents know those threats are limited.

For the sick, unproductive or elderly cattle, there is the Gaoshala, a hostel funded by local wealthy folk as a refuge. There, they are fed and cared for, but retain the freedom to come and go at will. Meanwhile, pious folk will go out each morning to spread grain for wild birds. The late Mr Saraogi, a Jain draper in Churu, was one such. He used to carry a bucket of grain to spread on a bare patch of land beside a reservoir and opposite the local Gaoshala. Peacocks, parakeets, pigeons and sparrows awaited his arrival, flying down from the surrounding trees for their breakfast.

Most creatures have some sort of spiritual role in India and require respect. Take rats and mice as an example. In Britain, we grow up with a horror of those skin-tailed rodents, carriers of disease, armed with the teeth and the patience to gnaw through most obstacles and rob houses and barns . We put out poison and spring traps to kill them, keeping them at bay, but walk through Churu’s grain market, and you will see rats climbing hillocks of grain in the food shops. They are not encouraged, a waved stick drives them briefly away, but the shopkeepers don’t kill them. At night, they set live traps. All are full by morning and one of the shopkeeper’s family will put the traps in a bag and walk a couple of kilometres into the surrounding desert to release them. As each trap is opened, its prisoner leaps out and hops away across the sand, heading straight for the market. It arrives tired and hungry, ready to launch into the grain again. What is spiritual about a rat? It is the improbable vehicle of the elephant-headed god, Ganesh. There is even a rat temple at Deshnoke village sacred to the goddess, Karna Devi, patron of Bikaner, the kingdom of which Churu was once a part. It is a rodent paradise where the floor is richly spread with grain, where there are no sticks or traps.

Naturally, things have changed over the years. Science has intruded, spreading greater awareness of the negative aspects of many creatures. People are increasingly aware of the connection between mosquitoes and malaria. They accept the visit from the official who sprays houses to kill the insects. Like man himself, many animals spread disease. There are government officers with the task of eliminating the worst offenders. But there remain also those who wouldn’t countenance killing at any price – like the Jains, whose devotees wear a mask so that no life could be inhaled to its doom, who carry a whisk to sweep the ground before them so that no insect will succumb beneath their feet. But generally fellow creatures are protected by a widespread tolerance. Peacocks, protected by their sanctity – how could such a glorious bird not be holy? – wander through Rajasthani villages untouched. White egrets stay close to farm-workers, ever attentive in case they should disturb some edible beast. Deer and great Nilgai (a large, blue-grey antelope) feed through the sparse jungle around Churu, drinking from rainwater reservoirs and raiding green vegetable plots or wheat fields. Boys may be set to chase them off, but not to hurt them. On each lake or pond cranes, ducks and geese gather to feed, particularly during the winter, when they migrate from the north.

The exceptions to this gentle approach to animals include some Hindu castes, like the ruling martial Rajputs, or the ‘lower’ groups in the Hindu order of things, who hunt and eat flesh. In British times, the Jat Maharaja of Bharatpur would invite British guests to shooting parties hunt over the lakes in his land, which have now become one of India’s largest waterbird sanctuaries. Sometimes, the Viceroy came with his entourage and there remain lists of the enormous slaughter of wildfowl on these great shoots. The Maharaja, proud of his hospitality, put up memorials to the tally of death these V.I.Ps achieved.

Many coastal folk are fish-eaters and Bengali communities often escape censure by declaring that fish are actually vegetables. Some use sporting rifles, shotguns, while others, poorer folk, still use bows and arrows, or slings. Both groups of invaders, Muslims and Christians, of recent centuries were meat-eaters, slaughtering goats, sheep and also, more controversially, buffalo and cattle. In independent India both faiths have lost their power to the Hindu majority and meat-eating have become less acceptable. Customs have changed in those western lands, too, and tourists come to look, not to kill.

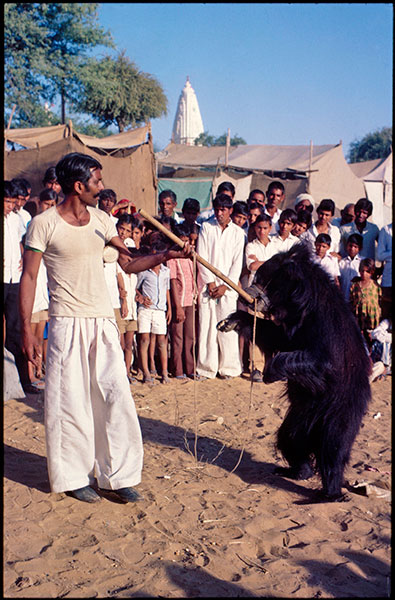

And yet, until recently, there remained some cruelties, animals imprisoned for entertainment. Since 1972, laws have acted against most of these entertainments. ‘Dancing bears’, sloth bears taken as cubs in the Himalayas, their teeth pulled out for safety, were once common throughout India. The practice continued long after the ban. I remember seeing a number of them in the 1980s on the touristic road from Agra to Fatehpur Sikri. putting a caste of masters out of work. Snake charmers, their cobras also victims of awful dentistry, are rare now. However, parakeets still tell fortunes and monkeys dance.