83. Animal Life Usually Starts With Eggs

82. A Last Glimpse Of Labels And More Birds

February 2, 2024

84. Persecutors And Protectors

April 4, 2024S o I ended last month by showing that, in Purbeck at least, global warming hasn’t caused guillemots to lay their eggs any earlier each year. Good conservatives, they stick to well-worn tradition. One of that blog’s pictures showed the bright turquoise wreckage of a guillemot’s egg. In 19th century Britain, such beauty of shape and colour exposed eggs to very negative predation: the fashion for egg collecting. Many birds already suffered for their spectacular appearance: a brooch made from a ‘lucky’ ptarmigan’s foot (unlucky for the ptarmigan), a delicate spray of egret plumes, colorful whole birds plumped on women’s hats. It was not just British ladies who exploited them. Elsewhere, both sexes used ornate feathers to enhance their glory. There were lots of birds around, empires to exploit them – peacocks, ostriches, amazing birds of paradise…

Let’s stick to eggs. In my generation, most country boys in Britain started an egg collection, competing for the rarest, using them as currency to swap with their fellows. Being summoned to the headmaster’s office had only one redeeming feature: an unimaginative man, author of an English grammar quite free of any attractive features, he displayed a confiscated guillemot egg on his desk. But there was a growing consciousness that such destruction was neither desirable nor sustainable. The Bird Protection Act of 1954 coincided with my first year at secondary school.

To start with, it was not a clear case of Them and Us. We all had our little egg treasuries, usually taking a single egg from each nest. Few of us hadn’t pinched an egg, pressed a flower, netted a butterfly. But, from my first year at secondary school the changing mood began to attract boys whose interest lay in the countryside to become more interested in looking, recording, than collecting. (Girls didn’t seem to be involved. They weren’t encouraged to wander the country. But that is for them to recall). One blurred photo shows the rookery behind my Swanage home, set in a line of tall, elegant elm trees. Along with most British elms, they were doomed to succumb to Dutch Elm Disease. They ran between a football field and a lovely bit of wild meadow. We climbed to some of those precarious nests (others were too scary to risk) and took an egg from each, piercing both ends to blow out the contents. Those rooks’ eggs were remarkably variable in colour and size.

Swanage Council, in its wisdom, tarmacked over that lovely little meadow with its patch of spring-fed marsh, orchids and chirpy stonechats, to make a new car park. Climbing the tall elms with the prospect falling onto that hard, black surface far below cured me of raiding the rookery. We still took Herring Gulls eggs but, in that era of post-war austerity, they were for food. It was only fair: gulls, yet to discover the wealth of Swanage’s fish and chip shops, (like monkeys at Indian holy places, they ruthlessly rob careless snackers), stole and ate the eggs of their sea-bird neighbours. The gulls also laid in late April, when the sea was still cold, some nesting in a favourite sea cave. I’d take eggs there, swimming in and carrying them away in the knotted sleeves of my shirt.

A gentle gang warfare existed between us and the boys who still collected eggs for a hobby. There were adult collectors, too. It was difficult not to admire the courage one man, who was notable for climbing the most inaccessible cliffs in search of rare eggs. Years later, when we were older and wiser, he and I talked about those days and I gave him a photo we, hidden in bushes, had taken of him climbing a tree to a sparrowhawk’s nest. (I took the photo of those eggs the previous day). He had a big collection and sold to other collectors, spoke of climbing down a chalk cliff reach a peregrine falcon’s nest. Alone, he tied a rope onto a fence post and lowered himself down. The cliff, some 50m high, slightly overhung the shingle beach below, which meant he had to swing in to reach the nest. Making it with difficulty, he took the eggs then had the challenging choice of climbing back up the rope or descending to the beach. The rope was 15m too short so that entailed a jump which he might survive, but the eggs wouldn’t. Eventually, he managed to struggle back to the top, or there might have been no story to tell! He showed me those same eggs. They retained their beautiful shape but the lovely, fresh colours had faded to a shadow.

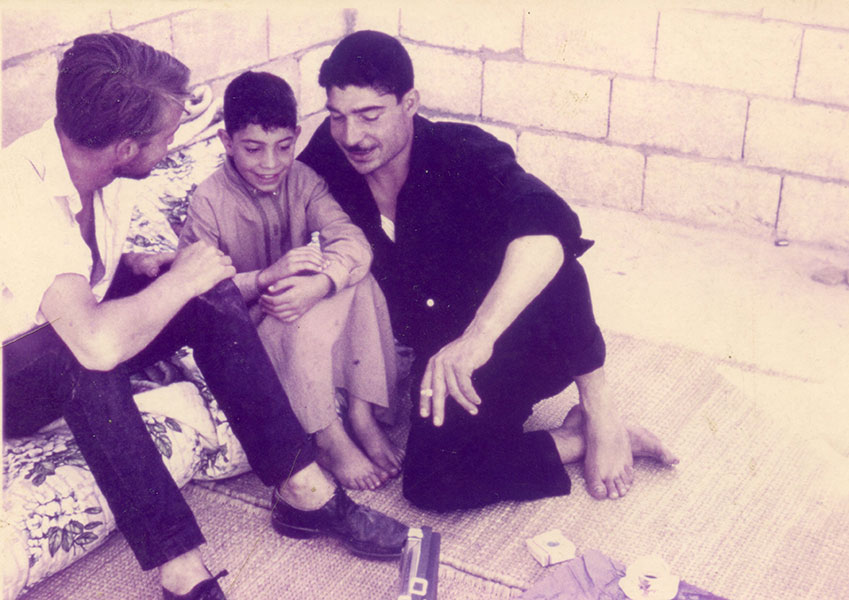

Egg collecting still goes on. A small, unfashionable group make birds’ eggs the trophies of their visits to the country. It has become a business, too. In past centuries, hunting with hawks was a widespread hobby of the elite. In England there was a gradation of folk according to their bird – lowest came a kestrel, a small hawk only good for catching mice and little birds, fit only for a knave. Rich folk in the Middle East keep the sport alive, training falcons to catch and bring back birds. I remember, in the 1970s, seeing goshawks being sold for falconry in Pakistan. Peregrine falcons are highly valued for hunting but they are rare in the Middle East. Gifted with deep pockets, falconers must look elsewhere for birds to train. British falcons were almost exterminated in the 1960s by agricultural insecticides. Small birds survived eating poisoned insects but, by eating many small birds, the falcons received a lethal dose. The poisons were banned and, today, British cliffs, trees and even city buildings provide nesting sites for many falcons. Climbers, their vehicles equipped with incubators, take their eggs and transport them to the Middle East, where the falcons are hatched and trained. A thriving smuggling industry!

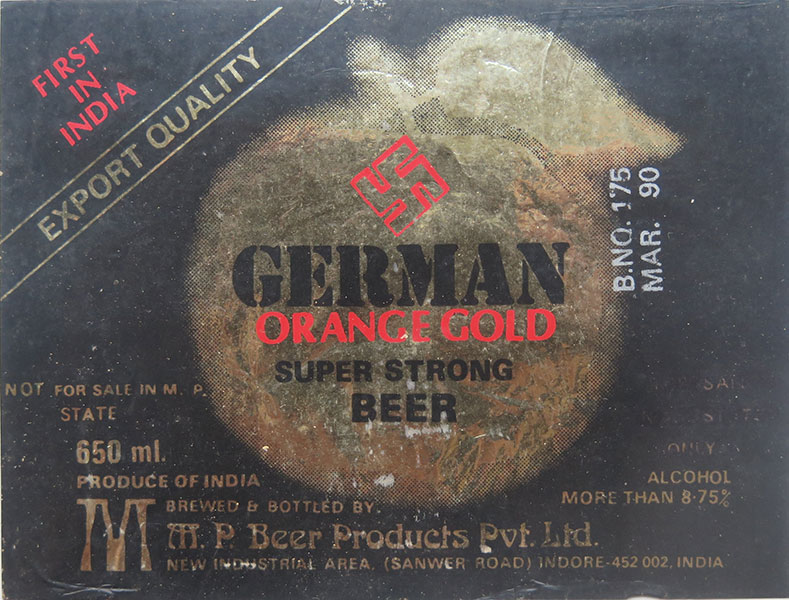

So an illicit trade in wild birds’ eggs survives in Britain. In India, no one seems to take birds’ eggs for any reason apart from food for a large non-vegetarian population. There are even ancient communities, such as the Rajasthani Bishnois (literally, 29s, the number of rules their guru laid down in the 15th century), which are dedicated to protecting wild creatures. Their rules include a ban on killing animals and on felling living trees.