57. The Odd British Inventions In Rajasthani Walls

56. The Passing British On Indian Walls

December 2, 2021

58. A Long Reign

February 10, 2022I t was no coincidence that an enormous British expansion across the globe coincided with the Industrial Revolution of the late 18th and 19th centuries. Manufacture had always been in the hands of individuals producing yarn, cloth, tools, utensils in their own households. Thinking artisans began to develop more efficient means of production, machines which multiplied the output of each individual worker. The output of a spinning wheel in the hands of a single ‘spinster’ was too low to feed the looms feeding an increasing demand for cloth the demand for cloth. Ingenuity led to innovation: the ‘spinning jenny’ resulted in an eightfold increase in o¬ne worker’s production of thread. It was an early step in that Revolution which comprised a continuous series of improvements for increasing yield. Water wheels powered spinning machines then were superseded by steam engines and manufacture shifted from cottages to large factories housing the new machines. The era of dark satanic mills saw no improved protection for a new urban labour force.

Through the 18th century India was the world’s largest textile centre but, as the 19th century advanced, mechanized spinning and weaving around Manchester and Glasgow shifted manufacture there. Raw cotton, source of the main textile material, had was imported from warmer, distant lands, above all from India. Thus a classic colonial economy developed: Britain imported raw cotton, which was then machine spun and woven – new methods of dyeing and printing completed the process and fine textiles flooded the Indian market. The local textile economy was destroyed by the competition.

Continual advances increased speed and size of output. Machinery required iron and steel. Concentration of production created new cities and improved communications were necessary to carry coal and iron to those manufacturing centres. Water transport inspired the construction of a network of canals. The steam engine gave rise to railways and steam-driven ships. Other equipment developed alongside the main industrial advances and steam-driven machinery led to mass production of goods. Enormous advances in wealth for an elite came at the cost of hideous conditions for British workers Mass production ‘cut the thumbs’ (a metaphor used at the time) off the Indian weavers, who were rendered redundant.

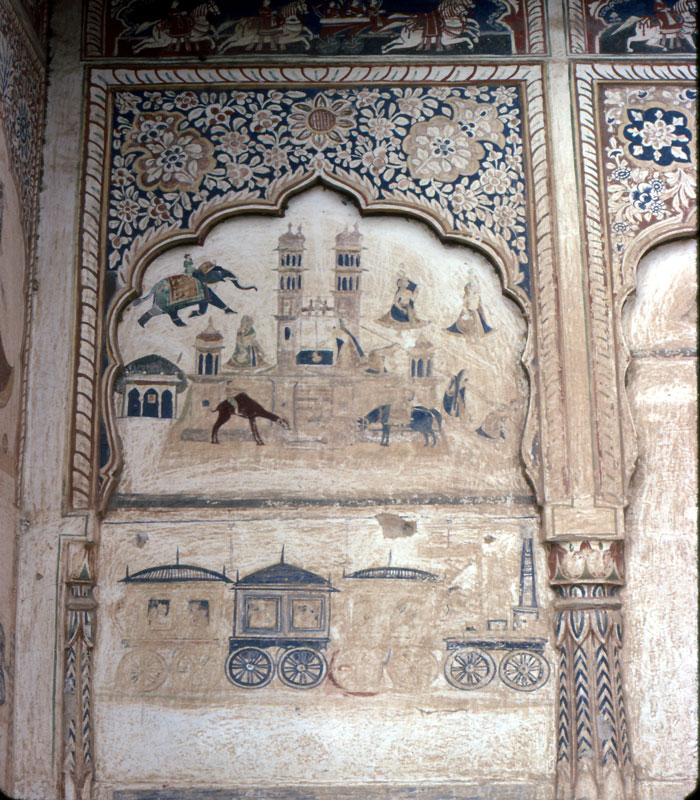

Indian and British merchants thrived on this colonial trade, handling raw cotton exports to Britain and the returning factory-made plain and printed textiles. They also exported opium to China in exchange for tea for the British market. Prosperity was accompanied by conspicuous building, which kept India’s mural painters busy. Looking around for subjects, they included the odd gizmos the foreigners introduced. A British surveyor often carried a camera lucida to cast an image onto paper where it could be accurately copied. The oppressive heat required a thermantidote, invented around 1830, a mobile hand-operated desert cooler. A servant was employed to rotate is fan and direct a cooling breeze through a wet screen onto sleeping travellers. The telescope, always carried by the British surveyors to examine distant buildings and landscape, was an early oddity to feature in murals alongside unfamiliar European chairs, tables and eating utensils. Later, they were joined by strange machines, known to be foreign since they were accompanied by men in hats. Some, I fail to grasp but mechanical pumps appear amongst the new equipment.

Foreign methods of transport were particularly striking. Steam power revolutionised travel within the huge country. A British steam launch was carried out to Calcutta on a sailing vessel in 1819 to be assembled and used on the Ganges. Things moved fast: by 1833 a regular paddle steamer service plied upriver from Calcutta, carrying grain and raw cotton downstream from the heartland of Ganges basin, and returning with manufacture goods, increasingly Manchester textiles, for a vast market. Images of these paddle steamers appeared at the top of every bill of lading issued to the merchants and many survive amongst ancient collections of business papers. Rajasthani painters probably never saw the ships, merely derived the likeness from those bills.

In the 1850s India’s first railways were constructed. The network spread rapidly to serve every town in the plains of India; paddle steamers, confined to river ports, soon became superfluous. A locomotive, manned by hatted Britishers, towing its string of trucks and carriages vied with a procession of uniformed soldiers as the most popular horizontal painted frieze on the walls of merchant mansions. The earliest in Shekhawati is a tall-funnelled locomotive decorating an 1872 memorial. There are copies of one particular scene at an English railway station as a train pulls in. Later train murals often have discreet sexual canoodling going on in one of the carriages. Sometimes the station staff, all wearing foreign hats, prepare for the arrival of a train, the stationmaster sounding his brass gong to announce an arrival or carrying a paraffin lantern. Men prepare the pump ready to refill the locomotive’s tank.

One mysterious scene of foreigners in a room around some sort of apparatus I decided must show some men distilling booze. The British were always associated with drink. Local illustrators were often vague about the images they copied. In the 1980s a brewer working with German collaboration labelled its bottle ‘German Beer’ and added a large swastika. A mistake: it was quickly replaced with a lotus!

In the early 1900s the first cars appear on the walls, often carrying ornately-clad foreign ladies driven by a uniformed chauffeur. Those cars evolve into streamlined classic vehicles bearing a local ruler or an important politician. Such cars still remain under dust covers in the stables of some Maharaja’s palace. Occasionally one passes on the open road. Then the painters turned to flight. In one picture, to explain the mechanics, the passengers blow into the hot air balloon (labelled ‘foreigner is flying’). There were Meccano-like planes, including a single triplane, most of them copied from prints.

In my town, Churu, is a single painting of a Scotsman in a kilt on a motorbike. Not far from it was a battleship attacked by biplanes – the sinking of the Bismarck? – but that building has been demolished. Foreign men and women cyclists appear occasionally. When I first cycled through Rajasthan people in one village pointed out a mural of a man of a cycle with his woman standing on the carrier, suggesting I was missing a trick. In another picture a boy stops to make a phone call, leaving his cycle parked nearby.

Few Shekhawati murals postdate Independence. As the British left, the merchant patrons moved to the cities to finance India’s own industrial revolution. However, when motorbiking along a rough rural track we noticed one memorable picture on the façade of a house, painted around 1955, showing the Bengali freedom fighter, Subash Chandra Bose; more striking was the woman tourist with her camera photographing of a doubtful local woman. A dog looks up at her admiringly.