56. The Passing British On Indian Walls

55. Dunshay Manor And Its Mystery Gateway

November 11, 2021

57. The Odd British Inventions In Rajasthani Walls

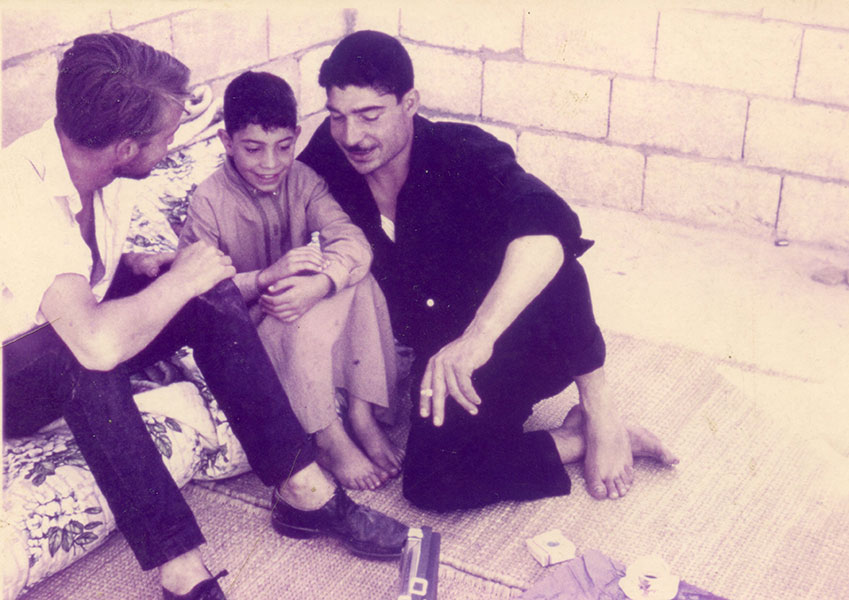

January 6, 2022W e’ve spent too long in England. Let’s gently return to India. When first looking at Shekhawati murals in 1972, the subjects I related to best were portrayals my compatriots. I was weak on Hindu deities and recognized few notable Indians apart from Gandhi and Nehru. Gradually the gods, rulers and heroes fell into place, learned from locals and the few captioned paintings: literacy was uncommon amongst the mason-painters.

My first painted havelis, in little Taranagar near the northern border of Rajasthan, offered the usual mixture of still mysterious Hindu religious figures, unknown heroes, birds and flowers; with them came two familiar British kings, their faces and reigns learned at school. They were Edward VII (ruling 1901-10) and his son, George V (1910-36). Each helped date the buildings they decorated. It was easy for the painters to find their likeness since they featured on postage stamps, coins, in newspapers, on ‘loyal’ prints and even on textile labels. It was tactful for the merchant patron to include them. Sometimes the elderly Queen Victoria (1837-1901) looked sternly down. There was even a single William IV, not readily recognizable for anyone without his caption, but that was elsewhere in Rajasthan.

Apart from the reigning monarch if identifiable European individuals were rare, generic ones were commonplace from the late 18th century onwards. They were set apart from local folk by their clothing. Instead of turbans, they wore hats, were clad in trousers and, mercenaries valued for their infantry skills, carried a musket. They were shown in battles or among turbaned troops.

The first European mercenary to appear on Shekhawati walls was probably Walter Reinhard, a German or Austrian who, defecting from an East India Company army, joined other deserters to serve local rulers. Faced with increasingly frail Mughal emperors, princely armies were contesting with each other for territory. Under the Nawab of Bengal, Reinhard supervised the slaughter sixty British prisoners in Patna before, In 1767, leading Bharatpur’s infantry into Rajasthan. As Samru the Frank, depicted in memorial chhatris to his opponents, he is the first European to be named in murals (see Blog 22). He is probably the mercenary shown in a 1776 Churu chhatri. His widow, Begum Samru, long outlived him as an important figure in her own right.

New rulers, the British were painted accompanied by a dog or, as known drinkers, holding a glass or a bottle. Unlike Indian notables, they sat in elegant chairs. Most had uniforms, worn also by the vast majority of local troops in a British-officered Indian Army. It took a long time to identify two British officers painted in a recessed panel of an 1830s haveli in Ramgarh. Only when writing Rajasthan: Exploring Painted Shekhawati did I realize they were Col. Lockett and Lieut. Boileau, along with Rabu and I, the principal protagonists in that book. They camped at Ramgarh in 1831. Lockett wears a lubada (a quilted coat) and uses glasses to consult one of his reference books. Boileau, younger and slimmer, is smart in scarlet. His line died out, but his brother’s Boileau descendant lives in Dorset and helped in my research. In front of their tent, the artist laid the table with those mysterious utensils Europeans required for meals. Aware of the picture’s historic importance, I took many photographs: soon afterwards it was painted over with mauve acrylic!

In one temple painting some uniformed soldiers man a battery of cannon which faces scarlet troops apparently lying down. The artist had a clear idea of his subjects: they often puzzle a modern observer. I got there in the end. The temple was built in 1860, shortly after the Mutiny/First War of Independence. This shows the retribution, when British forces captured many rebellious (or often innocent) Indian troops and shot them off the mouths of cannon.

By the late 19th century mass-produced imported prints had become a rich source of inspiration. When decorating one haveli room, in 1898, the merchant patron must have suggested sex and royals as suitable décor. The very accurate royalty, including an elderly Queen Victoria and Princess Alexandra, were either traced or copied using a grid. Nearby, the painter could happily execute freehand some erotic panels: these ladies modestly ignore them. Appropriate beside Queen Victoria is Lakshmi, Goddess of Wealth. Women are frequently painted from this period onward, often shown in cars, occasionally on bicycles.

The artists were generous in satire which, topical when painted, has since lost its meaning. One faded panel combines a smartly-clad gentleman, a rabbit and a woman. Only recently, sorting photographs, did I look at this more carefully - and understand: it is the Abdication crisis of 1936. The man is Edward VIII, the woman Mrs Simpson for whom he renounced the throne. The third party is no rabbit but a donkey, which, in India, often represents lust.

Increasingly powerful through the 19th century, the British faded after WW I. The empire was weakening. A Briton had founded the Indian Congress Party with the aim of promoting limited self-government. Soon all limits were too many. It became increasingly clear that self-government was bound to progress beyond such limitations. Indian political figures, achieving prominence and power, began to appear on the walls, reflecting the progress towards freedom.

A 1930s picture in a haveli courtyard shows Bharat Mata (Mother India) standing on a map of the subcontinent beside George V, king emperor. He hands her a rolled document: this must be Freedom! It was only his son, George VI, who actually granted that freedom. Around them are famous Freedom Fighters and a knot of hatted British officials. The humour hasn’t vanished: above the door to a stairway – jina – is a portrait of Jinnah, the Muslim League leader.

There is a final painting relating to end of that imperial escapade. ‘Quit India!’ had become the popular anti-British slogan. The picture shows Mother India, tricolor in hand, standing in triumph on the Indian map. In the bottom left-hand corner, a meek little Briton, still wearing his hat and bent under the weight of a knapsack, is finally quitting India.