64. Fatehpur Sikri And Agra- Mughal Murals

63. Delhi – Then Back To The Road

July 14, 202265. To Agra’s Mughal Sights, Then Southwards

September 1, 2022I n 1992, my Shekhawati mural research yielded funding for two winters’ work in Pakistan. There, Dr Ebba Koch had identified murals uncovered from whitewash in Lahore Fort’s Kala Burj (Black Bastion) as from Jahangir’s reign (1605-27), the finest era of Mughal painting. She described their similarity to contemporary murals, also emerged from whitewash, in buildings at Rambagh, a garden in Agra. I discover more such paintings in Lahore Fort, including Christian saints in the Sehdari (‘Three Doors’), and drew attention to angelic outlines in Kala Burj, yet to be uncovered from whitewash.

Back in India, I visited Rambagh, where two decaying pavilions overlook the river, Jamuna. Supported by the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI) and a ladder, I examined murals in the pavilions. This was no dead monument but, with AIDS rife, a popular rendezvous for naughty boys in search of gay romance. Some tried to entice me from my ladder. Today, Rambagh is less lively. Lahore Fort and those pavilions bore similar motifs executed in much the same palette. In both, segments of the qalib kari (geometrically moulded) ceiling held flowers and realistic birds, each copied from a dead specimen. Jahangir, loving painting, the natural world and alcohol, could gaze up at familiar species, perhaps even correcting some. Both sites had Persia-derived angels, one at Rambagh carrying a peacock. Around Lahore’s dome battled two magical simurghs, fierce, ragged-tailed mythical birds, wanderers from China via Persia. In Rambagh, a simurgh seized a duck. Body-less, winged cherubs from the European baroque had flown in, too, faintly decorating Rambagh’s ceiling and masonry brackets, cheerfully circling Lahore’s dome.

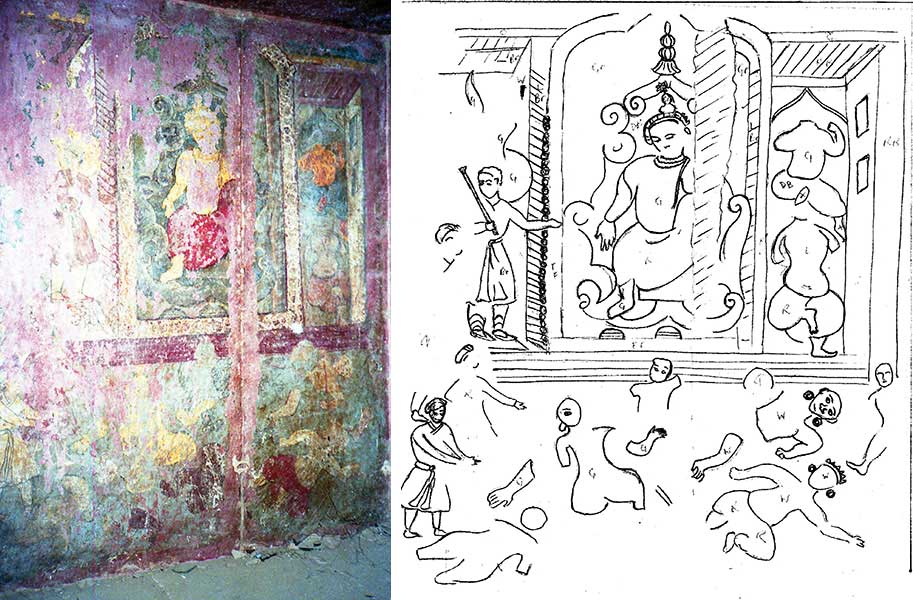

There were differences: Rambagh had deer, fat-tailed sheep, cranes at a pond and, long-overlooked, a seated hunter aiming his musket. In Jahangir’s religiously-tolerant court, Jesuits arrived, dreaming of conversion, but their welcome derived from the realistic holy pictures they carried: the medium, not the message! Both buildings bear uncomfortable Christian saints. Those in the Sehdari, including a dramatic Gregory the Great, were initially identified as British: I soon realized they, too, were Jahangir’s work, carefully stencilled from those holy pictures. (A portrait sketch of a Mughal prince amongst them in 1993 has since disappeared) Meanwhile, in Rambagh’s inset panels, much abused with graffiti, were more, freer copies from Europe: St Antony, another bearded figure – Jesus? - and, framed between two swagged curtains, a woman reading a letter. These panels were pecked over with a punch (see picture) so that a layer of covering plaster would adhere.

Alien figures are not unexpected on Mughal walls. Jahangir’s artists borrowed from everywhere; surprised foreigners at his court described such pictures. Manucci, an Italian settled in 17th century India, wrote of Christian murals in Akbar’s tomb near Agra, even mentioning their fate. The emperor Aurangzeb (1658-1707), painfully holy, actively destroyed figurative art and un-Islamic shrines. Hearing of his plans to whitewash those paintings, Manucci hurried to see them, describing a crucifix, the Virgin Mary and St Ignatius. Aurangzeb would also have provided the whitewash for Lahore and Rambagh, effectively preserving the images he was so keen to erase. Smashing two great masonry beasts guarding Sikri’s Elephant Gate was probably also his work. Who but an emperor had the power or inclination to destroy them? Cycling into Fatehpur Sikri in 1973, I mention neither the elephants nor the murals. The overwhelming impression of the place is the magnificent red sandstone architecture built in the spirit of Akbar, wise ruler of a diverse land, as a synthesis of Muslim and Hindu styles. Later, I discovered Edmund Smith’s work. In 1881, he made a careful study of the traces of murals remaining there, delegating artists to copy them. Their careful drawings illustrate his writing and inspired me to revisit the town.

There, in the Sunahra Makan (‘Golden House’), a panel shows a flute-playing woman, another, two Persian angels identified by Christians as an Annunciation. The outer walls bear many faint busy figures, buildings, gardens, flowers, animals and cartouches containing Persian poetry. There is even a dancing Ganesh (now decapitated) and a carved Ram with Hanuman. One vignette, high on its north wall, shows two 7 cm long Siberian cranes pursued by a falcon: the artist has even added a pupil to each bird’s eye! Occasional errors slip into those 19th century copies; here, a draughtsman misinterpreted a man on a light horse as a tent!

The damage here is more obliteration than neglect. Some point at Jat folk washing gold from the pictures, others blame the British, but why? If Aurangzeb destroyed those elephants, he would have obliterated figurative pictures. Relief carvings of animals elsewhere in the town have heads carefully chiseled away, human figures so neatly demolished that their forms remain clear. The murals in Akbar’s Khwabgah (‘House of Dreams’) seem to tell a story. Smith’s team copied these, too, with the occasional mistake. Fairly well-preserved panels survive either side of each dark window recess. There, my torch revealed the wreckage of a flaming golden nimbus about the head of the tale’s hero, a beardless youth in red. The ever-helpful Robert Skelton, examining my drawings, suggested this could be Hamza, hero of the Persian Hamzanama epic beloved by Akbar. He indicated an Akbar-period Hamzanama painting in the Victoria & Albert collection showing inverted idols, a miracle at the birth of the prophet, Mohammad. A picture in a Khwabgah’s north window recess is reminiscent: that nimbus-ed youth in red gestures towards an array of smashed idols, surely a similar miracle.

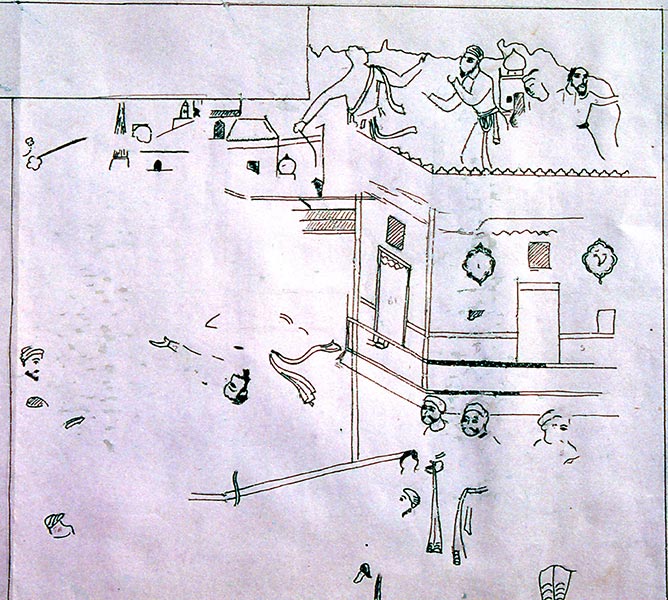

More visible in the Khwabgah, thus purposefully damaged, are large painted dado panels with erased captions. Smith’s team drew these, too, overlooking the dramatic focus of one picture: men point at something, but there is nothing there; then I noticed a faint but desperate falling man (see drawing). In some panels there are ships: Hamza sailed to Sri Lanka. Akbar commissioned several richly-illustrated versions of the Hamzanama. The surviving paintings are glorious. Those in the V & A were found in a Kashmiri shop, some of them blocking windows. Sadly, many of the faces have been roughly erased. Oh, for a view of those newly-painted buildings. Surely, making a definitive record of Fatehpur Sikri murals and interpreting them would be an ideal challenge for some observant, enthusiastic student’s PhD.