65. To Agra’s Mughal Sights, Then Southwards

64. Fatehpur Sikri And Agra- Mughal Murals

August 4, 2022

66. Gwalior’s Fort Then South Into Bundelkund

October 6, 2022L eaving Fatehpur Sikri in the late afternoon, I cycled east towards Agra city past acres of sweet-scented, yellow mustard flowers. Were there dancing bears that day? They certainly became a feature of that road in later years, enticing tourists to stop and part with cash. Those bears didn’t have much to dance about: as captive cubs, their teeth had been hammered out and they were trained as slaves of their masters. Forgetting the agony of crude dentistry, they saw their man only as provider of food.

Cycling through Agra’s Shahgunj sector, I asked for a dharamshala. A small Sikh led me through narrow streets, past mobs of noisy kids, but the place was closed. The children followed my retreat, plucking at my cycle, clothes and bag; visions of the film ‘Suddenly Last Summer’, a scene of small boys overwhelming the man who preyed on them. Two unusually tall young men came to the rescue. One, Arun, stopped where the alley became almost too tight for the bike to pass, and, like Horatius at the bridge, held back the hoard. Soon, we had the refuge of his house, which was built around a courtyard. His elder brother showed me how doors, now sealed, had connected the neighbouring houses. The other boy, Tapan, was Bengali and talked of the Bengali films currently so popular in London.

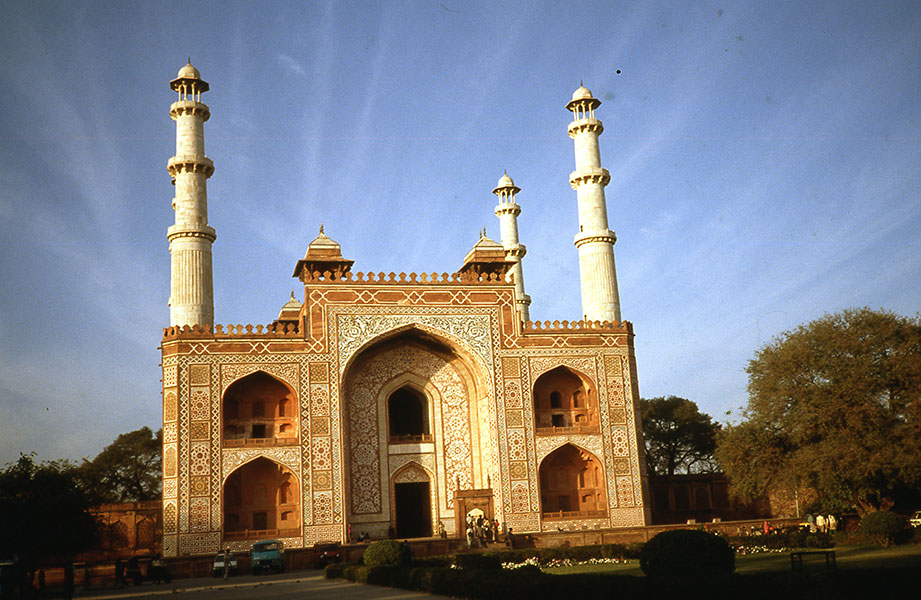

Arun’s family, British Punjabis from Kenya, had moved to Agra when he was only five. His grandfather had served in the British Indian Army and talked of pre-destruction Palestine, Iraq and Egypt. They duly fed me and put me up. Next morning, Arun, his finals approaching, went to College after indicating the road to Sikandra and Akbar’s tomb. The vast, main gateway, a marquetry of white marble in red sandstone, once contained murals, some with Christian subjects, but the iconoclast Aurangzeb had them whitewashed over. It opens into a large garden surrounding the mausoleum. One expects a dome, but there is none, only layers of horizontality and a flurry of little cupolas. The grave lies at the end of a dark, descending passage which suddenly gives into a high chamber above a marble box tomb. Far above it, a small window lets in a faint beam, illuminating a patch of wall to create a most impressive space. In the topmost storey, under open sky and surrounded by marble latticework, is an intricately-carved marble ‘coffin’. But Akbar is nowhere. Rebellious Jats, vandalising the tomb in the 18th century, scattered his bones.

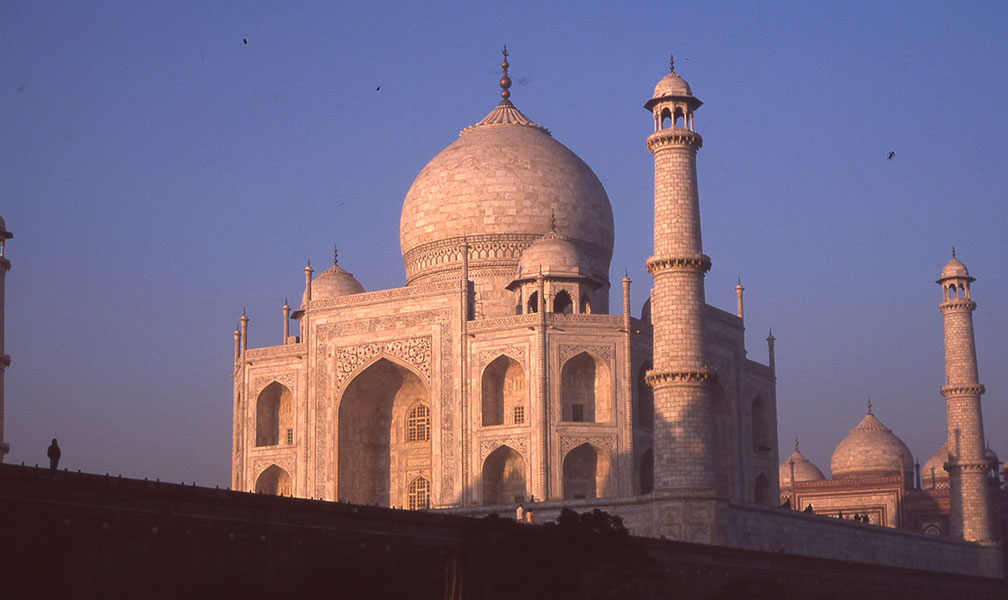

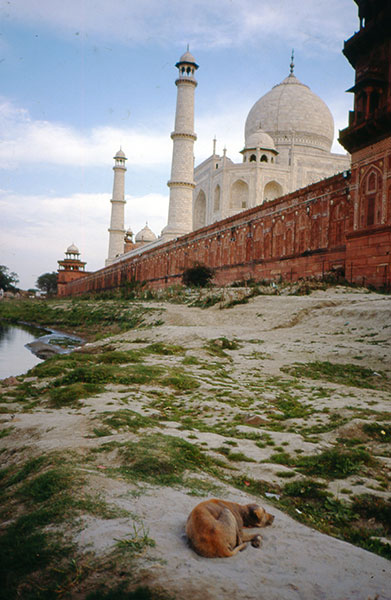

Arun, Tapan and I lunched together then cycled to the Taj, where Tapan knew one of the gatekeepers, so we got in free. If you await a lustrous essay on love in white marble, forget it! They chose a place to sit on the lawn to smoke while watching a young foreign couple kissing as the cricket commentary burbled away on a transistor. It was only later that we entered the building, where the black chevron pattern is a challenge to all young men. Most can only touch the four lowest zigzags without jumping. With a jump, I reached 5 ½ but Arun, taller and with basketball training, made 6 ½. Afterwards, the Taj done, we returned to the same spot, the same couple and the cricket. On the way back, Tapan led a diversion by a village of prostitutes just outside the city. Many were quite young and attractive girls, some clad in saucy western clothes; others, primly sari-ed, sat or stood in front of houses set back from the road. Arun had not been there before, was reluctant about the whole enterprise. Both admitted to being virgins. We stopped for tea and samosas. Tapan was depressed; with his family in Delhi, he felt lonely, aimless. He would like to wander as I could. We white westerners were rich, free; a few months’ work financed a warm, wandering winter.

Next morning, Arun pointed out the road south. We would meet again, many years later. He had settled with an Indian family in London and, suffering from M.E., wrote to me. I went to visit him, but we had little in common, save for that brief encounter. On the road I was accompanied by one or other cyclist with the same conversation. For each, I was a novelty; for me, they were not. At my first tea halt the elderly patron, who was washing a puppy, offered a dark boy of about 14 to take with me. The boy seemed disappointed when I continued alone. Past Dholpur the road descended to bridge the green Chambal river and looking down on people washing clothes. It was flanked on either side by a strange, deeply-gullied landscape, renowned for its bandit hideouts. The ruins of a fort guarded the crossing and a squashed hyena, the sole roadkill, decorated the tarmac.

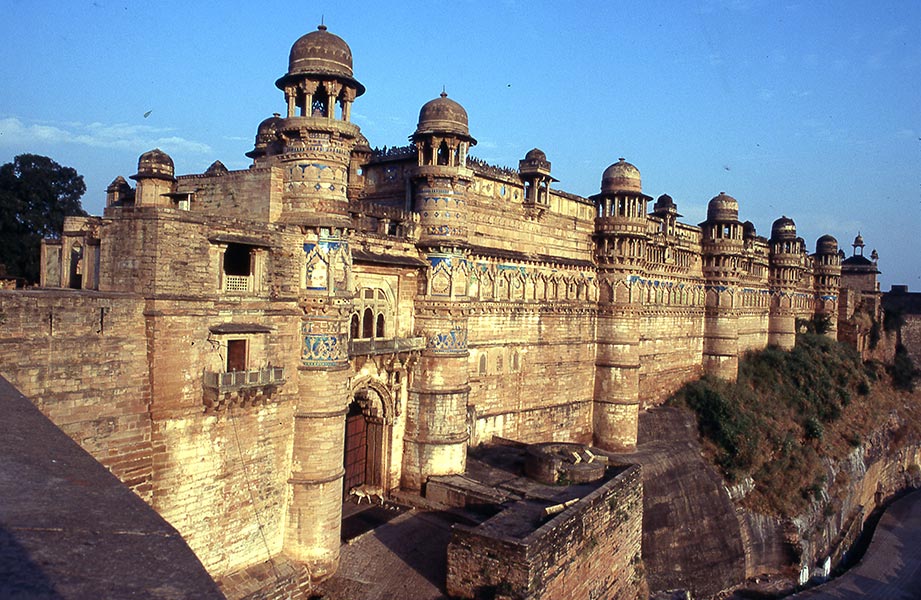

Beyond, at several irrigation canals men bathed. I was tempted to join them but that would cause too much of a stir. Instead, I lunched on tiny boiled eggs alongside peas fried in ghee. A line of 30 empty bullock carts, a rarity today, clattered by a copse of date palms. It was dusk when the road passed below Gwalior Fort on its long hill. There was a rough dharamshala near the station. While bathing, I examined my blistered arse, victim of 120 km on a new saddle, before sleeping with the bike safely in the room. I soon woke to a musical tinging sound. It stopped as I sat up, started again as sleep returned.

The mystery was short-lived. A large rat walked along the bed in front of my face. There was a basket on the bike’s handlebars and in it biscuits. The rats were climbing up over the spokes, plucking them musically, but they could never reach them; the bike was on a stand, so the wheel simply rotated. The sods were getting in by a drain through the wall. I tried blocking it with a Hindi primer. They soon shifted that. Stuffed the hole with newspaper and listened to the rustle as they attacked it but, too tired for a long vigil, I eventually drifted away till morning.