68. Orchha And Its Painted Temple

67. Bundelkhand And Datia

November 3, 2022

69. A Moving Experience

January 5, 2023J hansi, with its small but historically important hilltop fort and the heroic rani’s palace, did not keep me long. I cycled east then left the Khajuraho road southwards, stopping to admire the Betwa river where it widened into a pool amongst rounded boulders. In the little town of Orchha they directed me to a rough dharamshala. A woman chowkidar with ferocious teeth greeted me, smiling, and charged next to nothing for a basic room: no electricity, no windows, no bed hence no bed bugs and a door that locked. All I needed!

Orchha proved a wise diversion. The living village adjoined dead, deserted palaces and temples. Once capital of a small princely state flourishing in the early 17th century, in 1783, the Raja vacated it for Tikamgarh, 50 miles south. They say the growing British presence in nearby Jhansi was too close for comfort, but Orchha survived, some of its palaces and temples still being redecorated and royal cenotaphs built, into the 19th century.

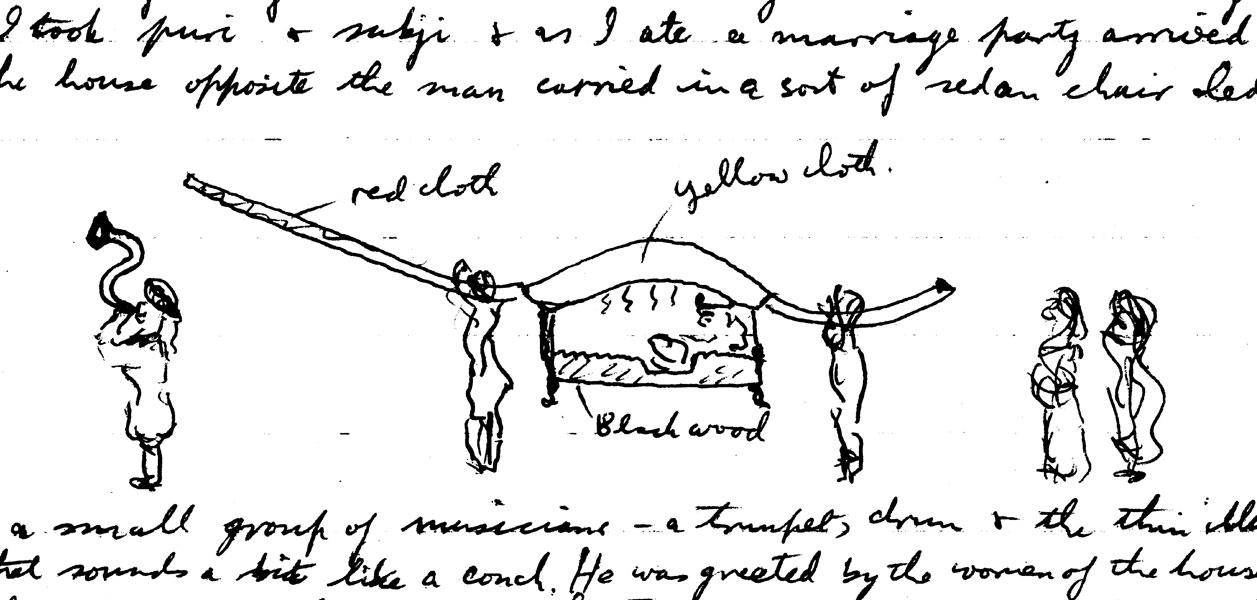

The abandoned walled town lies in a loop of the blue-green Betwa River. The roof of the Jahangir Mahal overlooks dry, sparse jungle from which abandoned temples rise. The village boasted a tea house offering aloo sabji and roti. A baraat – marriage party - led by musicians with trumpets, drums and a serpentine horn sounding like a conch, arrived at the bride’s house opposite. The groom stepped from his palki to be greeted by the women of the house. Even then a palki, an ornate sedan chair, was a rare sight, as was, in so small a place, a 100re note. I managed to change it, then had a shave, sitting cross-legged in front of the barber. His cut-throat razor was not exactly sharp but he added a head massage to the deal.

Rejuvenated, I walked down to the temple-like royal cenotaphs beside the river. They were empty save for silvery, black-faced langurs. The sky was dark, threatening; cloudy green water glided around smooth granite boulders. Fish were rising and further upstream were noisy rapids. A skein of Brahminy duck flew over.

Back at the tea house, dusk falling, I joined an advocate and four of his friends playing whist-like kotpiece. My partner and I lost. We all moved into a room above a gateway, drank deshi – hooch - and talked of sex. The advocate, smiling, said ‘This is a poor country’, implying it was lucky since there were many poor available to satisfy the better-off. He offered to cater for my every desire. If the prospect was attractive, the implied exploitation jarred. I refused. The moon rose, silhouetting the palaces and lighting up the facades of big temples; by the grey light I returned to the river to sit smoking and admiring its reflection in the fast-flowing water then, back in the room, wrote by candlelight.

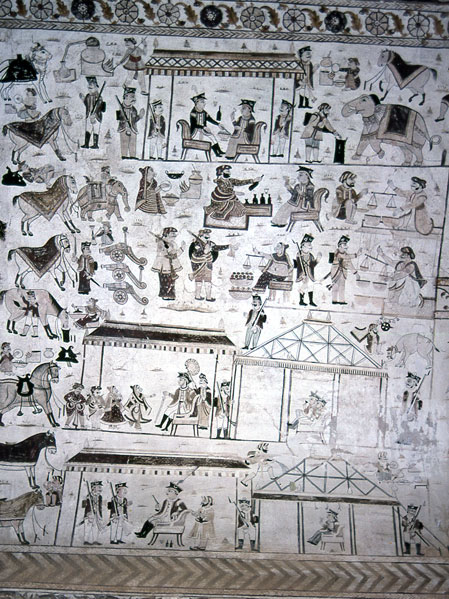

Waking to fudge-like burfi with milk and a bathe in the river, I wandered through the scrub, passing scarlet-flowered roira trees from ruin to ruin towards the hilltop Lakshminarayan Temple, expecting another dead, derelict building. Raised in 1618 on the square plan of most Bundelkand palaces, it was built around a courtyard with a domed cupola at each corner, uncharacteristically, its entrance through a corner. The vaulted ceilings were rich in 19th century murals, more than making up for the temple’s tidy dereliction. Most were of lively hunting and religious scenes, the latter showing incarnations of Vishnu, including Ramayana episodes leading to ten-armed Ravan’s battle against Ram’s heroic army, or tales of Krishna. Interspersed were dancers, musicians, folk tales, wrestlers and floral designs. Generally, the colours had faded but the ink outlines remained as clear, monochrome drawings. Shadier parts of the vaulted ceiling, however, retained the original colours.

Pictures in the northeast cloister portray uniformed British and Indian Company soldiers. Details of their uniform - the occasional bicorne hat or the low shako - and the painters’ style suggest they were painted around 1840. Were they inspired by an 1829 visit to Orchha by the Commander in Chief, Lord Combermere? That would certainly have been a big event in a little state. Among some nice dado panels, incised, scraperboard-like, through thick maroon paint, are two British officers vandalised by graffiti. Is one of them Lord Combermere?

Unusual among the pictures are those of British camp life. Smartly uniformed officers sit in tents drinking. Perhaps the officer watching a ‘nautch’, a performance of girls dancing, could be Combermere. At the top of that sector a man is distilling drink while, in the middle of the picture, a shopkeeper is selling a bottle to a soldier. Several men and a woman are busy making and cooking round chapattis and a brass lota by them would hold melted ghee to brush onto each. A number of shopkeepers sell goods to passers-by; does that include balls of the intoxicant, bhang? In the lower left a woman sits at a hand-mill grinding wheat into flour. A groom tends horses and a mahout gives water to the elephant tasked to carry the seniormost officer.

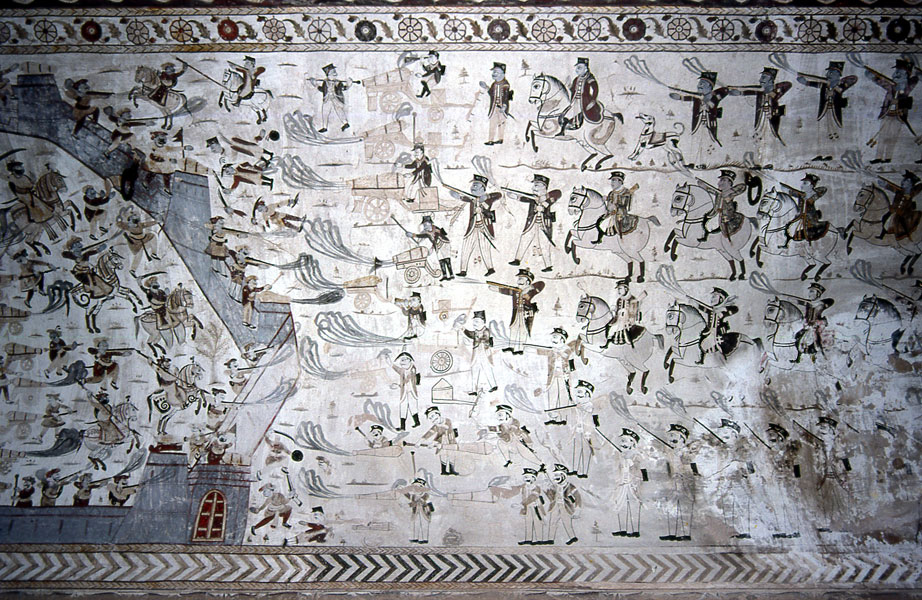

Cavalry and infantry leaving the camp proceed to the left, preparing for battle as they go. The horsemen carry muskets, aim them as they approach the action, then fire. A plume of smoke rises from each muzzle. The infantry also march out, bayonets fixed. By the time they, too, aim their muskets, the bayonets are gone. They reach a rank of cannon, some being loaded, the rest also firing. The attack is directed at an Indian-manned fort. Dead and maimed British soldiers lie beneath the walls.

Descriptions of this battle scene attribute it to the rising against the British. Not only does it appear stylistically earlier but the painter would know that the 1857 war the British called ‘the Mutiny’ was largely between uniformed Indian troops and uniformed Britons. Here, the defending army is clad in Indian style. This suggests another battle, perhaps the storm of Bharatpur in January 1826. And who was in charge at Bharatpur? Lord Combermere! They were a disreputable crowd. The British were supposed to be evicting a usurper and installing the true Child Raja. That they did, but only after sharing out the captured Treasury and royal jewels amongst themselves. Lord Combermere took 600,000 rupees, some £50,000 – generous booty in 1826!

Leaving Lakshminarayan’s temple, I avoided a pi-dog bitch growling aggressively from a nearby room - she must have pups – to return by an enormous, deserted Chaturbhuj temple. There, salvaged from elsewhere, vermilion-painted Ganesh figures presided. Climbing its tower gave me a view across jungle interspersed with ruins to distant Jhansi fort.