67. Bundelkhand And Datia

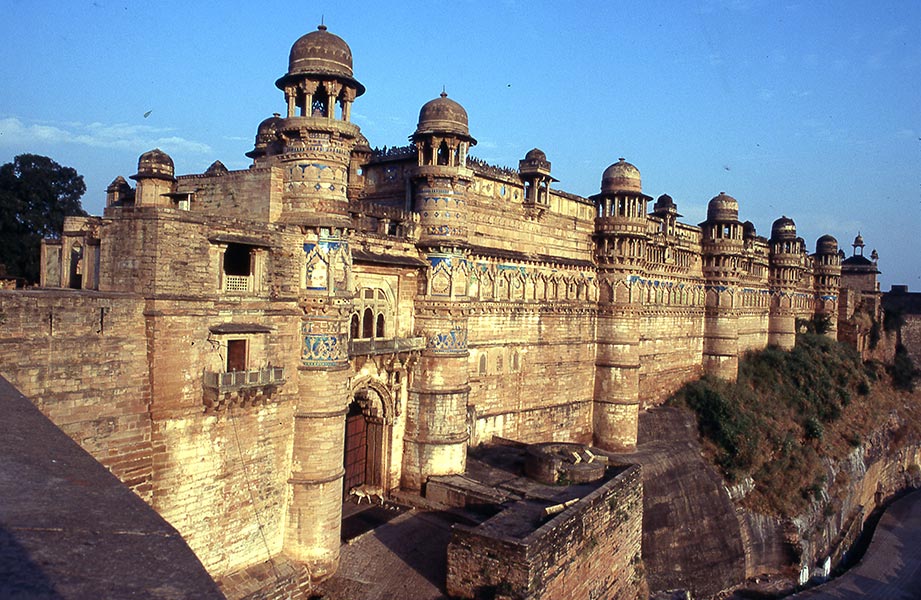

66. Gwalior’s Fort Then South Into Bundelkund

October 6, 2022

68. Orchha And Its Painted Temple

December 9, 2022B undelkhand describes a large tract of land once ruled by Rajputs of the Bundela clan south and east of Gwalior. Datia, Jhansi and Orchha, along my route, were amongst its major princely capitals. From Datia, Shiv and I cycled south to Kerri village, overtaking groups of people heading there on foot, in tongas or in bullock carts with bells ringing. The women sang. Kerri was crowded for its annual fair in honour of the local goddess where everyone was drawn to little stalls selling religious books, flowers and holy pictures. Musicians played, occasionally interrupted by the blast of a conch.

After buying sweets, we continued towards Unao, passing a track which, according to Shiv, led to an Ashoka pillar. When I expressed interest, he said it was too rough for cycles. Such pillars, set up by emperor Ashoka in the 3rd century BC, are important landmarks in India. Checking recently, there wasn’t one near Datia. We visited a couple of schools, then a temple dedicated to Balaji, which was disappointing but, Shiv assured me, very holy. Steps descended to a clear little river where children swam and women washed their clothes. We bathed, too, before starting back. By now we had been joined by Sitaram, son of a local farmer. At his farm, we drank from the well, ate birr (wild berries) and green chenna (chickpeas), before relaxing beside a field of young wheat. It was all rather homely.

Back in Datia, Shiv borrowed my bike while I went to a tea stall. There, the headmaster of Unao primary school appeared, mourning a recently-dead friend and very much the worse for bhang. His one-time classmate joined us, a strange, intelligent man, unshaven, poorly dressed and currently working as assistant stationmaster. His English was fluent, punctuated by quotes, delivered at a speed which made it hard to follow. He opposed the struggle for material things, caste, religious strife, politics and took unpaid leave whenever he felt inclined. Radiating honesty, folk judged him half-crazy.

Shiv returned with some fellow students, Vijay, Anil and Tafajul. They questioned and I answered, then realized they found my English very difficult. A moonlit night, Shiv suggested I shared the room he rented from Anil’s family so we all moved there to talk and sing. Anil wanted to know about sex life in England. Tafajul sang sad songs. The girl he loved girl didn’t love him, had refused to meet him. A handsome fellow like him shouldn’t give up hope. He and Vijay, a dark Rajput with strange, slanted eyes, proved the best singers. I sang ‘Chalte, Chalte…’, from the currently hit film, ‘Pakeezah’ and some English songs then failed to teach Vijay ‘Greensleeves’. He never mastered the first line. When the party broke up, I laid out my sleeping bag on Shiv’s floor. Next morning, I agreed to stay another day, then returned to the dharamshala to bathe. A plain-clothes CID man with no English came to inspect my passport followed by an English-speaking officer, who also perused the passport. Vijay and Anil arrived as I washed clothes, inviting me to lunch at Anil’s. There, his sisters, one speaking good English, produced rice, dal, aloo sabji, good pickles and roti. The younger girl served us, whilst her sister and mother sat, talking. It was a pleasant, relaxed atmosphere.

Outside the town’s gate, we stopped at Shiv’s school, where he had the kids sitting outside in rows in the shade of the wall. His class should be sixty 5 to 11 year-olds, but many are irregular. A tough job…but a challenge. I felt quite enthusiastic just looking at those lively kids. If I had the time… Later, at the local degree college English lecturers talked of Hardy, politics and white ‘colonialism by consent’, a concept which was never really explained. Afterwards, an objectionable little fellow took us around the fort. He was very polite, just objectionable! Some trophy heads decorated one room, including a hippo, which, so locals say, came from a great bird that terrorised the area, eating whole cows. Anil said they were wrong; that bird had been killed by the British and taken to England. I was taken to the post-death feast of an old man, who had died 13 days previously, and was served aubergine sabji, puris, sweets and tapioca on leaf plates and bowls. Shiv brought more food, including rasgullas and little sweets of maize flour, deep fried like jelabis.

In the market Shiv had a shave (with a cut-throat razor, then costing about a penny) before we continued to the secondary school, me perched on the cross-bar while Anil peddled. A full moon illuminated a concert in the school grounds where a pretty girl of around 12 performed a kathak dance quite well. The principal announced that Datia’s ex-maharani had presented the college 51rs as reward for her dancing. Some boys reckoned the money was intended for the girl but the principal purloined it. She was followed by other students singing bhajans and ghazals. One girl played the sitar and Tafajul presented her with a ‘gold’ medal he had. I was soon bored and cold, moreover everyone had deserted me. Some boys came up, one speaking good English. He wanted to go to England, saying that in India one’s future must be bought. I disagreed, said he should change his country not leave it. He was practical, I, a prig! Datia was beautiful under the moonlight, its cottages sparkling white, the palace black and clear. Shiv appeared, also cold, and we went back to sleep.

The voice of the man who showed us round the fort woke me, talking at the top of his voice. I feigned sleep, hoping he would go. He didn’t! Shiv brought sabji and roti then took me out of the town gate and showed me the road towards Jhansi and I set off again. It was soon hot and I remembered my shorts still lay in Shiv’s room however, full of energy after a few days rest, I reached Jhansi without stopping. I had a Jhansi connection. My grandparents started their married life there. Avoiding the cantonment, where they had a bungalow in 1916, I put up in a rough dharamshala before climbing to the fort overlooking the town. To Indians, Jhansi means Lakshmi Bai, hero of the 1857 war. They say she escaped by leaping on horseback from the fort wall – no mean feat – only to die fighting the British near Gwalior. Shiv wrote to me many years later. He was studying in Moscow and wanted American blue jeans. Then in India and low on cash, I replied but didn’t send the jeans. They were a famous form of currency in Soviet days.