73. Poison And The Holy Land

72. A Purbeck Diversion, Then Back To Saucy Khajuraho

April 6, 2023

74. The Demise Of Beasts & Humans

June 1, 2023A ccidentally casting aside a scrap of blotting paper, I forgot it bore two tabs of LSD. It was that era. Did one of India’s many cattle, which have a liking for paper, pass an unusual day as result? So to poison: Purbeck spring, time to plant rows of seeds for another year. Onions alone survive from last summer. In the hardware shop, the seed display, purveying rebirth, gives way to Death. Each packet bears bright flowers coupled with pictures of the horrid beast that brought their destruction. Gardeners hate slugs, but must they be reduced to foaming, writhing wrecks? Poison, with all its side-effects, is a crude answer. Another mixture aims at ants. Why ants? Another slaughters woodlice. Slays beetles: I thought they ate slugs. Birds eat the corpses: tasty titbits bringing lethal stomach pains. Kill flies! Kill wasps (probably works for bees, honey)! Kill moths! Kill insects! Packets marked ‘Kill the Bugs’ seem to work for everything. The result is a garden emptied of all the smaller wildlife on which the larger wildlife subsist. Before building my house, ecologists came round and, for a fee, checked for certain forms of life that might be threatened by the project. The two favourites are newts and bats. No one asked what poisons lay in my shed, waiting to destroy the very creatures these beasts eat. Kill the bugs and you bugger the newts and bats. The few killed accidentally during building are nothing compared with those dying from the generous broadcast of poisons over the land or starved by the dearth of things to eat.

I once bought a green container of ‘Slug Death’, thinking green meant something, read its green credentials. The manufacturer protected himself against all manner of accidental death through consuming their mixture. Dogs and cats won’t get any benefit from the stuff. You can soon rid the garden of butterflies – not just cabbage whites. Yes, I hate slugs, but it is a personal vendetta which can be solved personally. Kill slugs on your plants, or put out saucers of beer for them, inebriated, to drown in. But don’t waft spray like an ignorant, unthinking angel of death. Those poisons should be banned. And what of weeds? Who reduces plants to weed status? Keep spraying, then: such a pretty sight, plants contorted in death rigors. Again, it is a personal struggle. Why not strim the plants that so offend, giving yourself a choice of what must die.

There, my rant is over. We can all go back to destroying the planet in our own small, sweet ways. Back to the road:

After tea with the old man, having spent 80p repairing the bike’s free-wheel (It was oddly stiff), I left Badausa. From a roadside tea house I glimpsed a woman, dressed in bridal finery, carried past in a palki, a claustrophobic box, by four men. They turned off along a rough track to a village. The horsedrawn carts and tongas here were arranged for one person in majesty, such was the space under the howdah-like shelter. An elegant hawk hovered low over a field: back grey, underside white, black wing feathers; a black-shouldered kite. Climbing laboriously up a hill, I anticipated the easy descent to follow: it never came. This was a plateau. It was a struggle but, as dusk fell, I reached Shankargarh. Having barely eaten all day, I ate no more here, unenthused by cheap sabji and roti. They said there was a dharamshala: there wasn’t. The stationmaster offered his third-class waiting room.

In the rough, dusty main street of town the only breakfast on offer was jelabis with hot milk. Drinking and eat everything, my stomach was mildly upset. Unfamiliar germs lurk on every side. Allahabad lay 50 km ahead but, tiring fast, I made it. Beyond the Jamuna river, blue-green, deep and wide, crossed by an iron, Birmingham-made bridge came a massive urban snarl-up. Midday, it was hard to progress amongst the rickshaws and tongas in the strange city. Exhausted, I stopped for boiled eggs, then, failing at various hotels and dharamshalas, ended on a charpoy in a common room. Cycling was becoming hot, sweating profusely from village to village, which created blisters on my arse from coarse, damp jeans. Continue to sacred Benares, but beyond – why? As far as Gaya, more from duty than desire? Having slept through the afternoon, a nearby Chinese restaurant offered a massive, affordable meal.

Outside into warm evening chaos and noise, rickshaw bells, horns, the harsh voices of hotel boys, bells and hooves of the tongas. When strong enough to support the interminable stares and questions asked across a gap that could engulf the universe, I was content. I’ll soon need cash. Where should Amrit send it? Must decide before leaving Allahabad.

A student asked: ‘Why have you come here?’. To a weak reply, he continued: ‘You mean you came here for nothing?’ An older man, whom he was offering hopes of employment, gave the little bastard exaggerated respect, urban terycot pants against his own rural khadi. Sent to fetch paan, he returned empty-hand and was sent further. But the question remained: Why am I here, anyhow? I need stability; I was nearly thirty. This life hadn’t been wasted – but enough: a new chapter, a steady job: make this the last trip. I often said that. Outside, it rained hard.

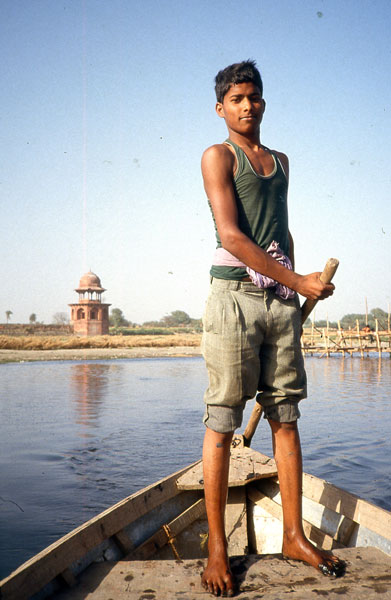

Across flat mud banks to the Sangam, confluence of brown Ganga with blue Jamuna, I swam on the Ganga side. The early crowds thinned. Nearby stood a pilgrim group led by an authoritative youth with exaggerated gestures. A line of boats was moored across the confluence, save where the current was too strong. There, rowing boats shuttled. Every twelve years, for the Kambh Mela, millions of pilgrims cover this expanse of flatness. The bank is of clean sand, little metre-high cliffs slowly eaten back by a deflected current. Bright flags flew, some with strange pious motifs. Were the differing colours of the rivers discernable? I took a boat across. They were: the Ganga water was undeniably, unpretentiously brown, the Jamuna, a translucent green. The boatman wanted an exorbitant 15rs. Such easy robbery! To prove it, I took the oars, rowed out, then all the way back. (To be fair, having rowed since childhood, I am good at it!) Amazed, he charged nothing. The water has a strange chemical smell – chlorine? - still perceptible later, beneath a tree with cay and a Charminar cigarette. So many flies!

After a breakfast and the morning paper, I quit Allahabad. The freewheel finally packed up; serious, an 8rs repair. Midday approached before I finally crossed the Ganga bridge. A vast elephant, face painted red, waded slowly across the river. The water rose, reached its belly then, gradually shallowing, it paddled out the far side. The going was easy through those green, fertile plains. Sweetly scented trees lined the Grand Trunk Road – mango blossom? I think not. Siris? Two sky-clad Jains approached, naked men walking towards the holy city, bearing only fly-whisks to save insects from their dreadful tread. As dusk darkened, at a crossroads well before Benares, a friendly man put my bike in his courtyard and brought out a cot. I was soon asleep.

*