71. Where Was I? Orchha And Onward

70. Shekhawati Updated In My Final Home

March 2, 2023

72. A Purbeck Diversion, Then Back To Saucy Khajuraho

April 6, 2023…B ut before picking up where I left off, a brief diversion. Spring approaches. Purbeck’s cliff birds are staking their claims. Snow drops are fading, primroses flowering. Now for an early puffin. I touched on that in the blog in 2021 when, after many years, I pushed back the date of the first puffin from 1st March to 28th February. The squabbling guillemots are already visiting their ledges and smart little razorbills bob and snog on the sea. This year, at midday on 15th February, a puffin sat amongst them: the record was smashed again, but by a greater margin. But back fifty years to India….

The days at Orchha were high points on that cycle ride. The people were friendly, the buildings impressive, if derelict and a little eating-place in the market both cheap and passable. Orchha was fated to become a tourist attraction, but that was a long way ahead. In the heat of the day, I escaped to the cool, clear winding river, drying off on a great, rounded boulder emerging from the torrent. A flock of Brahminy duck decorated the shore and terrapins rose, phallic, from the river’s surface to glance, then sink again. The best spot was beside a row of temple-like royal chhatris, where rajas were cremated even after the capital shifted. A good place to leave the earth, peaceful.

An old man with a small group of cattle came to cadge a beedi, ask of my caste, my village. At night I read by a series of small candles, each slightly illuminating an hour. The dharamshala room was basic, sleeping bag on a concrete floor, but sleep came easily.

The second morning passed in palaces. The Jahangir Mahal had been built for that emperor’s use. I doubt he ever saw it. A pity; with his eye for the natural world and its depiction, he would have liked the place. As prince Selim, he rebelled against his father, the great Akbar. Orchha’s heir had sided with him, assassinated Akbar’s historian, Abu’l Fazl, who opposed Selim’s accession. His massive tomes, a Domesday book, an account of the reign sit, rarely disturbed, on my bookshelf, best part of a wheel-barrow load then I moved in.

Little seemed to have happened to that building after Jahangir’s passing. It was one of three such palaces here, following a square model typical of Bundelkand, two-storey wings enclosing a square courtyard. A domed room tops each corner and is central to each side. The vaulted rooms are small, the few surviving murals faded and battered. From the roof, beyond citadel walls, stretches a far expanse of rolling, dry jungle punctuated scarlet-flowering roira trees and glimpses of river. Eastwards, a stable block entered by high arches once accommodated laden camels and elephants.

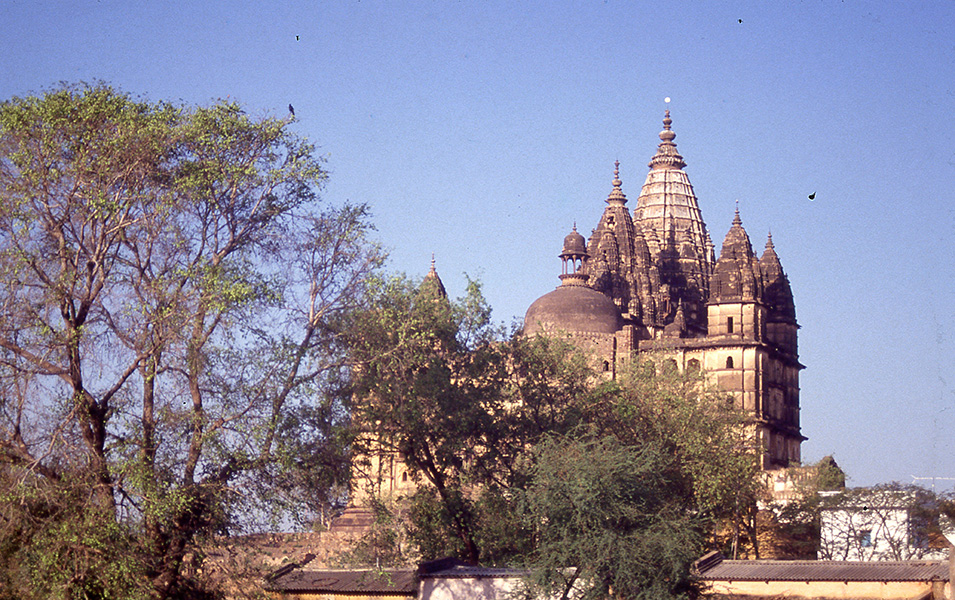

The second palace, Raj Mahal, once housing the ruler, lying to the southwest, looked out over the little village, no doubt much bigger now. Beyond it towers the Chaturbhuj temple, a veritable cathedral, which rarely performed its function, its morning bells reminiscent of an English village church. When they brought the god here, he was carried first to Ram Mandir, where, making it impossible to proceed further, he remains enshrined.

The Raj Mahal is richly painted, redecorated over the years, for it was a living palace until the ruler shifted to Tikamgarh. Some of the murals may be original but the brightest, liveliest are the mid 19th century work of the same team who painted the Lakshminarayan temple but here a dark interior has preserved the colours. Attached to its outer wall is an audience hall retaining early, Mughal-inspired paintings of cypresses and highly-individual hunting falcons. The Ram Mandir, west of the bazaar and beyond the walls and oldest of the three, is perhaps prototype for this architectural form. If built as a palace, the deity’s refusal to budge made it a temple, now painted a remarkable pink.

That evening there were no puris to go with the vegetable curry. Instead, they provided a vermicelli-like snack made of lentil flour, which served as a good substitute. The urge to move on came after a type of nightmare then quite frequent, but now almost forgotten: someone had broken in, stolen my rucksack. I woke, but into another dream, paralysed by the unseen presence of the intruder. The terror of helplessness of woke me again, this time into the realm of reality. The room was empty but for the bike and an untidy jumble of possessions. There was another, preferable, recurring dream in those days: I could fly – no waving arms nonsense – just jump and walk through air, looking down to wonder why other people didn’t do the same; it was so easy….

Next morning, at nine, crossing the Betwa river by the concrete bridge my grandfather never saw, I headed for Khajuraho, a major tourist venue in Central India. Over 150km to the southeast, it was more than a day’s ride but, before the cycling became tedious, a bus stopped: they chucked the bike up on the roof and carried me, free, to Chatarpur, stopping to provide samosas and tea. Few days passed without someone displaying such generosity. When they handed down the bike only fifty km remained. They passed fast.

Just before Khajuraho, a boy carrying a baby appeared, cycling in the opposite direction. Astonished by the foreigner on a bike, he lost control, knocked into me and fell off. Thankfully, neither he nor the baby was hurt, but we were both shocked. The clearest surviving memory was of a young man by the roadside, who looked at me with burning hatred.

By 5pm, I was settled in a tent – the cheapest accommodation. The entrepreneur who, in founding Hotel Chandela, launched Khajuraho as a tourist destination was a Churu man. Later, he tried to do the same at home, naming Churu ‘The Shangri-La of the Eighties’. He attempted to employ me in the project, even providing khaki shirt and trousers for the role. He claimed the surrounding golden sand dunes would be enough attraction: I suggested the quirky wall-paintings might be better. But he had lost his touch. Named after a great historian of Rajasthan, ‘Hotel Colonel James Tod’ never quit the drawing board.

*