32. Benjamin Jesty – The Modest Vaccinator

31. The Fate Of The Halsewell 2

November 26, 2020

33. Purbeck Stone

December 10, 2020T he current talk is of vaccines. Every time the subject of artificial immunisation is raised Benjamin Jesty of Yetminster, in Dorset, springs my mind. He was a classic example of an original inventor neither seeking, nor receiving credit. You've never heard of him? Of course not: he was gazzumped by Dr Edward Jenner, who carried out similar experiments 22 years later. Jesty was the first Englishman to discover the effectiveness of vaccination by trying it out on his own family in 1774. The only earlier record was of a German, Jobst Bose of Gottingen, who did it five years before him. Despite the awards he received, the modern fame of The Jenner Institute and everything that surrounds his name, Dr Jenner was not the pioneer: he merely exploited a business opportunity.

Farmer Jesty's attitude was clear. He knew the accepted lore that milkmaids never caught lethal smallpox and assumed that their contact with cowpox, a similar, milder disease, was responsible for their immunity. Faced with a smallpox epidemic, he decided to see if such immunity could be acquired artificially. It was known that inoculation of material from smallpox victims into healthy people, if they survived the results, prevented them catching smallpox. Often that inoculation gave patients full blown smallpox. 18th century newspapers advertised itinerant inoculators, but it was not unusual to read reports of resulting deaths after they passed.

Benjamin Jesty, the tenant of Upbury Farm, in Yetminster, who had already caught cowpox from his cattle, presumed himself safe from smallpox. The rest of the family were not. He was unwilling to risk their lives with a travelling inoculator. Why not mimick the system more mildly by treating them with less-virulent cow pox? In nearby Chetnole he heard of pox-infected cattle and, using a household needle, introduced matter from an affected cow into his wife's arm and those of his children. His wife suffered a bad fever for several days. The effect on his children was less severe. All recovered unharmed and came through the smallpox epidemic unaffected.

Benjamin Jesty became a victim of that successful experiment. The local reponse to this enormity of putting animal matter into his family's bloodstream was gross hostility. It was forgivable when the concept was so revolutionary. They thought vaccination from cattle ungodly, might result in some terrible anomaly. Would they all grow horns? Yetminster was no longer welcoming.

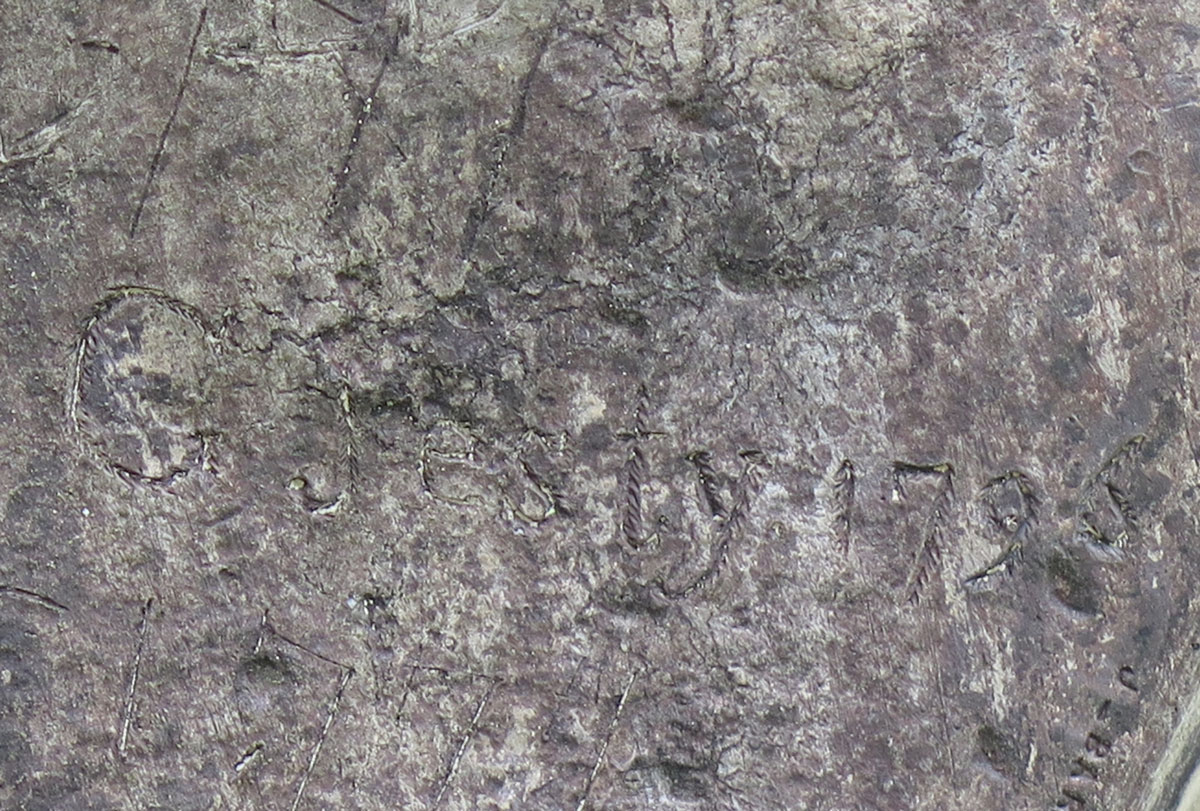

Oddly, there was a connection between The Halsewell wreck and the healer. When Jesty found the fury of anti-vaccinators too much to support he decided to move away. Morgan Jones, the Worth vicar whose florid language described The Halsewell's wreckage, had just been been appointed rector of the next village, Ryme Intrinsica (yes, there is such a place). In his Worth hat he knew that Dunshay Manor was being offered for lease and informed Jesty, who applied for it and moved. Recently, I found his youngest son's name incised into the lead hopper of Dunshay's gutter: G Jesty 1796. That must the year they settled in.

Dr Andrew Bell, appointed Rector of Swanage in 1801, had newly returned from India; there he developed the Madras System of education to counter a dearth of teachers: pupils were encouraged to teach each other. An opened-minded philanthropist already impressed by Jenner's reputation, he took up vaccinating in Purbeck and, through his role in encouraging education, persuaded local teachers to do the same. Naturally, he was interested to find an earlier vaccinator living nearby. He met Jesty, sympathising with the way he had been sidelined. While lecturing at the Jennerian Society of London, Bell mentioned the neglected pioneer.

Benjamin Jesty was duly invited to address the Society and, as the earliest inoculator for 'Cow Pock', was asked to sit for a portrait, now in Dorset County Museum. So it was Rector Bell who introduced Jesty into London, where Jenner, having been awarded the huge sum of £30,000 for his discovery, was being feted. Jesty appeared in his usual rustic clothes no doubt with a strong Dorset burr. According to another local vicar, The Society was 'much amused by his manners and appearance' his clothes being 'peculiarly old-fashioned'. That must have diminished him in their eyes while increasing him in mine. He allowed his son to be inoculated with smallpox to prove his immunity then he was presented with some memorial scalpels and sent home to Dorset obscurity. He did not object. But truth remains truth: every report crediting Jenner with Jesty's discovery is a foray into falsity – and a glance towards Jobst Bose wouldn't come amiss.

Settled in Dunshay/Downshay, Jesty didn't give up vaccination. In Worth church a plaque inscribed to Mary Brown mentions that her mother, Abigail '...was personally inoculated for cowpox by Benjamin Jesty of Downshay in this parish, the first person known to have introduced the practice.' He ended his days at Dunshay, 200 metres from my caravan, a refugee from his success, and is buried beside his wife in Worth churchyard. His prominent headstone reads: “Sacred to the Memory of Benjamin Jesty of Downshay, who departed this Life April 16th 1816 aged 79 years. He was born at Yetminster in this County and was an upright honest Man particularly noted for having been the first Person (known) that introduced the Cow Pox by Inoculation and who from his great strength of mind made the Experiment from the Cow on his Wife and two Sons in the Year 1774.”

There's good reason to celebrate Benjamin Jesty! Modern anti-vaccinationers, unprotected by the ignorance of those Yetminster folk, probably bear the mark of childhood vaccination against smallpox, a horror none of them ever witnessed. Vaccination obliterated it, but not until I had seen its results. You couldn't cross Asia in the 1960s without meeting survivors with terribly ravaged faces, those white-blind eyes. Smallpox-disfigured children and adults were common among the ranks of beggars. And in England the polio-lame kids of my generation; where did they go? In Asia each polio kid, paralysed match-stick legs crossed, went around the streets on a wooden platform set on castors. You don't see them now. Immunisation saved the next cohort. Trendy anti-vaccinators and pious obscurantists can enjoy their own white-eyed blindness: sad about their kids.