33. Purbeck Stone

32. Benjamin Jesty – The Modest Vaccinator

December 3, 202034. A Pierless Bottom

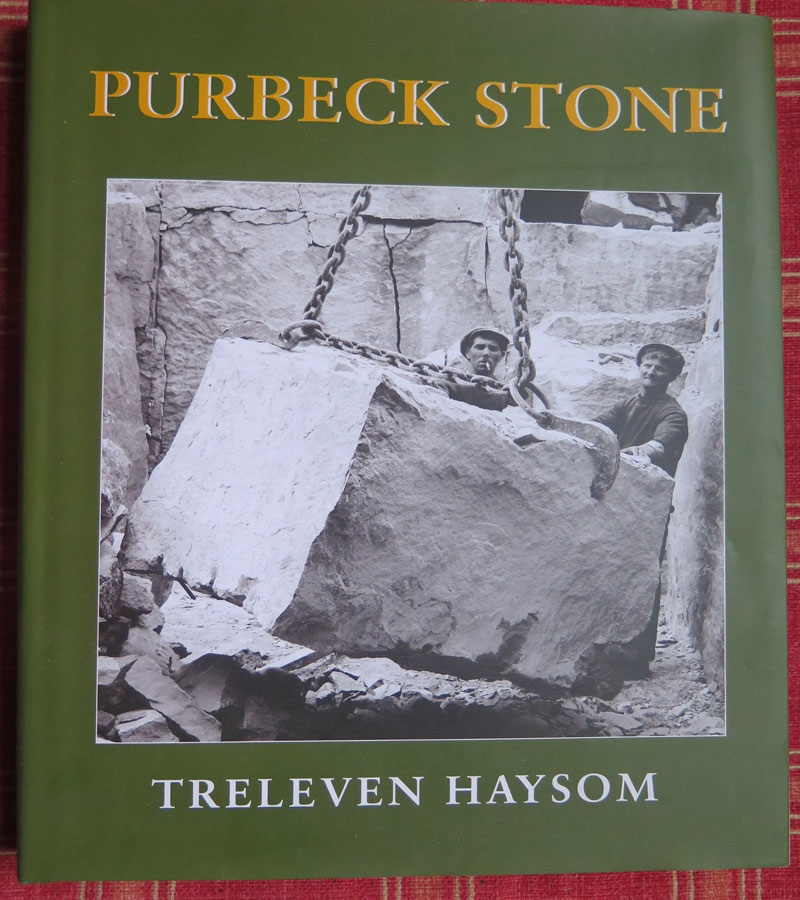

December 17, 2020D ovecote Press (www.dovecotepress.com) has just published Treleven Haysom's 'Purbeck Stone'. Reading through, I was impressed, but not surprised, by the enormous amount of information it offers on Purbeck's most important industry. It is the result of a life-time 'hands-on' channelled into deeper research. But then, friends since boyhood, my neutrality could be suspect.

Trev introduced me to Purbeck stone; most I know on the subject came from him. As boys in the late fifties, we'd often meet at his father's quarry on St Aldhelm's Head, then lightly-mechanised, tinking to the sound of metal on stone. From there, drawn by a mutual interest in birds, we'd explore the coast. But his eyes were also open to anything concerning stone and its exploitation. He would point out the different beds, sketches of sailing vessels incised into the face of cliff quarries, accompanying dates and calculations, initials and the names they might represent. He showed me the wreckage of a considerable pier, constructed to handle stone, which fell victim, perhaps, to the Great Storm of 1824. On the cliff-edge the 19th century timber upright of a crane still stood and, at Winspit, the last cliff quarry had just ceased operation. There was a cannon, perhaps raised from The Halsewell, upended at the mouth Pier Bottom. Inland, we explored the precarious lanes of underground quarries.

He went on to study masonry and work on Chichester cathedral before taking over the quarry. The business yielded domestic stonework – paving, wall stones, polished fireplace, shelves and inevitable headstones. There was a contrasting line in fine masonry ranging from the fabric of modern secular and religious buildings to mnediaeval church restoration. That was the most demanding work. After the war, Trev's father set about restoring London's Temple Church, severely damaged by incendiary bombs. It had been rich in carved and polished Purbeck Marble, a bed no longer in much demand.They opened a quarry specifically to supply the stone.

The success of that contract must have attracted much of the restoration work which followed. The iron-rich 'marble' – no true metamorphosed marble but a dark, shelly limestone - was vulnerable to oxidation, decay. Ornate carved capitals had to be carefully copied and polished. There were narrow, lathe-turned marble shafts to replace, the segments of moulded pillars to be worked by hand. Most of that exacting work fell to Trev.

In the book, he disseminates the knowledge gathered from a lifetime of research, from his father's experience in the industry and that of older hands, each an expert telling what he knows. Trev listened, read, remembered, sought evidence to fill in forgotten details. The book is born of careful looking, reading and listening. On the way he picked up an honorary doctorate from Bournemouth University.

The text is dense, diverting, rich in all manner of details. He covers the Purbeck beds laid down in water of low salinity ranging from brackish lagoons to fresh water. As conditions changed so did the nature of the layers, a bed of limestone giving way to one of soft clay. The stones varied in hardness, colour and fossil content. Purbeck Marble, uppermost in the Purbeck series, earns its own chapter. Blue, green or grey, dappled with watersnail fossils, it was England's most important mediaeval decorative stone, peaking in the 13th century. Burr, close beneath it, was the most popular local building stone of that period, with a brief 19th century revival.

Cleaving beds fed a late 17th and 18th century need to pave sidewalks, floors, tiled roofs for expanding London. After the surface exposures were dug out, quarrymen followed the sloping beds underground. Other outcrops of Purbeck stone at Peveril Point and Durlston Bay provided exposed stone easily loaded into boats.

Cliff Stone, the more-massive marine limestone forming cliffs along the south coast of Purbeck, was heavily quarried in the 18th and early 19th centuries, creating cherished features such as Winspit and Dancing Ledge. Much of it was carried by sea eastwards for Ramsgate's massive 18th century harbour project. Cliff stone was also a valuable source for sinks, kerb and staddlestones and remains favoured for building.

The Bankers beside Swanage's shore became the merchants' exit point for stone. Here it was stacked before it left first from the beach, then loaded from a new, now 'Old', pier before, with the coming of trains in 1885, focus shifted to the railway yard. Finally came lorries. Modern machinery tore the land apart for stone.

The book is richly illustrated by buildings and their furnishings of fonts, royal tombs and effigies. There are Newfoundland headstones, London paving, tiled roofs and more kerb. Early transport and mining techniques are depicted, but the illustrations shouldn't distract from an excellent text. 'Purbeck Stone' may be built on, altered but not surpassed.

And my connection with all this stone? Having studied Geology and Zoology in London, both relating to stone and fossils, I was never tempted to follow a career in either but set off to travel. That led to my own niche. Working at Trev's quarry helped fund those regular overland journeys between Purbeck and India. Later, it supported research into Rajasthani murals. Never a craftsman, most of my quarry tasks were mechanical, using a circular saw to cut paving, fire surrounds, mantlepieces, windowsills, hearth stones, headstones; polishing them all with a rotating wheel on a jointed arm known as a 'Jenny Lind', oddly named after a Swedish opera singer! I grew familiar with the popular varieties of Purbeck stone and cliffstone. When no work was available at the quarry, there was always hotel waitering.

From 1975 onwards I always carried a camera and, having already started to write occasional articles, branched out into photojournalism, then books. It was not until 1984 that the mural research attracted funding. Afterwards, there were scholarships for work in India and Pakistan.

Meanwhile, the subcontinent was rich in stone; white marble mined at Makrana (the Taj Mahal came from there), red and yellow sandstone shaped into finely carved palaces, grey Kota stone cleaved for paving, granites turned to headstones. They travel, also, the last two well-established in the British market.

<>*V*<>