82. A Last Glimpse Of Labels And More Birds

81. A Trade War In Pictures 2

January 4, 2024

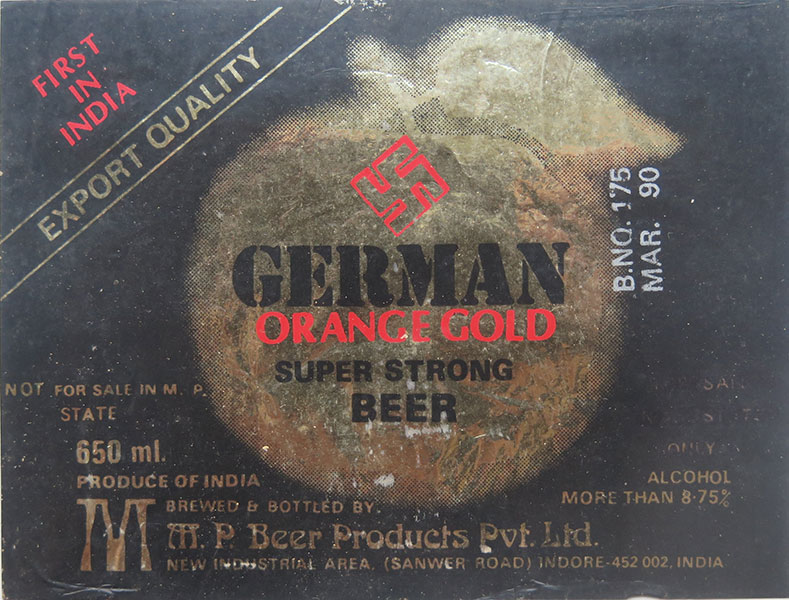

83. Animal Life Usually Starts With Eggs

March 7, 2024L ooking through a folder of ticket images, I found a more recent example of Indian labelling with which to open this blog. In the 1980s, when beer became increasingly popular in India, several companies launched new brands, some signing deals with foreign manufacturers famed for their beers. That was a time when everything ‘foreign’ seemed superior, so it was good marketing for one company to draw attention to its German cooperation. Calling it ‘German Beer’, they looked for a catchy logo and arrived at one with strong Indian and German associations. The German partners were unimpressed and the crooked cross was rapidly replaced by a lotus flower and ‘German Beer’, briefly so popular with foreign tourists, lost its appeal.

My year moves to a pattern. As January breaks, it is time to start thinking of summer crops. I planned to push some of the vegetables forward this year so that the garden would soon be yielding, but a sharp frost turned the earth concrete. That broke to milder, wetter weather so I dug a bed and planted three rows of broad beans. With luck, they should be ready by late June. Then there are other seeds. Most need encouragement indoors – tomatoes, other beans, aubergines starting their lives on the windowsill next to several pots of chillies. But it is only natural to be lazy about garden work until there is enough sun in the sky to make the task pleasant. At present, after a wet winter, an hour in the garden weighs my boots down with clinging mud.

There is the wild Spring to think about, too. I have already visited sites along the Purbeck cliffs to check on the first guillemots, most of them already in breeding plumage, having given up their sterile white cheeks in favour of the chocolate décor. It is hardly appropriate to refer to ‘summer’ as opposed to ‘winter’ plumage. The birds visiting the breeding ledges in autumn in preparation for next spring are already chocolate-faced and will remain so until August, after their young have left. Then they rapidly moult to become briefly flightless, revealing efficient little flippers in place of the usual still-small, but functional, whirring wings that are needed to lift them off from the water. One auk, the razorbill, is claimed to have the smallest wing area in relation to body weight of any flying bird. Flight is only necessary for these birds to reach high and dry ledges on which to lay eggs and raise their young. The rest of an auk’s life is in the sea.

Like the penguins, the largest auk, the Great Auk, a giant razorbill, evolved to flightlessness and prospered. It bred on rocky islands in the North Atlantic where it was safe from predators. But it was all a mistake: it failed to anticipate boatmen, who became such a presence on the busy seas between Europe and America. By the mid 19th century, the Great Auk was as dead as the Dodo, that large, flightless Mauritian pigeon. Both had succumbed to hungry sailors. What better source of meat than fat, flightless birds? As a boy, I collected old books on wildlife. The engraving in this blog came from one of these, which was published in 1840 – four years before the Greak Auk became extinct. The early paddle steamer shown on the left is a nice touch. Here, the author describes the fate of one of the last Great Auks: ‘Mr Bullock…when making a tour of the Orkney Islands, was informed by the natives that only one male had appeared for a long time, and…regularly visited Papa Westra. The female, called by the people the Queen of the Auks, was killed just before his arrival. Mr Bullock chased the king, or male, for several hours, in a six-oared boat, but without being able to kill him. Though he frequently got near the bird…it appeared impossible to shoot him. The smallness of the wings render them useless in flight…’ but ‘admirably adapted to its mode of life, acting as fins when the bird dives under water, and enabling it to pursue its prey with astonishing velocity.’

In short, in Arctic seas, the Great Auk was well advanced along the same evolutionary track that had led, in Antarctic seas, to the King and Emperor penguins, but it arrived too late! The last Great Auk was killed in 1844. As for eggs, a recent writer claimed that global warming has resulted in some British auks laying two weeks earlier. That immediately jarred with me. As Purbeck boys, we would sit on a promontory we called The Point, at a place in Purbeck called Durlston. This overlooked a large, open guillemot breeding ledge. In Spring, cycling there after school, we’d look out for the first egg or incubating bird. It became apparent that they started laying around St George’s Day, 23rd April. Nothing in the decades that followed has persuaded me that this laying date has changed. In 1971 our viewpoint fell. We could no longer look down on that big, busy ledge. By then, kids had lost the freedom we had to climb all over those cliffs or descend to Tilly Whim Caves and swim along beneath them.

Durlston became a country park for nearby Swanage. One of the features of this new regime was a video scanner focused on that same guillemot ledge. Recently, I walked there to ask about more modern records of laying dates. But that is not how things work nowadays. No one was available to supply the information: but it is all easily available online! My schoolboy diaries give the first eggs as: 1957: 28th April, guillemots incubating on ‘A’ Ledge (my term for that big Durlston ledge);1958: 30th April - No guillemots on ‘A’ ledge. 1959: 23rd April - One guillemot with an egg on ‘A’ ledge. The others flew out. 1960: 29th April - 2 guillemots incubating on ‘A’ Ledge.1961: 27th April – a Guillemot incubating on ‘A’ ledge – also a broken egg. 1962: 23rd April some incubating. Over the decades that followed when I looked towards guillemots in Spring I never had reason to question St George’s Day as a guide. The online Durlston records were reassuring: 2005: First egg seen 2nd May; 2006: First egg 24th April; 2007: 24th April; 2009: 18th April; 2010: 22nd April. 2011: 24th April. 2012: there is a delinquent 15th April, but that egg disappeared. Then came Ravens, which ate the eggs as fast as they came, and the on-line records appear to have gone the way of the eggs.

All those Purbeck guillemot ledges are deserted by late July. All but one unique record. In 2013 a colony I visit was deserted in late July, as usual - but for a single couple with their chick. What was the story there? Why did that pair lay so late? They left around 7th August, the latest Purbeck Guillemots I have seen.