81. A Trade War In Pictures 2

80. A Trade War in Pictures 1

December 8, 2023

82. A Last Glimpse Of Labels And More Birds

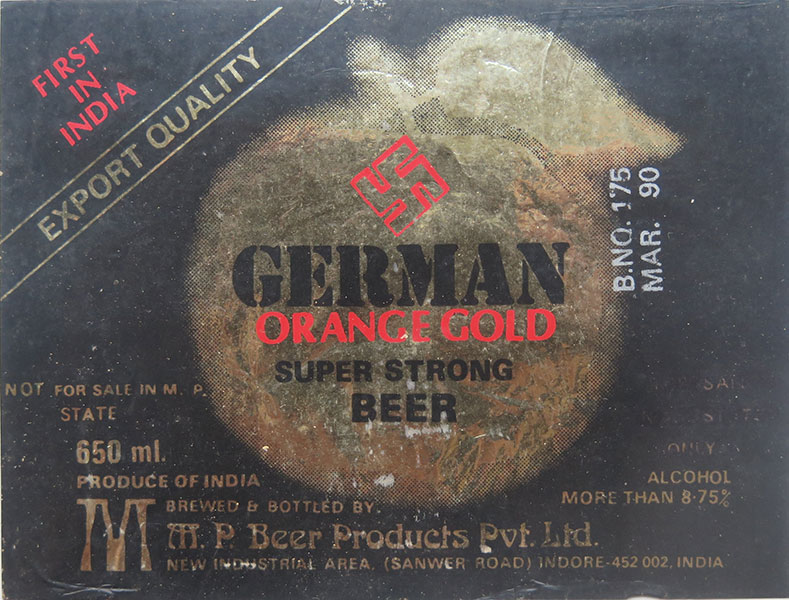

February 2, 2024L abels were not new to the 19th century British textile trade. The revolution was that picture! Developments in ephemera are hard to trace. Few folk cherish the bright packaging of today against the interest of tomorrow. Today, far more British picture tickets survive in India than in their land of origin, reflecting the success of their appeal to local taste.

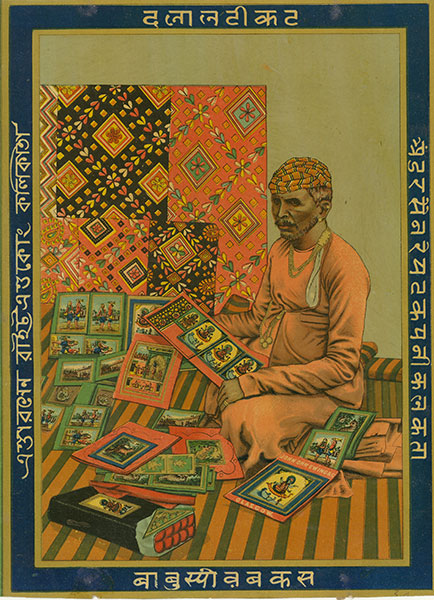

Something of the story of Indian shippers’ tickets is illustrated by a fine early 20th century label entitled, in Hindi, ‘Dalal Ticket’, a dalal being a broker. It shows a merchant named as ‘Babu Sheo Bakas’ seated on a floor covered with a striped cotton dhurry (rug). Both his name and his tight little turban identify him as a Marwari merchant, probably from one of the many Shekhawati Bania families who had risen to control the textile trade through Calcutta. The accuracy of his face indicates that it was copied from a photograph. Behind him are some samples of British machine-printed fabric rich in Turkey Red dye (by then synthetically mass-produced). Carefully researching their market, the manufacturers used a preferred Indian palette and, mimicking traditional methods of textile decoration, they produced imitation block-print, applique and tie-dye motifs. Spotted ‘bandana’, so popular in 19th century America and Africa, was merely a machine-printed version of Indian tie-dye, ‘bandhani’.

Sheo Bakas holds a sheet of identical tickets; others lie on the floor or are leaned up against the cloth samples. On the floor is another print of the label he is holding and it is possible to read the name of ‘John Orr Ewing & Co of Glasgow’ along its border. An identical label is attached to the parcel in the foreground, which has been opened to reveal small rolls of scarlet cloth, perhaps lunghi (sarong) or turban lengths. The captions in the side borders of this ‘Dalal Ticket’ name, in Devnagari script (right) and Bengali script (left), another company, ‘Anderson Wright of Calcutta’, presumably the importer for whom Sheo Bakas was the broker.

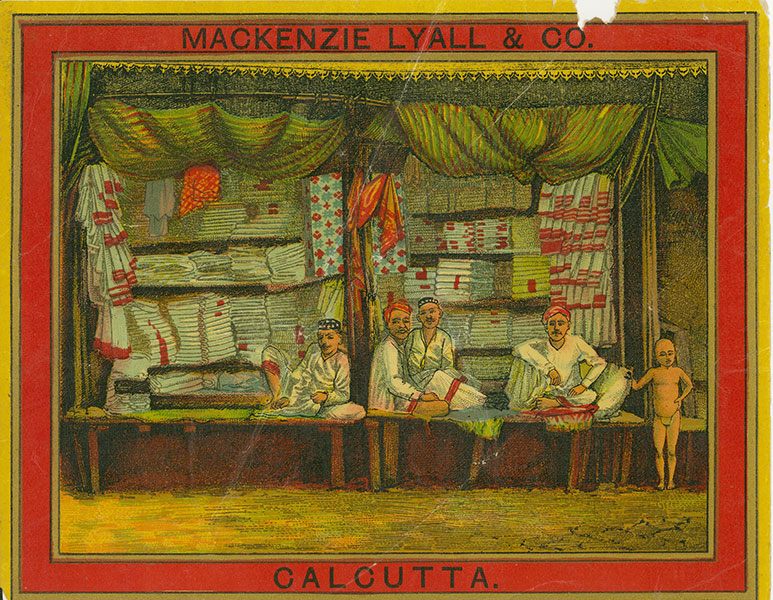

Another ticket illustrates the next stage in marketing; the bazaar shopkeepers. Again, they are wearing those tight little Bania turbans. The cloth they sell is mostly white, bleached save for a border or a stripe of that wonderful, fast Turkey red. This dye, derived by a complex process from the root of the plant madder, had been synthesized as alizarin by German chemists around 1870. This made it cheaper and readily available, revolutionizing the dyeing and printing of cloth on an industrial scale. Many tickets specifically mention ‘Turkey Red’ in their captions.

The advances of western technology were frequently recorded in the subjects chosen for tickets and, along with the fashions worn by any Europeans depicted, help to date them. Iron steam-ships feature, railway locomotives develop in form and bicycles and cars make their appearance. Often events or the people themselves indicate the period. Edward VII was shown in his coronation garb in 1902, his accession being a major event after Victoria’s long reign. George V’s coronation, featured ten years later, to be followed by illustrations of the royal couple making a state visit to Indian. But there were good reasons not to choose many subjects too tied to an era: fashionable images soon became redundant. Sometimes the demise of a company help to date a ticket: presumably the popular label showing an Indian ruler and publicizing Hugh Balfour & Co disappeared when that company went bankrupt in 1878. That one was among those I collected in Shekhawati, its matt finish also indicating an early date. Another early matt ticket showing Shiva and his family, produced by Anderson Wright, was set under glass on a Shekhawati haveli wall and used as the focus of a mural dateable to around 1870.

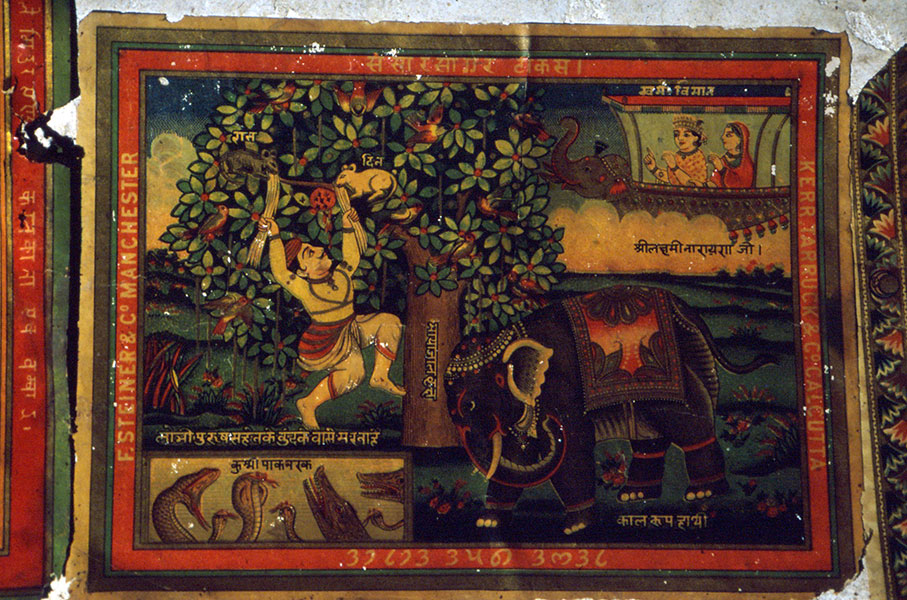

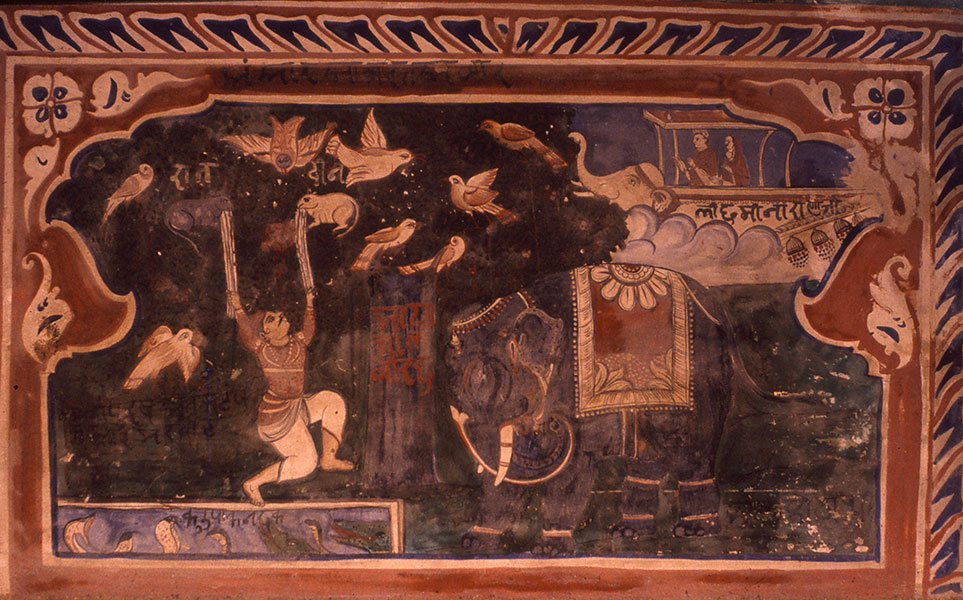

Occasionally, a label’s image revealed a stylistic background. After showing Richard Blurton of the British Museum an odd boating ticket in an unmistakably Bengali style, he sent me a card with a very similar image, labelled as Kamile-Kamini, displayed in a Calcutta museum (see pictures). In Jaipur Museum I discovered a 19th century box bearing a painting closely resembling a familiar ticket produced by F Steiner of Manchester. Labelled ‘Sansaar Saagar’ (‘The World is an Ocean’ which, Ravindra Sharma tells me, is a common metaphor), it shows a man struggling to escape a serpent-filled hell to reach his saviour, Lord Vishnu, in his mythical airship. Clearly someone cruised local museums in search of inspiration for such tickets. But this Sansaar Saagar image, having escape the museum, then took a further leap: it was copied by muralists on at least three separate haveli walls in Shekhawati!

The transition from ticket to wall didn’t stop there. Arvind Sharma gave me a label on which was drawn a pencil grid, clearly with the intention of enlarging it and copying it onto a wall. Painted ticket images are identifiable in murals on many Shekhawati buildings. Sometimes I became familiar with an image in a mural before discovering that it was taken from a ticket: in one haveli room was a picture of a crowned queen. In its top border was carefully copied the word ‘GRAHAM’, a major Manchester company and in its bottom border the ‘Yds’ and ‘No,’, each followed by the space, which was printed on most tickets. There could be no doubt of the origin of that image. Years later, looking through Adrian Wilson’s great collection of tickets, I found the one from which the painter had copied! At the same time, I recognized another print of Wilson’s as the source of a mural in Mandawa. The original print, supporting swadeshi (Indian-made) textiles, shows a British woman factory-worker in dungarees leaving India with a bale of cloth under her arm. The message was clear: no one wanted to buy her foreign cloth. The mural image is almost identical except that the figure has become a man in a trilby with a rucksack on his back, again leaving the outline of India. That must date from 1942, the ‘Quit India’ movement, and he is a Briton dutifully quitting.

The turn of the 19th century saw the zenith of the British Indian Empire. From there it was all downhill. Other countries were industrializing and some were undercutting. After the First World War the Japanese began to dominate the Indian textile market and India’s own industrial production was steadily expanding. Picture labels were among the expenses these rivals put aside. They had passed their prime. But pretty, folksy labels survived Independence to compete within India. I remember carrying home a bag of cheap little packets of Indian bidis, each with a colourful picture label, remember, too, being stopped at Greek customs. Sure those cheroots must contain drugs, they were quite rude when, disappointed, they had to return them.