80. A Trade War in Pictures 1

79. Back To India Via Sylhet

November 2, 2023

81. A Trade War In Pictures 2

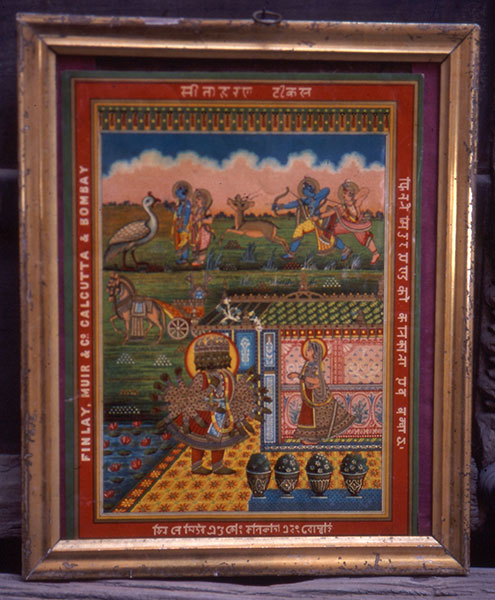

January 4, 2024I n July, an American researcher, Sue Meller, wrote to me announcing her new book, ‘Labels of Empire’, since I was among the first to recognize their importance and write about them. She has created a magnificent, richly-illustrated tome full of information. Arriving in Calcutta, then India’s great port and capital, at the turn of the 19th century, along with the millions of miles of Manchester-made cotton cloth they were intended to promote, the labels I found were designed specifically for an Indian market. From 1972 onwards I would come across them decorating ornate Rajasthani buildings, often depicting themes drawn from the Hinduism embraced by most of the merchants and brokers handling the cloth. These men came from Shekhawati, a thousand miles away in desert Rajasthan, attracted to Calcutta by that vast trade. Back in the homeland, their families set to commissioning a wonderful array of buildings. These would include a haveli (mansion), a temple to the family’s preferred deity, a memorial chhatri (pillared dome) usually raised to the merchant’s father, a well, marked by two or four tall pillars, and a caravansarai to accommodate passing merchant caravans. As a final touch, the local masons covered the walls with painted pictures and decorative designs.

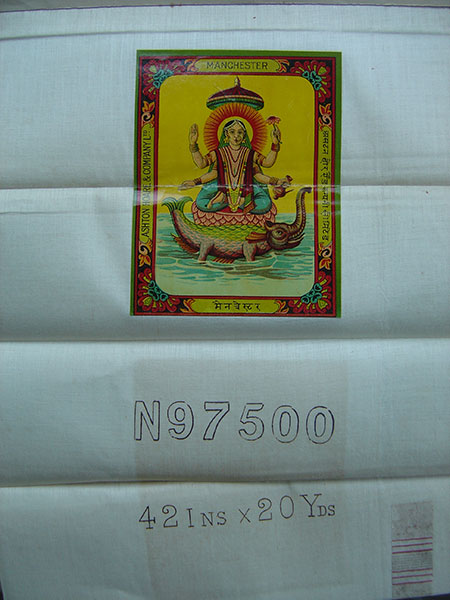

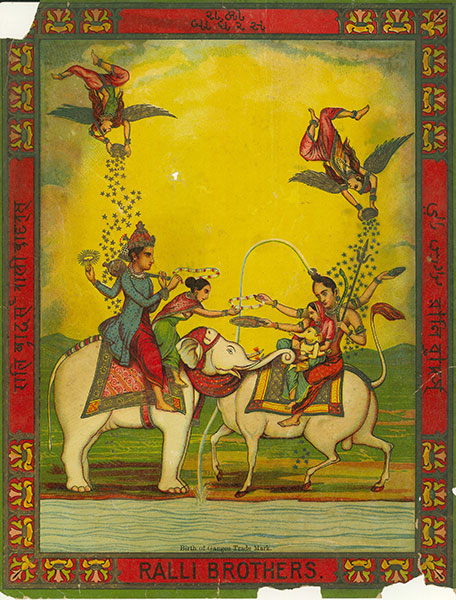

I passed many years researching those buildings and their murals then was commissioned by the Indian National Trust to document them. With a local teacher, Ravindra Sharma, we examined, described and photographed 2260 buildings, most of them painted havelis. The labels were incidental, glued to the walls of rooms. From them I learned the names of many long-defunct companies based in Manchester or Glasgow and became familiar with the variable images they purveyed. Most labels were quite large, 10 x 15cm or 15 x 22.5cm, with a glossy finish, combining a rich palette of ten or more shades and often crowded with figures. Advertising many different manufacturing or importing companies, they depicted a large variety of subjects. In some havelis they named a single company for which the merchant, that householder, was broker. Some labels, printed with deities, became gilt-framed holy pictures in shrines and temples. Decades of candle smoke or oil lamps had discoloured them. When travelling more widely in the subcontinent, I found them more sparsely everywhere, even in derelict Hindu and Sikh buildings in Pakistan. Clearly, the output had been enormous; that they far outlived the companies they named illustrates the success of their campaign.

Later, many merchants moved away to settle in the city where their business was situated, leaving neglected havelis to collapse or be demolished, often revealing displays of labels. Occasionally, it was possible to ease one off with a knife. When people learned of my interest, some would bring examples to sell, sometimes under the impression that they were of great value. Unfortunately, my INTACH funding was spectacularly low - ten percent of what was originally agreed - so there was little to spend on pretty things, nevertheless, I gathered a small collection and photographed many more. Each label had a layer of gum applied to its back and often this contained red fibres from the length of Turkey Red dyed cloth to which it had been applied.

The labels became a side-kick to wall-painting research and my knowledge was limited to what I gather in desert Shekhawati. It was soon clear that the technology for printing such images was not available in India at the time they were being produced so, like the cloth, they were probably printed in Britain. Always short of funds, I wrote articles on them for ‘Country Life’ (London 1991) and ‘The India Magazine’ (New Delhi 1995). In the latter, the editor introduced a major error, misunderstanding some abbreviations. On each label there are two abbreviations, each followed by a space. One is ‘No.’ (indicating the cloth’s batch ‘number’) and the other ‘Yds.’ (indicating the number of ‘yards’ of cut cloth). The seller would fill in the spaces by hand. The editor had replaced these with ‘No’ and ‘Yes’!

My ‘Country Life’ article resulted in a letter from Adrian Wilson from Manchester. He had also been inspired by the labels, which, he told me, were correctly known as Shippers’ Tickets. His research in Manchester had yielded most of the story of their production. He had traced the companies and their tickets, which, although India was by far the largest market, were aimed throughout the world, each culture having its own preferred subjects, demands and taboos. Large printing companies thrived on the demand, having separate offices employing qualified staff to check each image, its colouring and language to satisfy the population it served.

Wilson & I have remained in contact ever since and he has gathered a large collection of worldwide shippers’ tickets along with a great deal of information. He discovered that printing of pretty labels started in Germany in the mid 19th century. British textile companies began to buy them in bulk to attach to cloth, then began to order their own designs. Soon, the firms turned to Manchester printers for such ephemera as shippers’ tickets. Amongst these printers was B Taylor. According to Wilson, he employed twenty artists and each design had to be sufficiently individual to be registered for copyright. He mentions that some ticket artists achieved fame in other fields: Adolph Vallette, from France, working in Manchester for Norbury Nazio, also painted impressionist urban scenes there and was teacher to the artist, L. S. Lowry.

There must also have been designers in the headquarters of each country gathering images and checking through each proposed picture and its colour scheme. Most Indian tickets depicted scenes from the Hindu pantheon. The iconography is strict, each deity being associated with set attributes and arranged in a recognized relationship to others. Major gods such as Krishna or Ramchandra were fine if painted blue, but never green. The only way to keep clear of such minefields was to put the pictures and their colouring past local folk. Sometimes the style of portrayal is that of one particular part of India such as Bengal or Madras. Surely, some of the initial sketching must have taken place in Calcutta, for example, before the design was sent back to Britain for printing?