79. Back To India Via Sylhet

78. The Loss Of A Friend

October 5, 202380. A Trade War in Pictures 1

December 8, 2023I spent the next morning writing to Horace to tell him what I had gleaned of Bangladesh. Afterwards, walking through the city, I came to a stylish Chinese restaurant and, given the very favourable black rate of exchange, treated myself to fried prawns, which must have been almost lobster size. Having passed the beggars and hungry folk in the streets, that meal preyed on my conscience. Back in the streets, I wandered through the dripping humidity and retreated into the main post office, a public cool place and sat there to read Mozart’s letters: he would never have expected them to arrive there. Moving on, I passed shops selling lengths of printed cloth and lunghis, which are likely to be expensive in Bangladesh. I didn’t even ask the prices.

Back at the house, the family served supper, then Sujit took me in a rickshaw to the station, where I took a second class seat to Sylhet. where I found a seat 2nd class to Sylhet and got into conversation with my neighbour, who proved to be a communist teacher. He was very careful about what he said but was openly critical of India and strongly in favour of the re-uniting of both parts of Bengal. He said that before Independence the Bengali leaders always got a raw deal and accused the Indian Central Government of exploiting West Bengal. But our talk was interrupted. Just outside Dacca the train stopped. As it restarted, slowly pulling away, a figure in white pyjamas ran up out of the darkness and it a white flash man snatched the bracelet watch of the man opposite me, who had his arm resting on the window ledge. A neat move, then he disappeared back into the darkness. Shocked, the man simply looked at his wrist, moving it around as though the watch might reappear.

Just after midnight the train pulled up facing the wide Kalni River and we were ordered out. The large railway bridge had been blown up at each end by the retreating Pakistani troops and the passengers were shown onto a fleet of country boats. At least the boatmen made a killing out of it, charging us a taka each. It was a pleasant diversion, a cool breeze on a moonlit night. The train waiting for us on the other side was crowded and I barely slept until I managed to get onto a vacated luggage rack. Below, a group of soldiers were playing cards. At dawn, the train pulled up and the passengers got down to wash then pray. It was after six when the sun rose on an attractive landscape. Now the train was climbing between hills where the jungle had been cleared in places to make way for tea gardens. I dozed off and only woke when a man told me that we had reached Sylhet.

Quitting the train, I crossed the river and, sweating profusely and bursting for a shit, took a room in the Gulshan Hotel. It must have been about eleven o’clock and the dysentery had returned so I spent most of that day resting, reading and shitting water. I managed to escape to the market and pick up some biscuits and a couple of tins of condensed milk. One was skimmed, the other full-cream milk but, oddly, they were the same price despite the contents of the condensed milk tin was actually more. Finding a chemist’s shop, I asked for pills to stop the flow. I didn’t stay out long, returning to my castle and its relieving lavatory. Like elsewhere in Bangladesh, beggars were everywhere.

The bedroom was provided with a mosquito net, the first I have ever slept under. In the morning I had the pleasure in killing a mosquitoes that had got into the net and were unable to get out. Each was filled with my blood. Feeling rather better, I had a shower then a breakfast of two ducks’ eggs, toast and tea before exploring the town. The tourist office offered very little apart from giving the rather uncertain site of the bus stand, the rather uncertain site of the frontier and announcing that the frontier village, Tamabili, was 15 miles from the frontier. That I refused to believe. The tourist officer displayed an inability to relate to a map which is true of almost every one in the subcontinent – a racial generalization that actually works! Bought some bananas and just wandered around eating them while ignoring the stares of the populace.

Back in the room, I read through the newspaper, Bangladesh Observer which, today anyhow, had quite good overseas coverage. And pondered whether to leave tomorrow or the next day. There seems little point in hanging around here. I’ll visit other parts of the country - the Hill Tracts and Cox’s Bazaar - another time. I never did. I was getting enthusiastic over the concept of a united Bengal and thought of returning as a fluent Bengali speaker. But after this sentence there is a note in my diary: ‘Now, Ilay, you’re a big boy: you are going to settle down.’ Not yet, I wasn’t! Along by the river people were selling what appeared to be some sort of live flatfish. Getting closer I realized they were terrapins lain on their backs, white undersides up, slowly dying in the sun. They were astonishingly dorso-ventrally flattened. The boats here are built to a different form, too. The small ones are even longer and more slender than those elsewhere, but there are also much longer ‘sampans’ with the roofing stretching much of the length of the boat. I walked over the bridge, which rises well in on the bank so that the road runs beneath you. A group of people had collected around two youths who were, I presume, trying to sell copies of a new poem. They stood some way apart and the elder of the two would start chanting the words, immediately taken up in unison by the younger. Occasionally they would walk across and change places without interruption. The effect was impressive. The sun was low as I started back over the river, leaning on the railing to watch the boats paddling to and fro on the smooth water, the reddening sun behind them.

Britain is full of Sylhetis. Somehow they long ago cornered the ‘Indian’ restaurant market there. Sylhet is full of travel agencies offering flights to London. A handsome boy, one of those Bengalis with refined Mongolian features, overtook me then came back to talk. As soon as he opened his mouth, I knew he was British. From Sheffield, he had been at the Bangladesh rally I had attended in London. He mentioned the instability he felt as a fairly recent immigrant to Britain. I realized that he felt worried about his return to England and felt ashamed. Amongst the many beggars were charlatans. Some had stacks of some vaccine with which they were ‘treating’ the gullible with. They would withdraw the liquid with the syringe and rub it on the affected part. God knows what it was; the label was in Bengali. I prefer the doctors that sit surrounded by snakes, skeletons, skins, live and dead lizards, skulls fitted with bright eyes and all the weird roots. At least they offer drama.

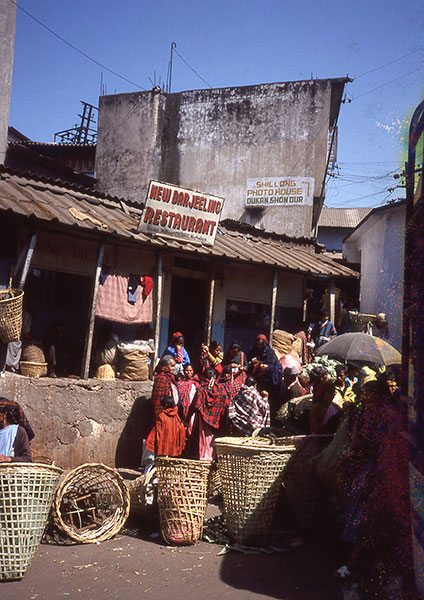

Next day I boarded a little wooden bus with very hard seats arranged longitudinally (there are many such buses in Bangladesh). It soon filled up and moved very slowly towards Tamabil – the 25 miles took some 3 ½ hours. There were diversions where culverts and bridges had been blown up by retreating Pakistanis. A large group of fishermen walked by with nets and ‘live baskets’ and many were fishing in each river in the rivers there were many men fishing clad in the absolute minimum. Dust devils crossed the dry paddy waiting for the rains. A solid wall of scarp lay ahead: India. I left the bus and walked to the frontier. I was hassled because I had declared 50 Indian rupees on entry and now had 55. I was only the 13th foreigner to leave by Sylhet this year and the police took ages filling out the form. The Indian check-post was no better: among my physical details they wrote that my colour was blue. Meanwhile, I missed the bus to Cherrapunji and Shillong.