28. Labels And Prints

27. Fatehpur – An Old Capital

October 29, 2020

29. Mandawa

November 12, 2020A mongst the murals we came upon many copies of Western prints, alien themes and subjects. Mass produced and easily accessible, these were treasured everywhere across the subcontinent. Later, looking at murals in Lahore Fort, Pakistan, there were such copies dating from 1620. The city had been the Mughal capital and the emperor Jahangir (1605-1627) was a free thinker with an interest in art and wildlife. He encouraged all religions in his court and amongst them came Jesuits from Portuguese-ruled Goa, their prayer books stuffed with monochrome prints of the holy family and a cascade of saints, many of them produced in Antwerp. Thinking he was interested in conversion, they gave them to him freely, also an illustrated bible. Alas, his enthusiasm was for the medium, not the message. He passed the pictures to his painters to copy. Examining a pavilion decorated with Christian saints thought to be British work, I realised they had been stencilled onto the wall by Jahangir's artists. Some, including a pope, even retained the telltale dotted outline. Anathema to the grim orthodox, such pictures were obliterated by Jahangir's puritanical grandson, Aurangzeb. But god works in wondrous ways: in the 1970s they re-appeared brightly from the layers of whitewash which had protected their colours: the destroyer proved conserver. Similarly, a nearby dome became alive with realistic birds and Baroque winged-head putti whilst, darkly outlined beneath lime, Persian-style angels began to emerge.

In high Mughal times foreign pictures were luxury items and only royalty could risk copying such alien figurative images. Faith is fickle and a change of regime might condemn them as blasphemous. As time advanced mass-produced images became ever easier to come, ever more acceptable. In Europe colour printing advanced to a fine art.

Looking at murals in Shekhawati's towns it is obvious that some detailed panels were copied from foreign prints, their subjects relating to the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Both style and subjects were alien. The previous blog mentions a print of The Delhi Durbar copied onto a Fatehpur wall. A common image on Nawalgarh buildings is a British railway station peopled by heavily dressed passengers from a colder climate. Other copies depicted those same folk out in early models of car. Another stolen image there shows boatmen, even more heavily clad, on an icy sea fending off polar bears. Only the bears appear improbable.

Years later I identified the print from which it had been copied; the poses are identical but the attackers had been walruses, creatures too improbable for the painter to launch into Nawalgarh. He had replaced them with something more familiar - white bears. A favourite copy on the south wall of Churu's Surajmal Banthia Haveli (Churu 4 in The Painted Towns of Shekhawati) is taken from a print of Jesus exposing his Sacred Heart. Again the artist, unfamiliar with either the pose or the fellow, has wandered. The heart is unexposed and the two fingers pointing heavenwards are given a cigar! On a neighbouring wall are illustrations of named royalty: 'Prince Louis at Saafeld', 'Jerome Bonaparte, King of Westphalia', 'Emperor George V, King of England' and, more locally, 'Haldighat – Akbar and Maharana Pratap'. A Mandawa painter, Balu Ram, clearly had a book on Venice from which, in the 1930s and '40s, he copied gondolas, sighing bridges and Venetian scenes onto patrons' walls.

One important source of inspiration directly involved the merchants financing most of Shekhawati's buildings. Glued to walls inside old havelis are picture labels, often on Hindu religious themes, captioned in English, Hindi, Bengali or Urdu and bearing the names of English, Scottish or, occasionally, French textile manufacturers. Known in the trade as tickets, these must have been designed in Calcutta, where the themes were familiar, then printed in Britain, where the technology was advanced. Some bore the words 'Turkey Red', a synthetic dye imitating madder for which, prior to synthesising, Turkey had been famous.

Manufacturers supplied such advertising tickets to Indian importers, who applied them to the cloth they distributed. One early 20th century example, 'Dalal Ticket' (a dalal is a broker) shows a merchant, named as Babu Shiv Bux, the face taken from photograph, in his shop seated in front of printed samples and about to apply tickets. A contemporary miniature of a Calcutta-based Fatehpur merchant following the ticket format and style must derive from the same designers. Again, his face is drawn from a photograph. Such Hindu images would appeal both to the merchants, mostly Hindus, and the majority of their customers. Treasured in gilded frames and advertising long-dead British companies, some are still the focus of worship. Other subjects included Muslim monuments such as the Taj Mahal, popular folk tales, portraits of British monarchs and military pictures. One Manchester ticket, entitled 'Indian Sharpshooter', shows a smartly-uniformed, turbanned soldier, precariously perched in a tree, aiming his musket.

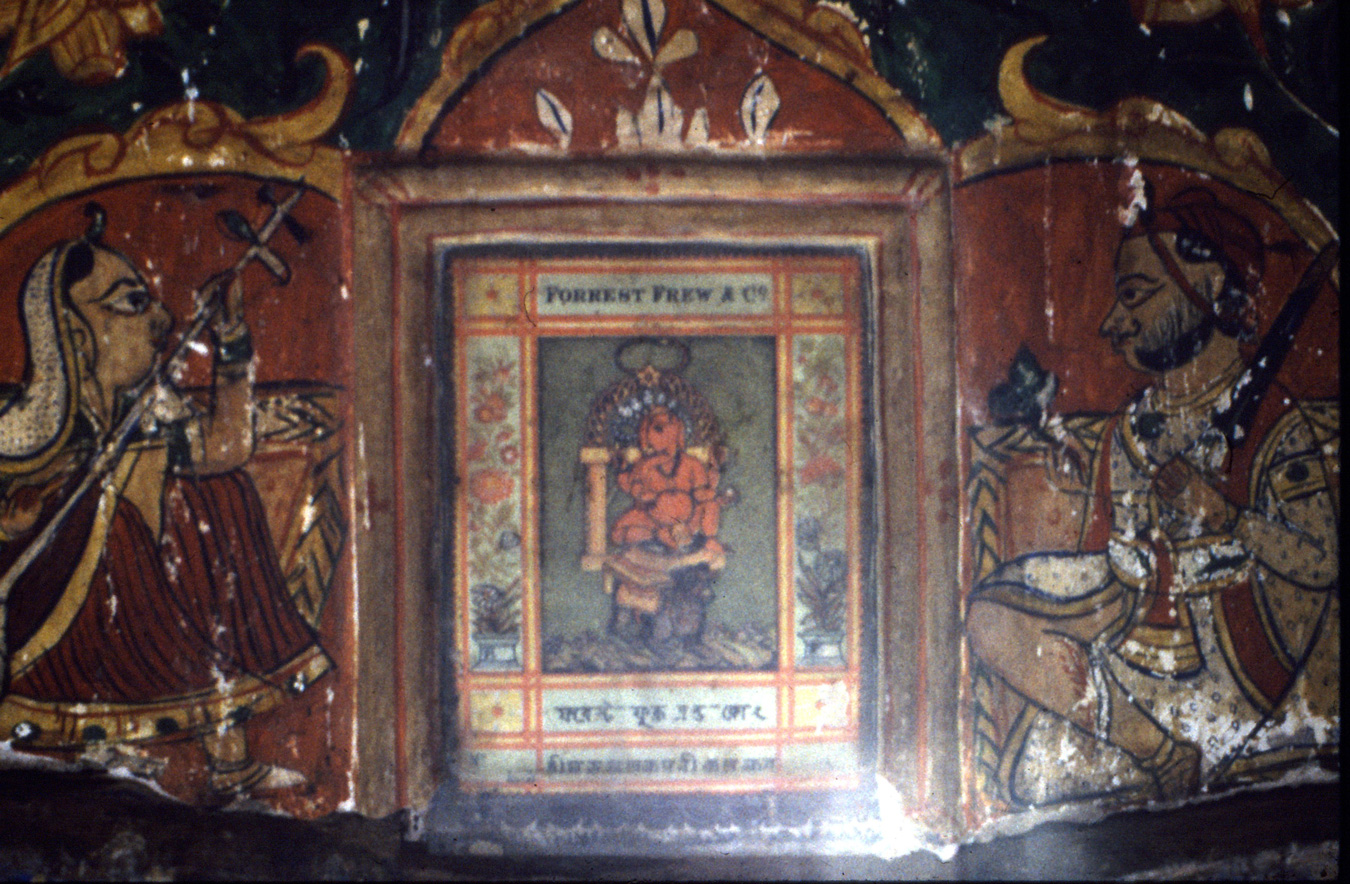

Sometimes tickets were embedded behind glass in a wall's plaster and integrated into mural paintings. Two such in Fatehpur's doomed Chaudhary Haveli advertised one 'Forrest, Frew & Co' with a pink Ganesh figure, the other 'Anderson, Wright Co' with all of Shiva's family. Both were old, matt prints suiting the 1880s date of that part of the building.

Some folk claim that the religious tickets were copied from the murals. In fact they were adapted from older Indian versions of a similar images. The evidence that tickets were copied comes from a number in the possession of painters' families which had been divided by a grid of pencil lines, making copying easier. Stencils were also used by the muralists for writing or repetitive images. A chhatri about 100m NE from Dwarkadish Temple (Fatehpur 17) in a scrap-dealer's courtyard still (2020) has unfinished camels clearly outlined in stencil dots in its dome.

The 'F W Steiner' Manchester ticket illustrated here features, sometimes reversed, as a mural on several Mandawa havelis. The best is between brackets low on the south wall of the Ladia Haveli (Mandawa 18). A man escapes hell aided by two rats, each labelled; one, 'day', is white, the other, 'night', is black - doubly appropriate since night is 'raat'.