29. Mandawa

28. Labels And Prints

November 5, 202030. The Fate of The Halsewell 1

November 19, 2020I first reached Mandawa by cycle in the late 1970s. The dharamshala outside Sonthliya gate was full as were the others: it was marriage season. At a leather-workers' shop just inside the gate they said that visiting tourists stayed in the fort. How much did they charge? They thought it was free. A couple of youths took me as far as the main entrance and I spoke to one of the baronial family. He mentioned a price for accommodation. Amazed, I said sixteen rupees was exorbitant; no one charged more than one. 'I didn't say 16. It is 60!' So I left. The youths, still waiting outside, took me back to the shop where the owner offered me a room upstairs free. The good Samaritan! I always greet him in passing. He was young then: now he's as snowy-headed as I.

After that first visit I came back often. Mandawa was only forty kilometres from Churu. Here I met one of the mason painters who had decorated the final years of Shekhawati's wall painting era. Jhabarmal Chejara invited me into his room. The walls bore samples of his work, western pictures typical of the decline, green lawns leading to a lake with swans – always two – a bird absent from India. Local folk protest that certain deities – Saraswati, Brahma – are associated with swans; but the hansa they name is a goose. He produced stencils of writing, mentioned a painter who, with each hand simultaeously, could draw two identical figures of Krishna. Born to the mason caste, he had learned to draw by copying the work of locally-admired painters.

While we surveyed Mandawa Rabu and I took a room in the haveli his brother had rented. It was owned by a friendly old widow – Maaji to us – who lived downstairs: isolated on the fringe of the town and alone in her big house, she was glad of the company. Rabu was fine, a respectable Brahmin; gradually she realised that foreigners like me weren't quite as dreadful as she had heard. Rabu agreed that, after supper each day, he would teach me the local language, Marwari. For the first three days we were very disciplined; on the fourth he fell asleep soon after eating. That became the pattern. I still remember the vocabulary of those first three lessons – angno, aalo, mori...

Prof Allchin had given us a copy of the street map he had acquired during the seminar and we started with the Fort, which was divided between two branches of the baronial family. As Castle Mandawa, the eastern section, had become Shekhawati's main tourist hotel. Several of its rooms were painted, most of the subjects labelled; there were deities about their business, events from the religious epics, folk tales and ragmala pictures – illustrations of the musical modes. Where water had damaged the plaster it was clear that they were just the latest generation of decoration; faintly beneath were floral and leaf motifs. The western section of the fort, generally locked, also contained pictures. One showed the fort with its courtyard divided by a wall separating the two families.

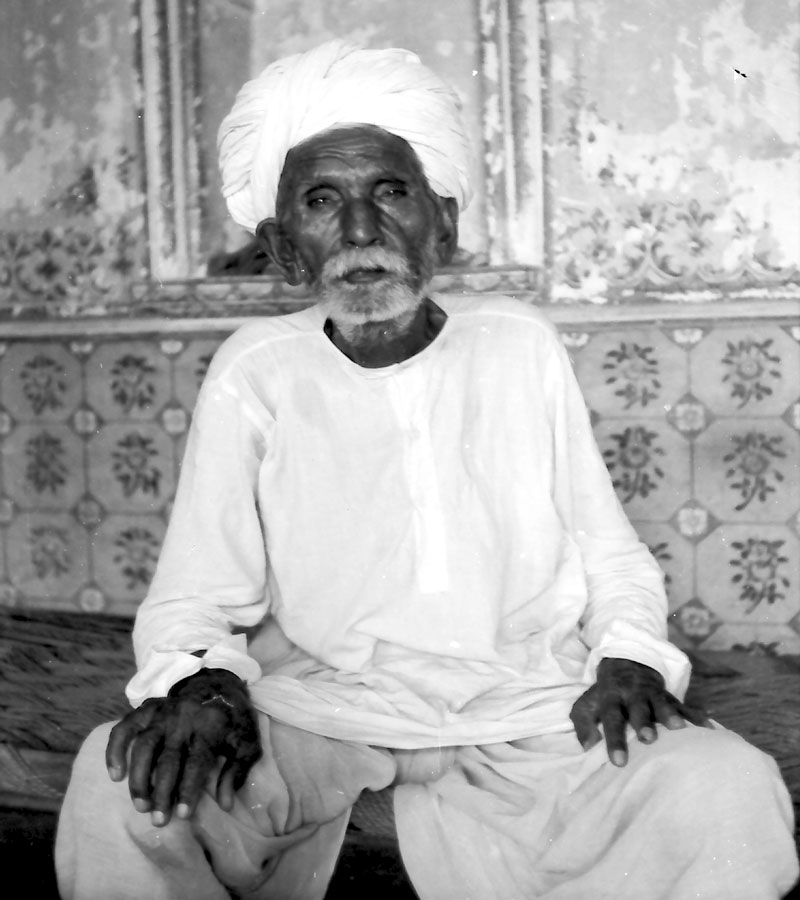

From the fort we moved to the ornate Sonthliya Gate of the town, the only one remaining, which, above its arch, had a large sitting-room laid out with thin mattresses covered with white sheeting. Here one sat, leaning against a plump masnads – bolster. Balu Ram, one of the last painters, had decorated it. The dado showed Venetian canals with gondolas, cars in a street scene and a jungle vignette from which peeps a Rousseauesque tiger. Higher on the wall were portraits of the merchant family who built the gate as well Mandawa's ruling family, including Jai Singh, who was still thakur (baron) when we surveyed the town.

As in the other painted towns, merchant-caste men moved to the East India Company capital, Calcutta, to become involved in business. Many made great fortunes, hence the buildings and their paintings. One such migrant, Nathuram Saraf, left Mandawa in the 1830s and took one of the merchant vessels that plied the Ganges to Calcutta. There he worked for a Shekhawati merchant-caste then moved to serve an Anglo-Bengali firm. He was said to be the city's first Marwari broker. Eventually he retired home, passing his business to another Mandawa man, Ganshyamdas Musuddi. As result there is a fine Saraf haveli (Mandawa 16) and a huge 1930s Musuddi kothi north of the fort and some 100m north of the main market. Every successful Shekhawati merchant has a similar tale to tell. In the 20th century it was such men who, with their business acumen, cornered half of India's industrial wealth.

Very few Shekhawati houses last two centuries; the basic building materials precluded great age. Their walls were usually made of dhandhala, light grey hardpan, a shallow mineral deposit largely consisting of calcium. At best it could be shaped into good blocks of ashlar but by the 19th century the best had mostly gone, leaving only uneven lumps. Either way, it was vulnerable to salts in solution carried up through the fabric by rising damp. Crystallising, they destroyed the footings. The usual cure was to cover the damage with cement, behind which the decay continued until the building collapsed. In towns where hardpan was unavailable the builders used brick, which proved no less prone to such decay.

In modern times, as Shekhawati murals became fashionable, another cosmetic approach to ageing has been to cover good ochre murals with gaudy artificial paints. Generally, in contrast to the original work, both pigments and painters are poor. One of the illustrations shows a small, derelict, ochre-painted haveli dated by an inscription to 1829. Had it been occupied, it might have suffered the overpainting of a similar, contemporary building which overlooks a little garden just north of a well marked in the book's map. During the survey I described it as having paintings very like those in that photograph. Now, converted to a tourist cafe, it is tragically redecorated. The exterior of a fine double chhatri (Mandawa 13) suffered the same fate although good original pictures remain in its domes.

Lockett, passing through Mandawa in 1831, mentioned an attack on the town by the Jaipur raja's forces seeking revenue. The Shekhawati thakurs, remiss in paying taxes, needed pushing. This time they held the army at bay.