34. A Pierless Bottom

33. Purbeck Stone

December 10, 2020

35. Powder House

December 24, 2020(Purbeck map with Blog 15)

I n the blog of 'Purbeck Stone' I mentioned a mystery pier. A dry valley, known locally as Pier Bottom, runs out from the west side of St Aldhelm’s Head. Until 1960 a cannon stood at its mouth, upended amongst rusty wartime barbed wire entanglements; both were defences for different wars. There is now no pier from the shore below, only the name and scattered, wave-worn worked stone, circulated by each gale, some inset with lead or bearing cut square or dovetailed sockets. Fishermen used to extract the lead for weights. Long ago I found a wrought-iron ring fixed into such lead but it disappeared until the storms of 2014 when it, or another like it, reappeared loose in shore-side clay.

There were staddle-stones, pieces of kerb, sink or roller along that beach collected ready for export, blocks, too, which were never part of any structure. Billy Winspit claimed that blocks lying amongst the reeds were left from the 18th century Ramsgate Pier job. More worked stone lay on the sea-bed off-shore. Fishermen called one such batch of rocks rich in lobsters 'Stoneboat' and always shot a pot there. It was a good place for pollack. Many boats have moored nearby; of three ancient stone anchors found off the Dorset coast two were found here. Alien stones appear, too – a Purbeck marble step, Purbeck stone fragments all from at least two miles away. Man brought them; stone doesn’t drift far.

A landing would have been convenient for loading cliff stone quarried nearby. Trev Haysom identified large mediaeval slabs of Blue Bit almost certainly from St Aldhelms Head in the floors of Christchurch Priory and Exeter Cathedral. The west side of the Head and the chapel at its tip once belonged to Cerne Abbey. Given the roads of the day, such massive stones slabs were best transported by sea. Were they dragged along Pier Bottom down to the shore? The valley, breaking the cliff line, dropped few rocks to block the beach, offering the most hospitable loading place.

The reason for a pier's construction is clear enough. Cliff stone, lightly exploited before 1700, was increasingly in demand as the 18th century advanced. The handsome façade of Wareham’s Manor house (1712) illustrates its early large-scale use. Tough, accessible cliff stone from Tilly Whim, Dancing Ledge, Hedbury, Seacombe and Winspit quarries proved a convenient source for that Ramsgate Harbour project. Aided by prevailing winds, sailing vessels carried huge quantities of ashlar and unworked block up the Channel to Ramsgate. There were two phases in that project: between June 1750 and September 1752 some 15,000 tons of cliff stone were supplied. War interrupted the trade, then from January 1764 to January 1771 another 94,000 tons left Purbeck. The pier must have been built to facilitate this trade from nearby quarries but only the valley's change of name from Coombe Bottom in 1737 to Pier Bottom indicates its existence.

When King Henry VIII dissolved Cerne Abbey in 1539, a Catholic bought this stretch of coast. It passed to George Cary, a Catholic cousin, in 1763. In those days a pier owned by Catholics would have been suspect yet there is no mention of it. Devon History Centre holds the Cary papers but none relate to Dorset lands. Somewhere a document, an aside in a book must survive. Lord Eldon bought Encombe Estate in 1807. This eventually included the west coast of The Head but no estate papers refer to the pier, no image shows a pier, no map records it, no writer, not even Hutchins in his magisterial ‘History of Dorsetshire..’, published in 1774, mentions it. Yet it was no mean project. Even today, almost 200 years after The Great Storm (if that brought its destruction), the remaining worked masonry indicates considerable investment.

Who planned the pier? Did Cary, on inheriting, set out to exploit his new estate’s cliff stone? With peace, stone was heading for Ramsgate again. Three parties might gain from a pier. Ramsgate would be assured of more stone; Cary would receive royalties; the farmer, George Cull who leased the land “... with the Quarries thereon’ would benefit. Since 1772 Cull lies in one of a row of faintly-inscribed box tombs in Worth churchyard. Another Cull tomb has a badly-decayed bluebit top probably dug from St Aldhelm’s Head.

Cliff stone interested James Smeaton, who visited Winspit in 1756 seeking material for the famous Eddystone Lighthouse near Plymouth. He chose Portland stone instead and, using an ancient method to consolidate the masonry, cut opposing dove-tail sockets in adjoining blocks then anchored them together with an hour-glass shaped piece of Purbeck Marble, 'tightly-fitting rhombs... fixed solid with well-tempered mortar' to quote a report on Eddystone. That seems an improbably rigid material. Swanage pier's 1850s stonework was similarly dovetailed together but with hourglass-shaped elm wood, better for tensile strength. Nothing remains in Pier Bottom's dovetail sockets to indicate what was used. Why mention Smeaton? He was known in Purbeck and his methods influenced many projects across the country. Why not this pier?

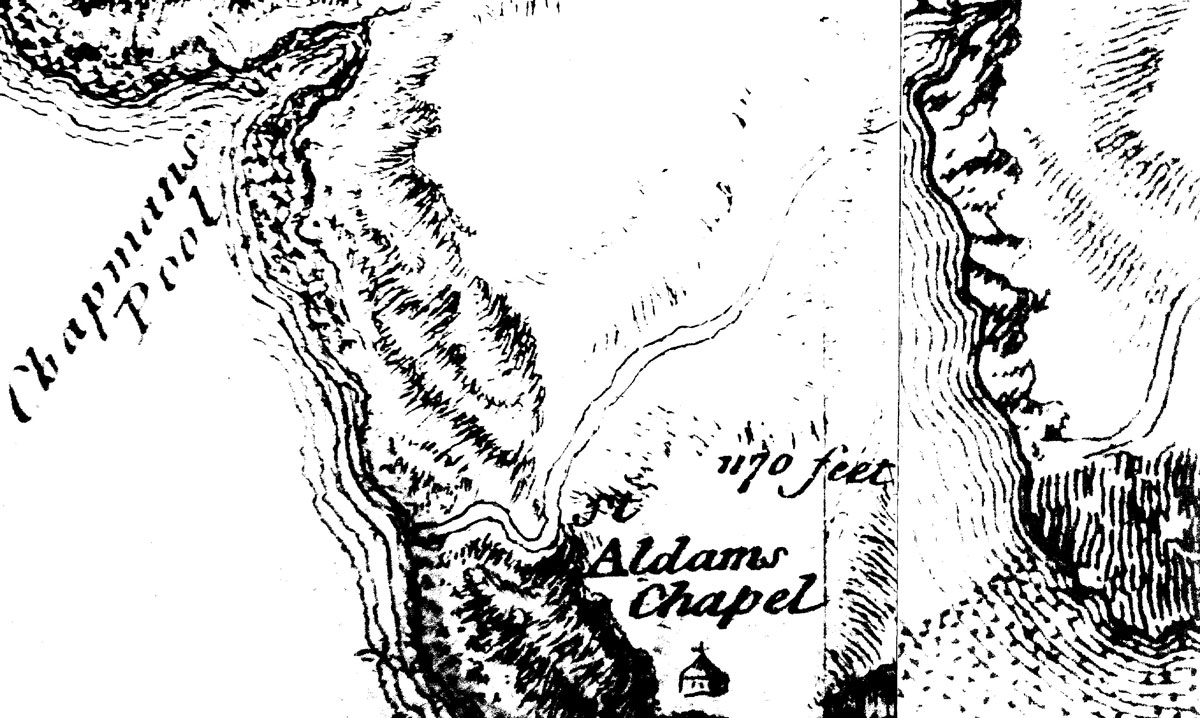

There are two maps, dated 1765 and 1798, suggesting a pier. Both show a faint track from Worth running along Pier Bottom then winding down to the shore. Originally metalled with stone rubble, the track's shadow remains clear, a shelf at the foot of the valley’s northern slope. Another, feebler shelf runs along the southern side then turns south towards St Aldhelm's Head ‘stone pitts'. A slighter track is marked running to the north side of Chapmans Pool's neck where abandoned Purbeck paving suggests another loading place.

The strongest evidence for the pier are those hundred-odd worked stones, some only exposed at low spring tide. A platform of beach pebbles set back from the shore could have been created to cover boggy ground or was it left by the sea? Whatever happened, the structure succumbed suddenly after 1798. Briefly a pier carried a small part of an important cliff stone trade then the sea, offended by such arrogance, jumbled and tumbled its stones. If it succumbed to The Great Storm of 22nd November 1824 the slackness of the current trade might explain that pier's silent passing. Whatever its fate, Pier Bottom remains pierless.