18. Puffins And Their Kin

17. Birds And Beasts

August 20, 2020

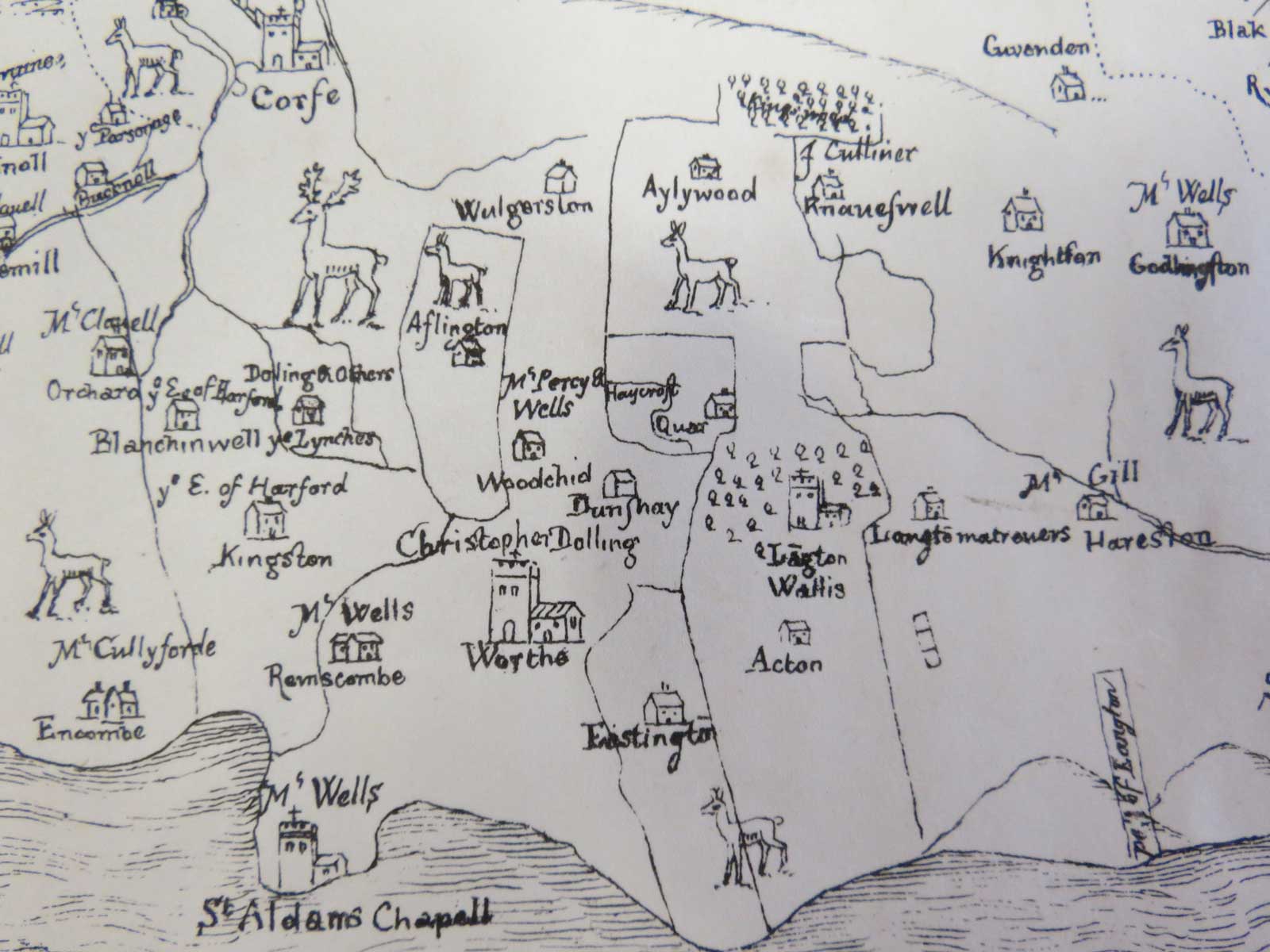

19. Dunshay: The House

September 3, 2020O f all the birds that breed in Purbeck three, puffins, guillemots and razorbills, grouped together as Auks, particularly appealed to me. Black and white diving birds, they are a northern equivalent of penguins, their small wings developed more as flippers for pursuing fish underwater than for flying. The razorbill is said to have the smallest wing area against body weight of any flying bird and all three have to beat their wings rapidly to keep airborne. Their medium is the sea, their time on land limited to the minimum required for breeding, none waiting for their young to fly properly before returning to the sea.

The puffin, most familiar, is viewed as a humorous oddity with its large red, blue and yellow beak and bright red feet. On land it is usually depicted beside nesting burrows on the grassy slopes of islands, safe from the predation of rats, which will devour both eggs and young. The Landmark Trust, as well as owning my home in Dunshay Manor, holds Lundy Island, known for its puffins; these had decreased from 3500 pairs in 1939 to a mere 5 birds by 2006. After an eradication programme, the island was declared rat-free and the puffin population has risen to some 200 pairs. Along Purbeck's coast puffins nest in dark cracks in the cliff; possibly here, too, rats have helped in their decline. On June evenings the late fifties we could count up to 85 birds near the largest of several Purbeck sites. This is now the last remaining local breeding place and five puffins was the most I saw in 2020. In contrast, the other two auks are increasing. All three lay a single egg. How do they differ?

Puffins seem to go furthest away from their Purbeck breeding place since they are the rarest out of season and, even when more numerous, rarely appeared amongst the oiled birds wrecked on our beaches. Vulnerable to oiling, they were probably afflicted too far out at sea to reach the shore. Razorbills quite often appear in winter, singly or in pairs, fishing along the coast; they form a much larger proportion of oiled auks than occurs in the breeding population, indicating their wintering nearer to Purbeck shores. They visit the breeding cliffs from January onwards. Twice I have found dead razorbills ringed as adults, both on Welsh islands, one 16 years, the other 7 years earlier. Guillemots occasionally turned up along the Purbeck coast out of season sometimes in late summer in full moult, white faced and, lacking their longest wing feathers, with mere flippers for wings. One autumn in the late 1950s a number of winter plumage guillemots appeared fishing off Peveril Point, drawn by some glut of fish, an indication that they were wintering fairly close by. They were slightly commoner than razorbills among the oiled birds. Flocks of them turned up at the breeding sites from early winter onwards, suggesting that the Purbeck birds staying in close proximity to each other at sea – or is there some trigger that calls them independently to visit the breeding site out of season? Each year we pushed back the first sighting, finally discovering that Guillemots visit the cliff as early as October. Usually these early visitors already had the chocolate brown face of breeding plumage. Both razorbill and guillemot have a white-faced winter plumage thile the puffin's winter face becomes greyer and its colourful beak sheath is shed.

Last of the three, the Puffin arrive at the cliffs in early March and lays a white egg with faint lilac markings which hatches after some 42 days. Since, in Purbeck, they nest in deep, dark crevices, we rarely glimpsed an egg and could only guess at the laying date. It was hard to see a razorbill's egg, although some laid in very visible niches so it was possible to assume by a bird's position that it had an egg. They for some 32 days. Guillemots were the most obliging; The Point at Durlston, until it fell in February 1975, gave a view onto a populous, open ledge where we could record the earliest sighting of eggs, usually on or around 23rd April, St George's Day. They hatched in some 34 days.

The Puffin spends chick takes just under 50 days to fledge while the parents feed it on small silver sandeels carried across the beak. Razorbills bring in rather larger fish and the guillemot often carries a single, large silver fish lengthwise in its bill. When the puffin chick is fully feathered its is already heavier than its parents, who abandon it. Soon hunger forces it, under cover of darkness, to flutter down and swim alone out into the ocean. Instinct teaches it to fish. What recognition, contact or relationship the growing chick has with its parents is unknown; do they part for ever, passing each other unrecognising?

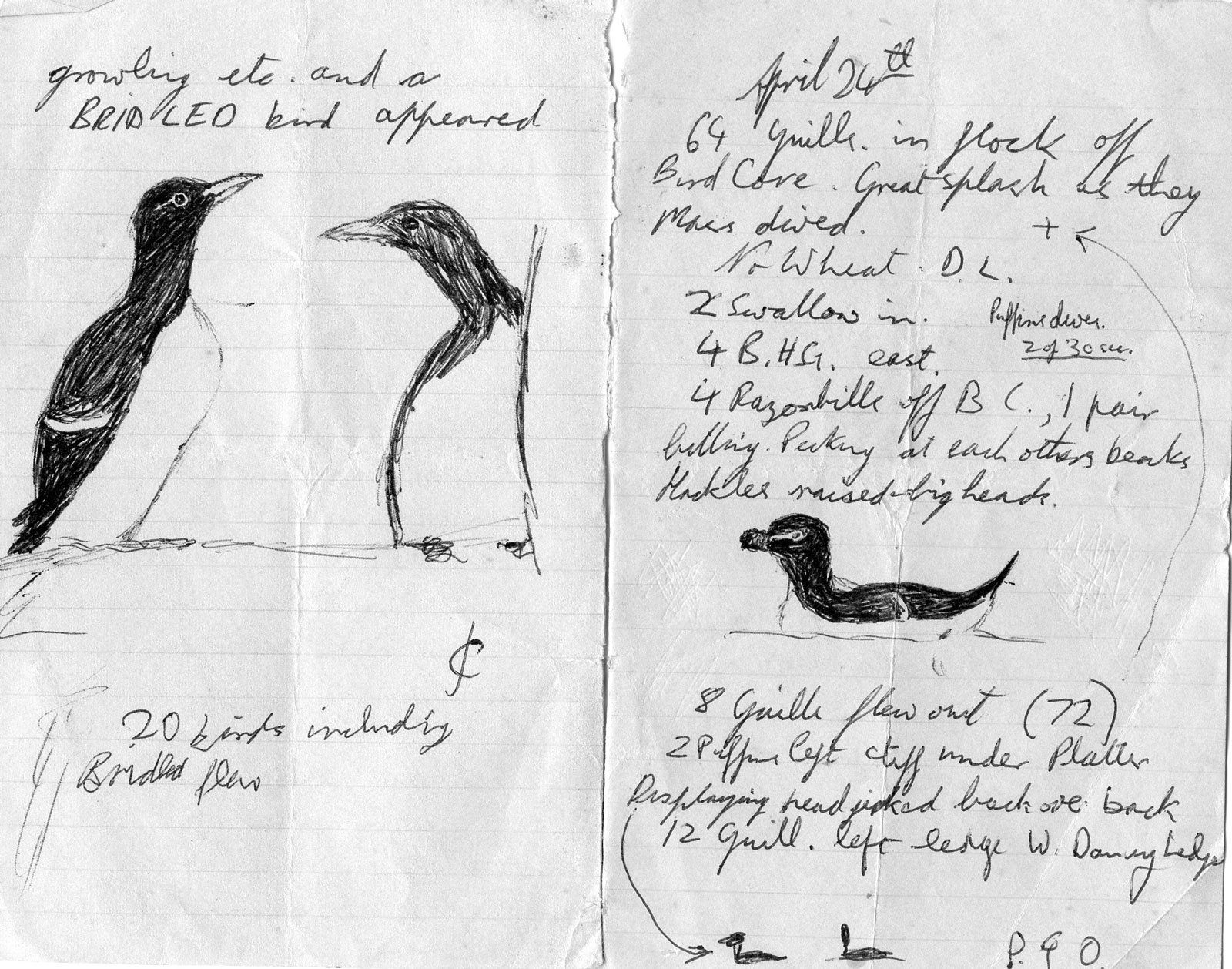

The period of about 92 days from a puffin laying to its chick leaving is much longer than that of the other two auks, c54 (34 + 20) days for a razorbill and c53 (32 + 21) for a guillemot. Both these birds encourage their chick to flutter down to the sea long before its wing feathers are fully developed. I have never seen a young razorbill jump but have watched a number of guillemot chicks leave at dusk. An adult bird sitting on the sea below the ledge becomes agitated, groaning and growling. The chick, no less agitated (and with more reason), replies with a loud whistling call. Often gulls watch the event, hoping to seize and devour the young one before it dives under water. If all goes according to plan, the chick makes straight for its parent, its father. He heads out to sea into the gathering darkness with the infant swimming desperately at his tail. I have only twice seen breeding auks on Purbeck's cliffs after the end of July, most recently when a single pair remained with their chick on 6th August 2013. They left that night. Parent and chick will stay together for an undetermined time as the chick grows and becomes increasingly independent. It will be three or four years before it will breed.