17. Birds And Beasts

16. Tanglin Cottage – The Garden

August 13, 2020

18. Puffins And Their Kin

August 27, 2020M y father was interested in birds. On his bookshelf was a first edition of the 5 volume Handbook of British Birds, published during the war and still boasting its neat paper covers. Now, well worn, covers long gone, it sits behind me. There was a beautiful volume of Audubon's 'Birds of America', too, given to him during the war by an American officer. We loved those wonderful, often-dramatic prints. I inherited his bird books and, too smart for caravan life, gave that one to my nephew, David. On the Sunday walks we called 'wetties', since it usually rained, my father pointed out various birds: I remembered.

In the mid fifties, for boys birds meant eggs and competitive collecting. But that hobby was on the cusp. The Protection of Birds Act of 1954 made collecting eggs illegal, adding a further frisson to one's collection. Laws made little difference to lively boys but the Act was born from a change in perception. In my year at school there were more boys interested in looking at birds than egg-collectors. Birds were part of a bond that tied five of us; Richard Verge, Robert Smith and I were all from Swanage, Treleven (Trev) Haysom from Langton and Patrick Birkill, a boarder from distant Tolpuddle. There was also Keith Macdonald, killed in 1957 when we were looking at birds on the chalk cliffs near Ballard Point.

Robert, Richard and I would go out bird-watching and finding nests along Ballard Down, then advanced northwards towards Poole Harbour and the lake, Littlesea. There, the beach and dunes, once practice area for the D-Day Landings, were scattered with used or half-used munitions. We stepped carefully, knowing they could be lethal. In 1956 (was it?) five schoolboys had been killed on Swanage Beach while trying to open a landmine.

We took to the south coast of Poole Harbour, particularly a little bay we called Curlew Cove on the east side of Goathorn. My diary started there on 12th February 1956: I was 12. Rereading it was distinctly embarrassing; the style owed too much to Enid Blyton and the bird species were sometimes improbable. The track there had been a Victorian tramline carrying clay from pits on the heath to a pier. From its raised embankment we could scan the shore for birds. In winter, there were many curlew, redshank, godwit, sheldduck and other duck. The occasional marsh harrier, with an appetite for birds, flew over low, causing general panic. Littlesea, fresh water and prone to freezing in cold weather, offered mallard, whistling wigeon, little teal, pochard and other diving ducks. Occasionally, wild whooper swans landed there.

Many of the waterbirds that fed in Poole Harbour flew out to sea each evening to roost, returning in the early morning. We sometimes cycled to the harbour mouth in the morning or evening to count them. Habits change and birds no longer make that little migration.

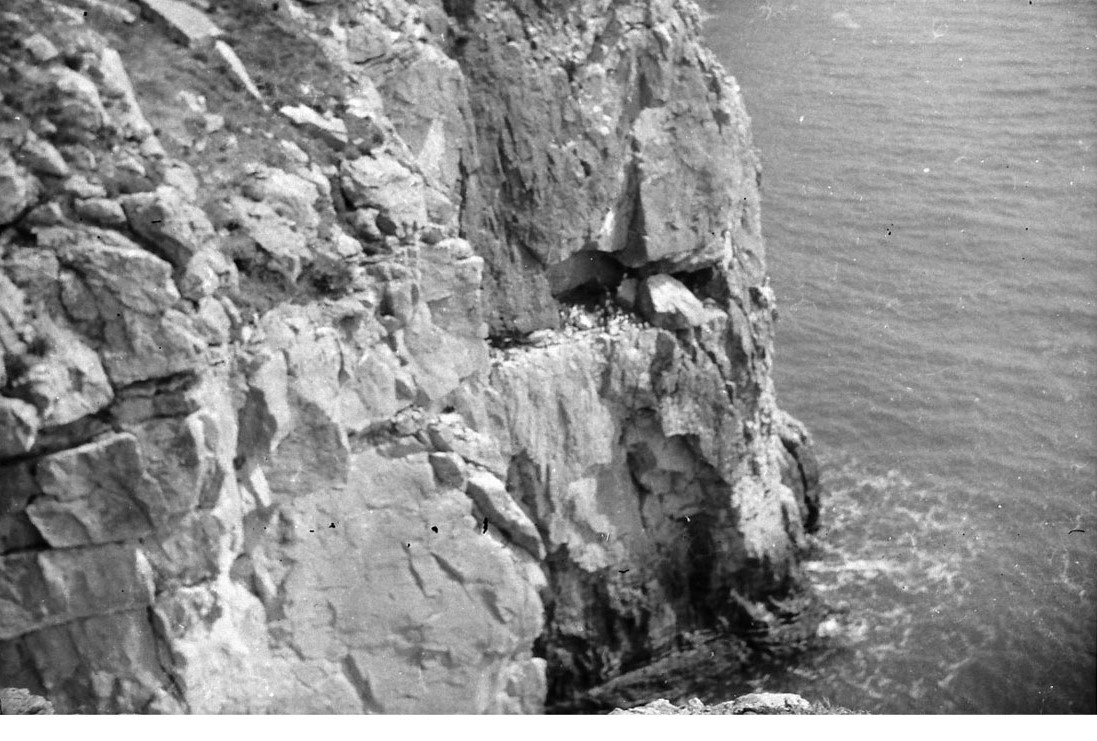

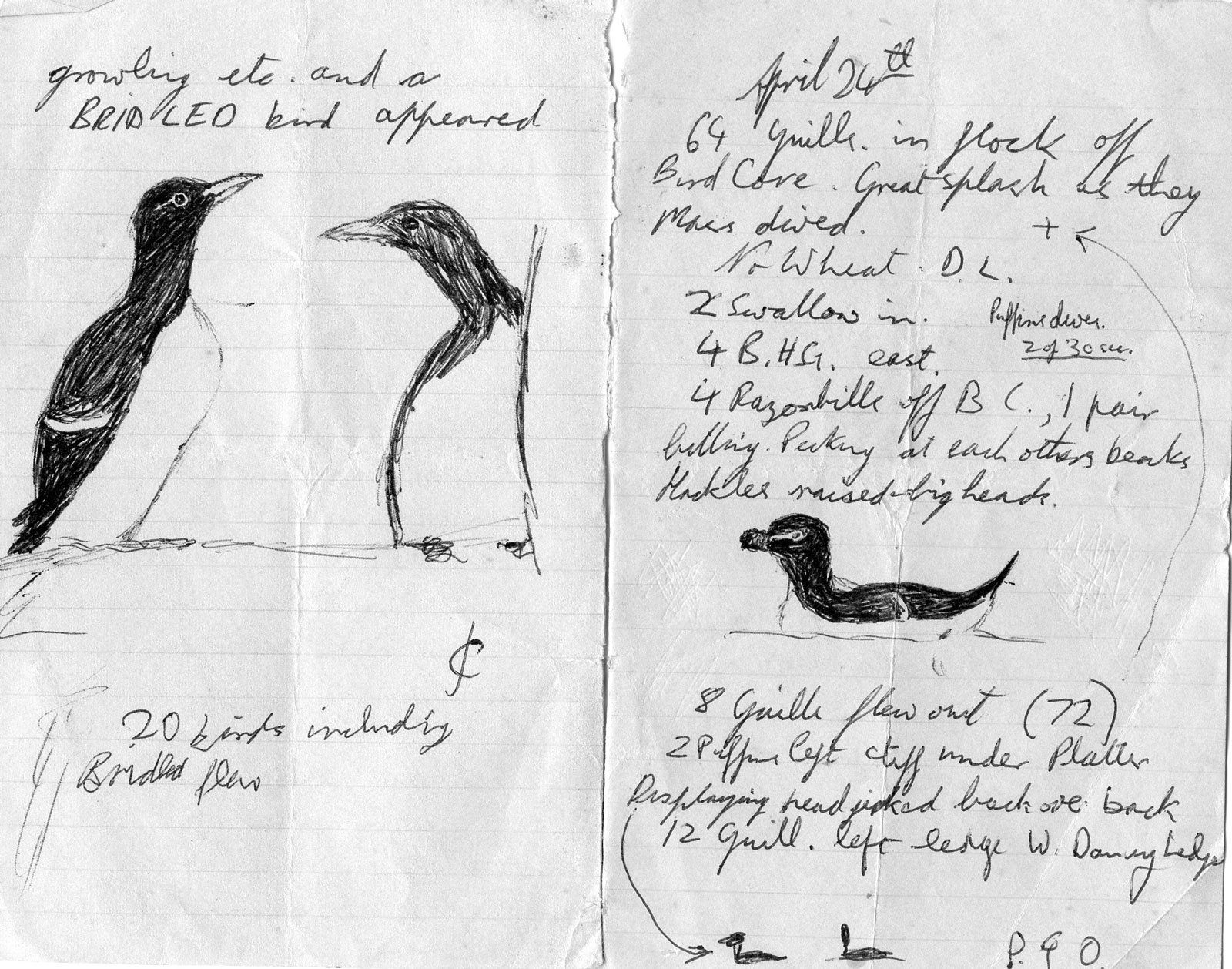

In spring and summer our attention turned to the cliff birds. The best place to watch these was Durlston, immediately south of Swanage, near my primary school, Hillcrest. There, on school walks, I first saw guillemots. Later, independent, we'd cycle there of an evening and, following the clifftop, cross a low wall onto The Point, a clifftop projection giving a good view of the largest Guillemot ledge in Purbeck and of kittiwakes and razorbills. We could see puffins flying to their chosen crevices, always hoped to see one land at a burrow on the grassy slopes as in illustrations. They never did; perhaps rats had discouraged them from such accessible places. Curious fulmars would glide silently past then, returning, take a closer view of us. Adult walkers, politely ignored, looked down from the path to warn that our perch was dangerous. It was. Having served our purpose, The Point fell and survives only as large rocks in the sea below.

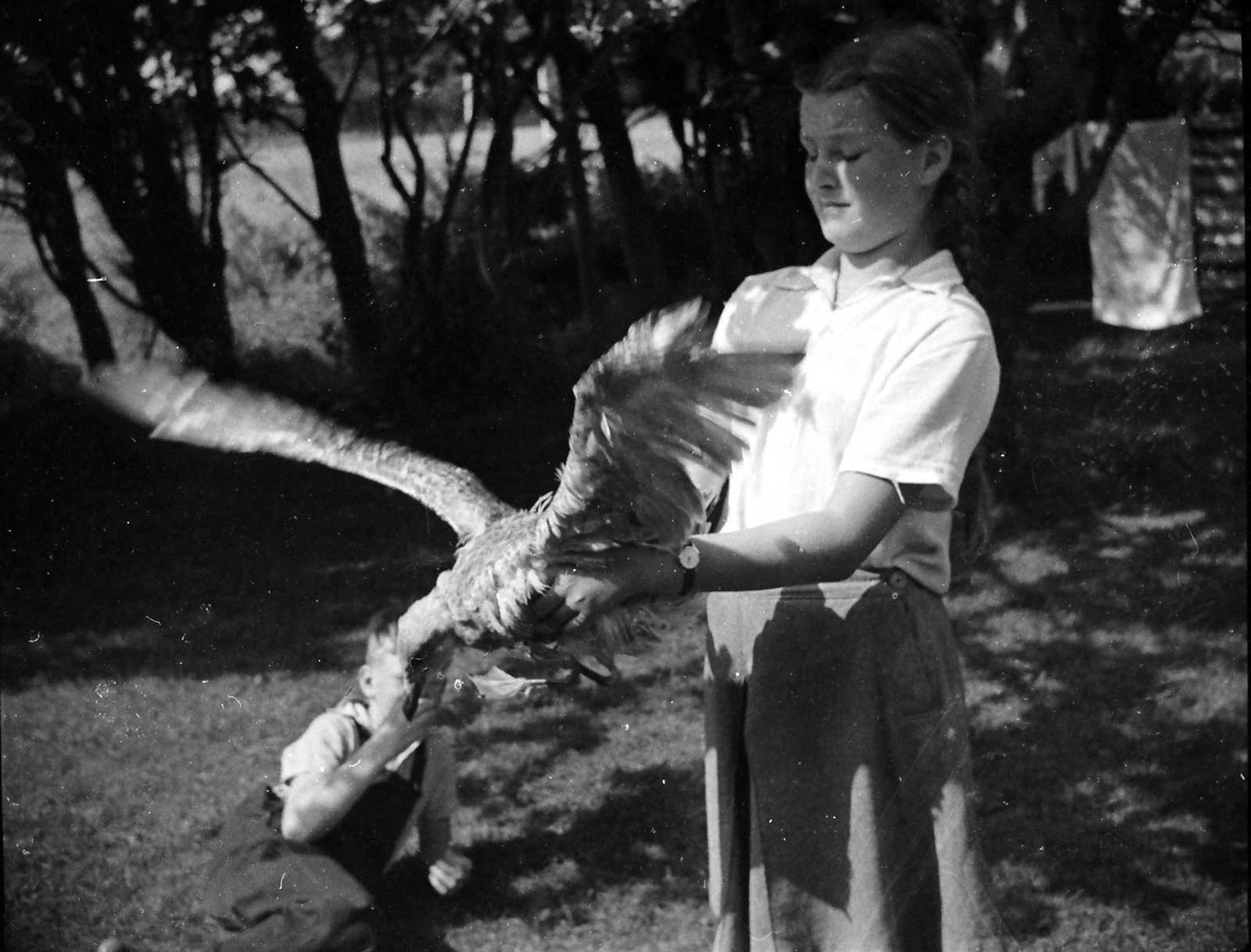

In early 1957 oiled birds were turning up at Chapmans Pool. I cycled there to meet Trev and Macky, coming home with an oiled guillemot in the front of my jacket. After that Trev, Macky (who lived halfway to Langton) and I generally spent weekends together. Trev was keen on peregrines. I liked the auks. Our rivals were egg-collecting boys with their ropes. We needed no ropes since our climbs were to find the best viewpoint not to reach precarious nests. At a few easily accessible-sites we could return the gaze of a sitting puffin. Eggs were a temptation, especially guillemots', large and tapering, varying greatly in colour but usually a wonderful green. A compensation for being summoned to the headmaster's office was the confiscated one standing on his windowsill. I took Herring gulls' eggs to eat, which seemed fair since they ate other birds' eggs and young.

The master egg-collector in Purbeck was Raymond Newman, later landlord of The Square and Compass. He could reach anything, taking full clutches of peregrines' and ravens' eggs as well as those of seabirds and all manner of land birds. No one could deny his reputation as a daring climber. Later, after his climbing days were over, when I became a regular at 'The Square', we discussed his forays and he sent me upstairs with his young son, Charlie (now the pub's owner) to see his collection. In return, I gave him a poor photograph, taken from the shelter of bushes, showing him climbing to a sparrowhawk's nest.

With time, although the interest in all birds remained, extending to cover Indian species, my focus was on auks – guillemots, razorbills and puffins. There was one stretch of cliff, a sample of the whole, where I watched them. It had no puffins – by then their extinction was well advanced – but there was one ledge with some 20 guillemots and a single razorbill site. Now there are three guillemot ledges, a fourth developing, and the razorbills increase. The peregrines weren't wiped out by egg-collecting: it was insecticide – dealdrin – which saw to them. When it was banned they soon revived. Meanwhile, oil spillage at sea (today replaced less generously by palmoline swilled out from tankers) did far more damage to seabirds than egg-collecting ever could.