66. Gwalior’s Fort Then South Into Bundelkund

65. To Agra’s Mughal Sights, Then Southwards

September 1, 202267. Bundelkhand And Datia

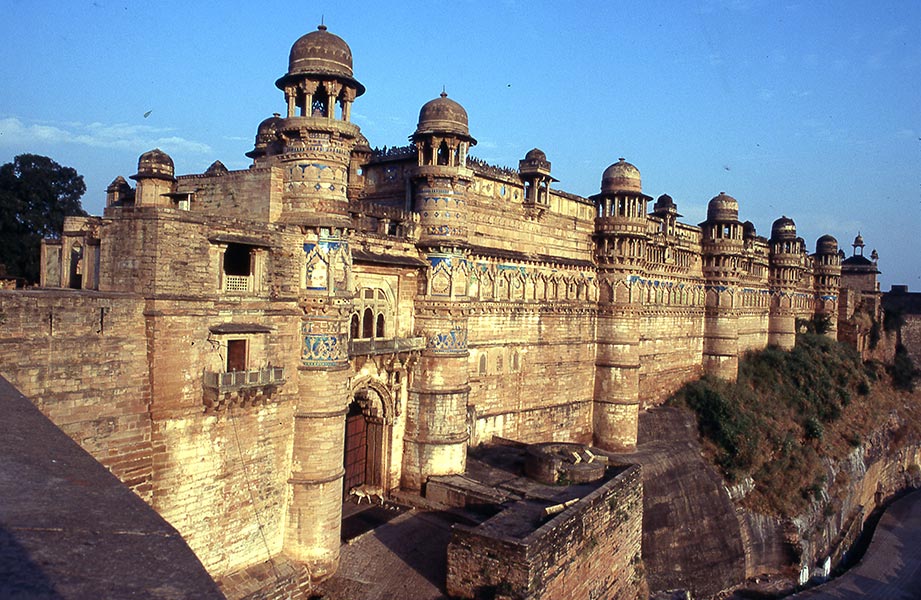

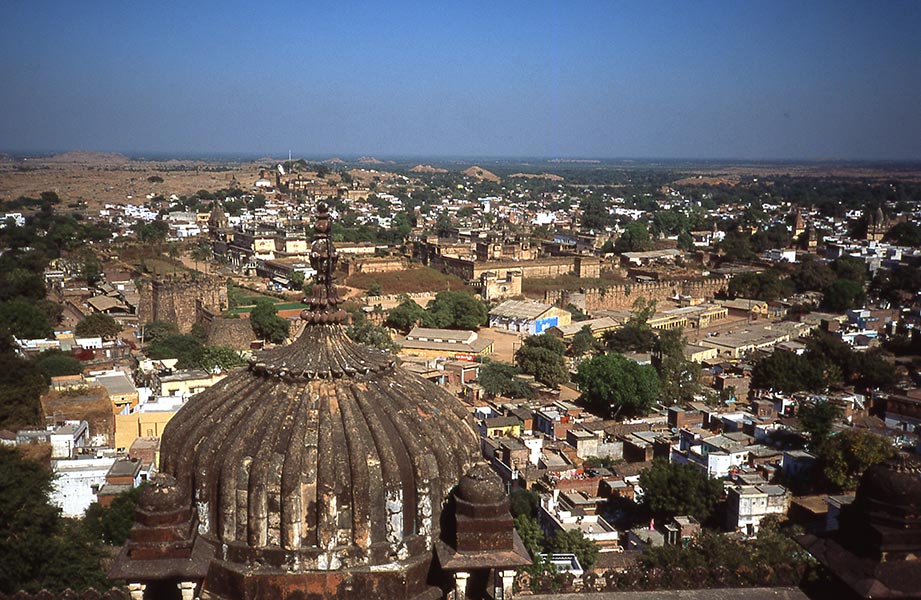

November 3, 2022I n the morning, I pushed the bike up a winding, cobbled track into Gwalior’s fort. The 15C palace, Man Mandir adjoining the gate, made stunning by coloured tiles, impressed Babur, the first Mughal Emperor when he passed this way. He praised it in his memoirs. Passing modern buildings bright with bouganvileas, I cycled to the fort’s south extremity overlooking the city. Below, white-rumped swifts and red-rumped swallows fished the air for flies.

There are several ancient derelict temples within the fort, the oldest (8th century) being crowned by a barrel-shaped structure resembling a South Indian goparam. Another later pair are more typical; the larger, heavily carved, is tall and airy with four massive pillars, aided by twelve smaller ones, supporting its dome. On a shelf in its contemporary neighbour, lay a boy, large eyes ever watchful. Sitting opposite, smoking a beedi, I wrote. A short, dark man joined us. He had flat features, a straggly beard and long, faded dreadlock hair. His face was made up as a mask, black about the eyes, a strange scarlet design on his forehead with some bright bindis stuck about it; one kept falling off. Carefully replaced, it fell again. He wore a woman’s green bodice, much the worse for wear, decorated with gold thread and sequins, and a long, loose green skirt. On his head was a little, stiff cap, such as north Indian infants wear. Carrying a staff and a tin for food, he looked ageless.

With surprising agility, he sprang up beside me, then signaled for my notebook and a pen. His words remain in the book, large, coarse devnagari letters: ‘Which is Gwalior?’ ‘Where is Morar?’ ‘Show me Kanpur station.’ ‘Lashkar?’ ‘Where do they hold the fair?’. Interested, the boy joined us, pointing out the things he wanted to see. He followed what we said. Was he pledged to silence? Satisfied, he jumped down and left. I returned to the palace. The tilework is blue, green and yellow, the rooms small and dark, ceilings low and walls pierced by geometric lattice-work windows. Alas, the fate of rebellious Mughal princes! Royal blood unshed, they were imprisoned here, fed on post – opium husk – until, losing all interest in food, Death brought relief.

At dusk, I descended into the city and, inspired by a poster, went to see ‘Patton’ at Chetra Talkies, leaving the cinema alongside several transexual hijras in full regalia. The Muslim month of Muharram: next day was Asura, the Shia day of mourning for Hussain. In the evening I walked into the city centre, hoping to get caught up in a frenetic chant of ‘ya Hussain!’, ‘Ya Ali!’. All was quiet. Perhaps Gwalior has few Shias. I returned, moonlight on the fort, conscious that Indian solitude can be especially lonely. An empty day had ended in a small, quiet, tea-house. A youth sat at the next table. When his friend joined him, sharing the same chair, he put his arms tight around him, held him close. The friend pretended to complain but he whispered something in his ear. They smiled. I felt expendable, intrusive.

Quitting Gwalior around midday, through rolling, scrubby land – good for dacoits, not for agriculture – I cycled into more fertile land. In a tea-house, feeling the heat, pouring sweat, folk passed me a chelum. ‘Have a puff’. I refused, continuing southwards, quickly exhausted. I hadn’t eaten much; the wayside sabji and roti wasn’t enticing. Into the Bundelkand region and some way short of Datia, a slow puncture developed. Pedaling like hell, stopping at intervals to pump, I entered Datia past a temple by a tank, a striking hilltop palace. This town seemed a good idea. After bathing at a dharamshala, I joined a group of travelling actors putting up there, come from Mathura to perform Ramayana stories. The leader, with good English, declaimed the lengthy story of Narad, who had decided to fall in love. Having asked Lord Vishnu to make him handsome, he went to the palace where the goddess Lakshmi was choosing a husband, but in punishment for his arrogance, Vishnu had given him a monkey’s face. Try as he might to catch Lakshmi’s eye, she went off with Vishnu. Then he saw his reflection in a pool.

A man, whose father was a refugee from Pakistan, took me home, where his wife, more fluent in English, talked of her highly-placed relatives. A retired smuggler from Bombay arrived and regaled us with tales of his heroism, motorbike, bungalow. Bored, I left to attend the interminable drama, modelled on Bollywood with exaggerated action and dialogue and a pair of comics with funny voices. The current episode told of Ram’s first glimpse of his beloved Sita. India is so unlike Britain. Terribly handicapped children are not hidden away but remain in the family, part of society. Crouching amongst the audience was one such, a dark youth with a tiny head, bulging eyes and long, thin arms. He stared, making me uneasy. Joy and sorrow are simply deviations from life’s norm; however that fellow might think, his life is subject to the same fluctuations. This much of his world, if little more, I can comprehend.

A nervous young teacher asked me to address his college. Refusing, I agreed we meet next morning. That night teemed with bedbugs. They are said to steer by body warmth, dropping from the ceiling on their victims. Doubtful, I watched one align itself above me, then fall - and crushed it! Next morning, giving up on the teacher, I breakfasted in the street. The only white-skin in Datia was easily traced, so he turned up and showed me the town. Finest was the 16th century palace built by Raja Govind Singh, friend of Selim (fated to become emperor Jahangir), who killed Akbar’s amanuensis in a fit of peek. It is decorated more modestly with coloured tile than Man Mandir and its doorway led into a darkness penetrated by isolated shafts of light. The roof looked out past a ribbed dome of the palace to the ruins of a subsidiary building where a decorative tower still stood, another is only a stump. Grass grew thick and brown over the walls. Behind and below women washed clothes on the steps of a big jheel with the temple beside. The town was hemmed in by low, dry, rocky hills.