3. East Against The Trend – 1

2. The Returns Of A Non-native

April 23, 2020

4. East Against The Trend – 2

May 7, 2020T he first year exams, a harsh thinning of the crop, would spit out half us students. There had been too many distractions; best anticipate failure by going abroad. In the mid sixties sensible youths went west, working a free passage to Canada or the States: there lay money. I took the ferry to Belgium then turned east for Athens, hitch-hiking - the one talent university had taught. The war, petrol rationing, soldier heroes bound home on leave had made hitching an accepted mode of travel. With peace, soldiers were fewer; their place had been taken by students in their teens, early twenties. Some bore a nation's flag, others, a placard with a destination. I had neither. You stood by the road raising a thumb at each passing vehicle until one stopped and the door opened into the driver's private space. It was generally a man, alone, fairly young, perhaps not going far but, in stopping, he became a friend. The police were hostile, quick to hassle; we were ragged, free, currently poor, but with prospects.

So, I was whisked across Europe. Youth hostels provided cheap accommodation, although some expected an hour's domestic work on top of the fee. Most of us carried a sleeping-bag, preferring to find somewhere free; money was for food, fags and booze. In 1964 drugs were not yet an issue: even The Beatles were new. That summer was hot. Abandoning the shimmering road, I'd linger at noon by some cool stream. Across Germany into Switzerland – Eschenberg; was that where Sherlock Holmes fell to his first death?

Austria was like home. My father, in the army, had been posted there with the post-war Occupation force. We kids loved it - fishing, skiing, exploring the forest and swimming in the river. They put out black banners when the King died. I reached the first Austrian town, Feldkirch, towards dusk, rain obscuring the mountains, ominous flickers. It became a scene from a Disney cartoon, great blue-black clouds rolling down, vivid lightning, amazing consecutive flashes lasting seconds. Peaceful stillness disappeared into vicious, dust-filled squalls bending the trees. This was an indoors night. Kids on cycles rushed past ignoring requests for the youth hostel.

The wind roared, blue light illuminated then abandoned the streets. The first huge pattering drops, smelling of damped dust, gave way to a torrent just as the hostel appeared. A shared room with a Canadian, who had been exploring Europe for several months. Pleased to be back in Austria, I booked two nights, a day to enjoy that sense of home, a schinkenomlette, climbing into the hills, eating wild raspberries and meeting an elderly gentleman, his conversation distorted by lack of teeth.

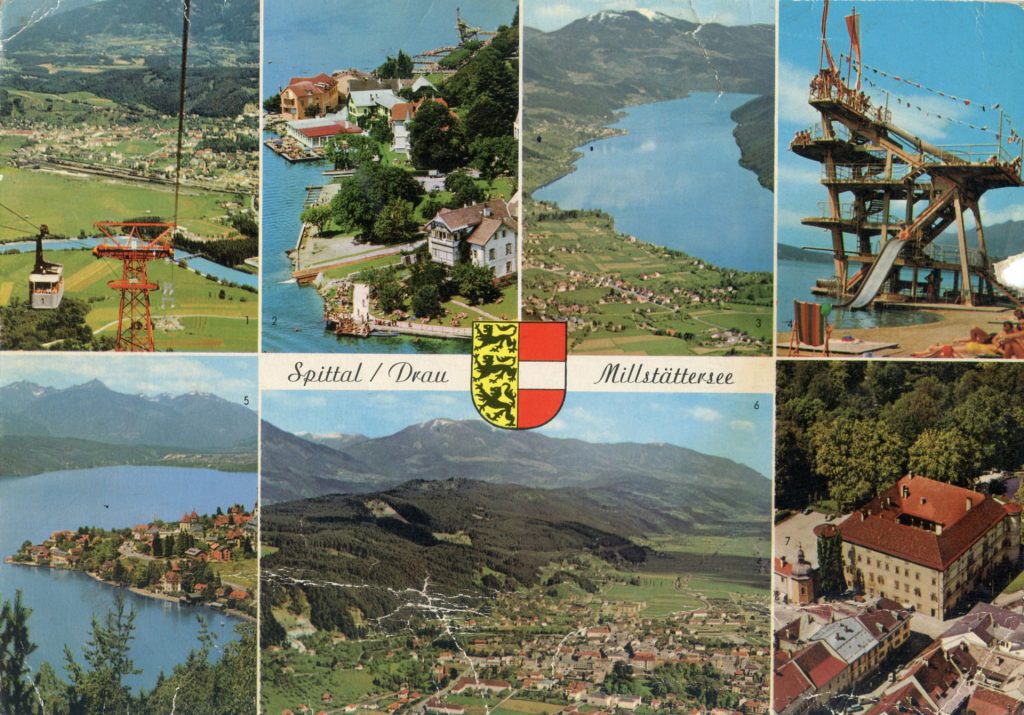

Along the narrow handle of the country were black scrawls, 'Freiheit Sud Tirol', still resenting Italy's acquisition of South Tirol after the First War. A night at Auntie Kathe's – no true aunt but a maintained friendship: my parents were good at keeping friends. In Spittal, the next town, the youth hostel lay beneath the high school, opposite our old house. Dr Schreiber provided supper. Where was my friend, Manfred? Married and gone. I walked past my school, over the river still with its dippers. The encamped D.P.s – 'displaced persons' – left by the war had long gone, found other homes.

From Villach, after chucking the rucksack on the back of a vast truck, I eyed the mirror in case it fell off along a winding, climbing pass. Over the frontier Yugoslavia, always a fragile state, stretched all the way to Greece. No driver described himself as Yugoslavian; all were from fragments of the land - Slovenian, Croatian, Serbian, Bosnian...

Trains were cheap there so, diverting seawards, I took one to Split, a first Turkish coffee by the clear aquamarine Adriatic, bright fishing boats, moored against the quay, staring through carved, painted eyes. The coastal highway southward was under construction; 20,000 men must finish it by May. An engineer dropped me where the track was blocked by over-enthusiastic blasting. Crossing the rubble, I stayed in Ploce with two young Serbian workers before taking a night train next to an old man with two tortoises. A student eagerly offered a diversion via his flat in Zagreb. Wrong direction. Instead, to Sarajevo, a quiet tourist town with cement footprints where Princep shot a prince, minarets outnumbering spires, a first taste of Turkish cuisine and a cable car to a pretty panorama. Thirty years later most was smashed, many killed, as Yugoslavia fell apart.

Belgrade was plain, expensive and uncapital, Skopje chaotic after the previous year's devastating earthquake. The station clock still stood at 5.20. A soldier artist's wife put me up amongst his beautiful paintings of a dead kestrel, storks. Then on to Tito Veles and a dream lift with an American couple all the way into Athens. The youth hostel gave free accommodation to those who would chop vegetables in the kitchen. A good deal, I joined Tony and Werner chopping. We swam near Piraeus with an English couple. In the sea she flirted with a handsome Greek while her red-head boy-friend, trying to intervene, was badly sunburned. While he recovered, she played the field until kicked out of the hostel for snogging innocent me.

In London I'd left a stamped letter, addressed to Athens, with a friend for my exam results. It never arrived – the expected failure! So I was free. Both guys in the kitchen suggested I join their onward plans. Tony was sailing to Israel, £18, to join a girlfriend on a kibbutz: dear and unpromising. Werner would take the ferry to Greek Chios, then Turkey and beyond - £1.50. No contest! I left with him, Greece and Turkey threatening war. As the ship chugged across the Aegean a ceasefire was agreed in time for the ferry onwards to Turkey. Werner was German, a couple of years older, completing a philosophy degree. What was philosophy? What was Turkey like, what the customs, costumes? Ignorant, I'd learn...

*

to be continued....