2. The Returns Of A Non-native

1. A Train For Pakistan Leads To Painted Shekhawati

April 16, 2020

3. East Against The Trend – 1

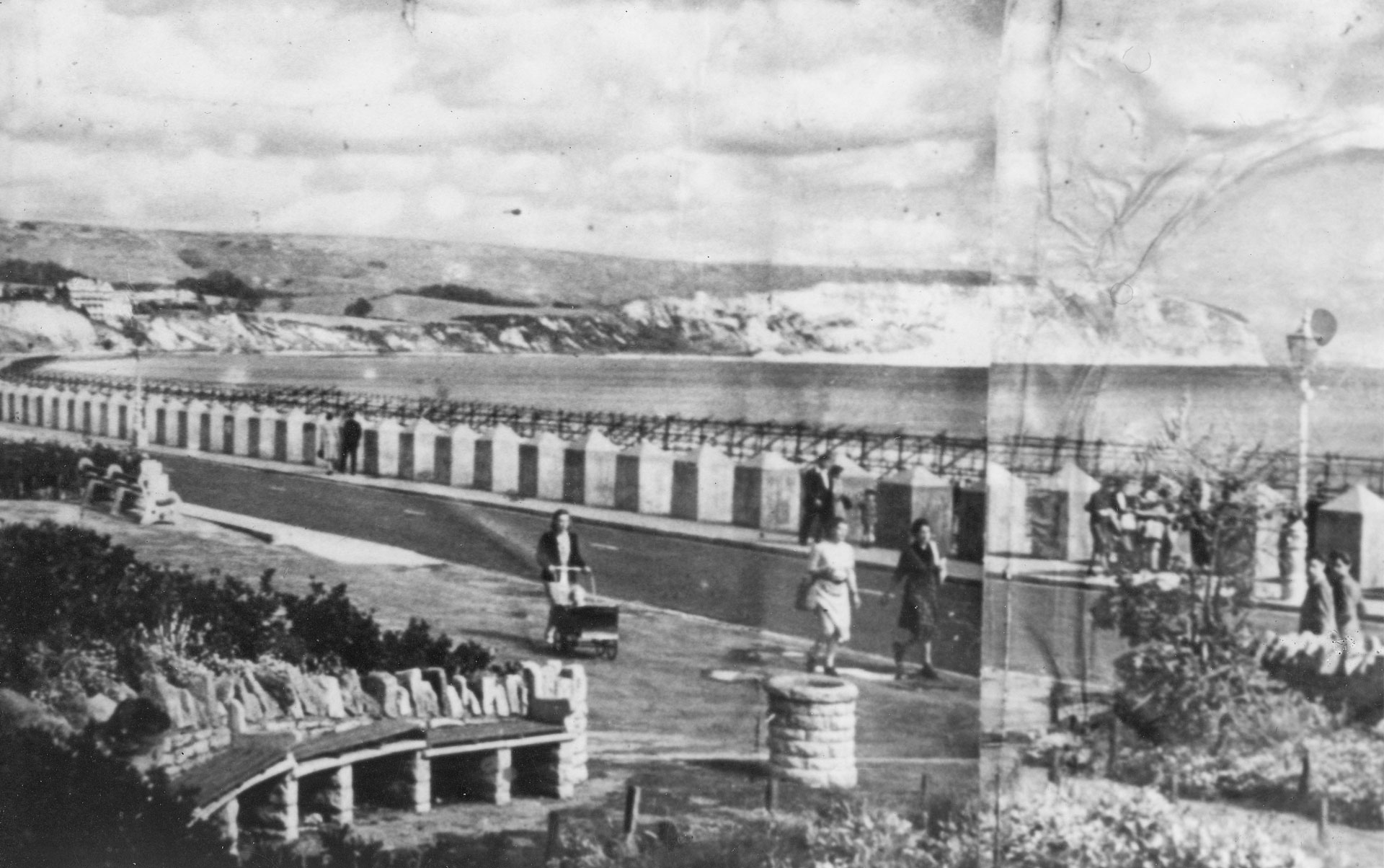

April 30, 2020A peninsula, marginally not an island, the Isle of Purbeck lies in the middle of England's south coast. Its central spine of chalk forms an east-west ridge with a fertile valley running parallel, its southern side rising onto a limestone plateau. This upland falls abruptly as cliffs into the sea. North of the spine heathland descends gently to the banks of the river Frome and its estuary, Poole Harbour.

The limestones provided a rich source of stone since Roman times, the uppermost bed, blue-grey and richly fossiliferous, known as Purbeck Marble. It was an important decorative stone, used inside churches for fonts, tombs, effigies, pillars and narrow shafts, reaching peak popularity in the 13th century.

Purbeck has two small towns, larger Swanage, long a fishing and stone-exporting port, and Corfe, once focus of the marble industry, its castle dominating a pass through the ridge. The railway came to both in 1885, terminating in old stone-built Swanage, built on a brook opening into the south corner of a sheltered bay. From then onwards the town developed a summer tourist trade and a red brick suburb, 'New Swanage', grew up, following the road north to Studland. Many of its villas became guest houses, one even a Grand Hotel overlooking the bay. My grandmother bought one, Tanglin Cottage, too modest to hold guests but large enough for a family.

In confidence, I wasn't born in Purbeck. A native needs nativity. When people ask, I field the question neatly: 'Born here? I was conceived in The Ship.' That's a pub in Swanage High Street. It's true, but I was born in Farnham, Surrey. My father, a soldier on leave from the War, took my mother for a holiday in Swanage, and the dates fit. Hitler must have suspected something: soon afterwards, The Ship was damaged by a bomb.

My mother kept a baby book for each of her first two children. When the third and fourth arrived she had better things to do. Mine is 'The Little One's Log: Baby's Record.' by Eva Erleigh, Marchioness of Reading. A touch of class! The move to Swanage is ignominious: '19 months. Ilay copies almost everything we say & even uses quite long phrases i.e. during mopping up operations 'Don wuyey – din din soon!' Still filthy! Heaven knows when he'll be trained. Unfortunately a tummy upset on removal to Swanage spoiled his much-improved habits! He is a bit temperamental at present – works himself into hysterical furies from which he can only be drawn by a sharp slap.

'After the war, in need of a home, my parents bought Tanglin Cottage. Both from mobile, military families, they met in Hyderabad, children of parents married in India, one in Bombay, the other in Naini Tal. They could hardly have planned better: the house was only a couple of hundred metres from Swanage Grammar School, where all four of us would study. It served as a very happy home.

We had differing interests. Anthony, keen on sports, the responsible eldest, joined the navy. Libby (Elisabeth), also good at games, spent most of her career teaching in California. Charlie, the baby, bright and naughty, more interested in girls than studies, went to Australia on the £10 scheme. That fare was only if you stayed more than two years, otherwise the full cost must be refunded. He stayed. Starting as a bricklayer, he launched his own firm of lawyers.

A country boy in a marvellous environment, inheriting an interest in birds from my father, flowers from my mother, I was lucky: there were other boys with similar interests. Wildlife implied exploring the countryside. Purbeck offered everything – chalk downland, heathland, muddy estuary shores, streams and small rivers, lakes, chalk and limestone cliffs and sea in all directions. My best friend, Trev – Treleven – whose father owned one of the stone quarries, shared the enthusiasm for birds.

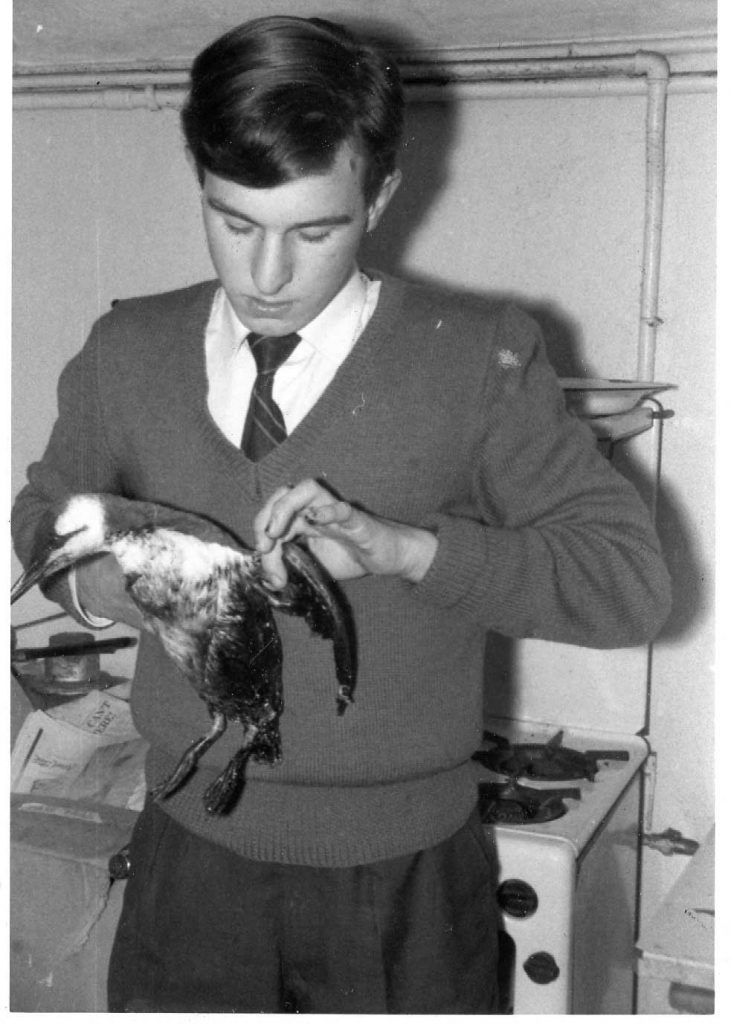

With two other friends, Robert and Richard, I looked after sick and injured creatures. There was no shortage: most were victims of man's carelessness. After unloading their cargoes at great European ports, tankers would wash out their tanks into the English Channel, a busy sea-way, the thick waste oil killing thousands of seabirds. Most were penguin-like guillemots, razorbills and puffins. We took up catching and cleaning them; each ended with a medal 'For Kindness'.

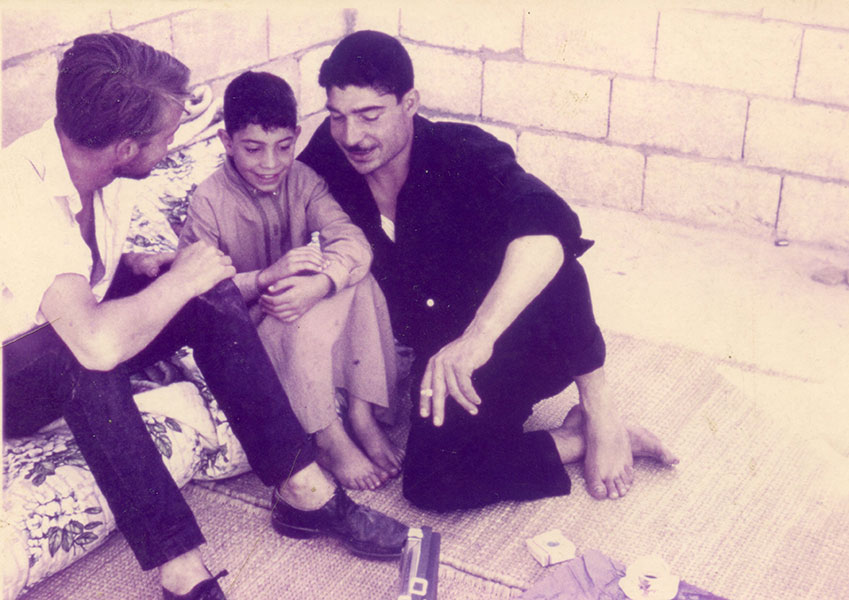

A career? Earning just sufficient to do exactly as I pleased. A short stint on Brownsea Island in Poole Harbour, as assistant warden naturalist, then, armed with a degree in Zoology and Geology, proving a poor teacher. The travelling began, financed by waitering, cutting stone in Trev's quarry then writing and photojournalism. Starting in England, I advanced into Europe and graduated to the Middle East – Turkey, Syria, Palestine, Iraq and Iran, then beyond to Afghanistan, Pakistan, India and Nepal. Soon I was commuting overland between Purbeck and the subcontinent. Purbeck remained home; someone always helped me with a place to stay – an empty cottage, another awaiting repair, a caravan in the quarry.

Finally, newly returned from India, it was proving particularly hard time to find somewhere when a friend suggested Mary's caravan. A sculptor, Mary Spencer Watson held Dunshay Manor in the middle of Purbeck. She was out when I called, but a school friend living on the estate indicated where the van was: 'I wouldn't let a dog live in it!' But Mary was agreeable: the local Council would object, 'So your official address is The Manor, mine The Studio.' She died in her nineties, leaving the estate to The Landmark Trust, me with it.

What of that overland commute?