51. MidSummer

50. A Proper English Spring

June 3, 2021

52. The Weymouth Track Again

August 5, 2021Purbeck Map Blog 15

M idsummer Day has passed. In Purbeck, everything becomes better, warmer, greener, more flowery day on day until that watershed is reached; from the summer solstice onwards it is all downhill again. There is a slight air of depression. Spring hauled us out of the cold, short days, the gloom of winter. In May and June everything goes mad. Rain, coupled with the warmth of a rising sun, sets the plants into extreme growth, dressing the skeletal trees, blocking footpaths with tall grass, nettles and thorny brambles. Vegetables flourish; so, too, do weeds. From the peak of the sycamore tree, the song thrush shouts its repetitive phrases, dominating the softer songs of blackcap, blackbird, even that of the tiny, noisy wren. Having survived the onslaught of large, slimy slugs, seedlings begin to shape into baby vegetables. Bumble bees and the honey bees from Tim’s hives are busy carrying pollen between flowers, fertilising the broad beans so that their pods begin to swell. The cabbage white butterflies have already produced caterpillars to ravage the broccoli; I fight them by hand, rejecting poison sprays. There are already lettuces and spinach to eat. This year the plum tree is more barren than usual; late frost and unseasonal gales destroyed what blossom escaped the beautiful bullfinches.

June 21st rarely passes unnoticed. I’d planned to go to The Square and Compass that evening, but it proved a day of grey, persistent rain. One summer Trev noticed that on Midsummer eve, viewed from a prehistoric tumulus, as the sun sank it appeared to slide down the slope of a nearby hill. Its trajectory is no coincidence; someone planned that mound with the knowledge. How many other such forgotten markers remain ignored in a world where other science has made them redundant?

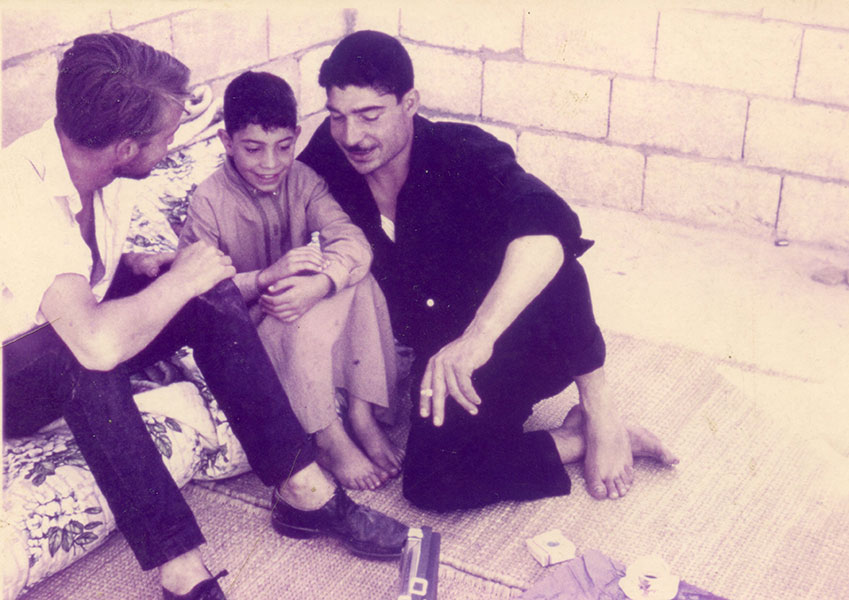

This is the season of rebirth. The young blue tits, slipping out of the nest box unnoticed, flit yellow-faced through the bushes in a constant search for insects. Young rooks and crows beg, then gargle as a parent shoves another beakful of food down a cawing red gullet. Half-fledged guillemots and razorbills launch themselves into the dangers of a new life. Trev hired a boat to watch them go and, all friends since school, invited Robert and I to join the trip. A lovely evening, I walked to meet them along Priests Way, the ancient track between Worth and Swanage once followed by the priest who served both churches. Colin Waters’ boat, ‘Sheila’s Reply’, waited for us beside the old stone quay which probably envelops the even older structure John Leland described around 1540. Its first avatar was perhaps built to serve the local marble trade during Purbeck’s 13th century boom. Everything has a story.

A fair breeze, it was choppy as we headed west past Durlston towards Dancing Ledge, where the last puffins on England’s south coast still breed. I hadn’t seen more than three this year. Late June is the best time for Purbeck puffins, when the couple of remaining pairs are joined by younger non-breeding birds checking the place out. In all, we counted perhaps seven.

From nearby Bird Cove a young chick called loudly and repeatedly, a sound reminiscent of the thrush’s song, indicating it was ready to leave the cliff. That call formed a constant background. Too young to fly, its wings are still mere flippers, great under water, barely brakes when fluttering down. It has evolved a hotline with its father, who replies with loud growls, each voice uniquely individual. They will spend some months together at sea as the chick grows and learns. As we watched the puffins nearby a great black-backed gull paddled innocently on the water, harassed by a smaller herring gull. Gulls, ravens, peregrines and even seals are alert ready to benefit from any careless young creature.

Only Trev noticed the ensuing drama. That noisy chick fluttered down. The black backed gull took off. The chick, hitting the sea near its father, came straight into a confused disturbance. Somehow, the gull flew off with the baby bird in its beak, landed on the sea to kill it then headed for the rocks for supper. The parent gave a single call, but there was silence. A short, shocking life was over.

The wind had slackened by the time we motored back along the cliffs to Durlston. There, we stopped to watch the larger guillemot ledges. The shrill chirps of several young birds rose above the growls of adults. Above, on a rock another hopeful black backed gull perched. Evening advanced and with it came chill. Now we were cold, several keen to return to Swanage but Trev’s wife, Sue, overruled us: at least we should see one chick successfully make its way out to sea. Nine o’clock came and, through a light mist, a great, red full moon heaved itself out of the sea. Still no luck.

It was worth waiting. Suddenly a chick tumbled down behind a rock. Its father, ready, coaxed it out into open water. They set off towards us. A big, white motorboat, like a rock, poses no threat to these auks. They know them as noisy but harmless. The two birds came close as I shot the best views I’d ever had of a guillemot and its kid heading out into the Channel. But accidentally I had knocked the knob on the camera to the wrong settings: not one of those pictures came out. Meanwhile, Robert successfully recorded it as a video.

At one point the parent called for attention and, as the chick watched, slowly, briefly dived. Was that a first lesson? Nervous that his chick was moving too close to us, he growled softly, almost conversationally. Obedient, it narrowed the gap from its father and together they swam out to sea, fading into the twilight. Soon the adult would moult until he, too, was confined to small flippers. Over the coming months, both birds would sprout flight feathers – primaries and secondaries - until they were full-winged. What would inspire the full-grown chick first to patter along the surface and take off? But it had grown up aware of others flying to and fro, bringing in fish. Instinctive, natural that it would gain the freedom of flight, albeit the inelegant whirring variant of a heavy, small-winged auk. Flight was not necessary for life but it was to breed. Only on the wing could it regain the cliffs and, an independent adult, take its part in the living sequence.