77. Crossing The Delta To Dacca

76. Into A New Land – Bangladesh

August 3, 2023

78. The Loss Of A Friend

October 5, 2023B angladesh consists largely of the great joint delta of Ganga and Brahmaputra Rivers, alluvial plain lined with palms and paddy. I was invited into one of the boat’s cabins where one of the two couches was empty. From the window, my hosts pointed out pulp factories fed with wood from the Sunderbans, the jungle region further downstream. There were also timber and jute mills, a power station all lining the river above Khulna. I spent much of the night watching the passing moonlit scene, a little timid of fire from the shore. They had told me that lurking Razzakars, pro-Pakistan terrorists, often fired on passing launches. Groups of lights in midstream indicated the boats of men night-fishing.

As we were about to sleep the boat negotiated a narrow channel, repeatedly running soggily aground. Was this fated to be one of those doomed journeys? But we gradually broke free and when dawn broke were chugging through wide waters where terns delicately checked, then dived and river dolphins rose and fell. A couple of small heads ploughing the smooth surface were probably terrapins. My companion, without glancing, claimed they were water rats then insisted on paying for a breakfast of two boiled eggs with an apology for toast and butter followed by tea and milk. Postwar Bangladeshi tea was revolting - rough leaf and adulterated milk.

At lunchtime, halting at Barisal, I bought bananas which contained large seeds. My companion knew better; his bananas were seedless. The river banks were sheer, some 8 ft high, and beyond them, on all sides, the country was flat, trees thinning out to reveal vivid expanses of paddy. A few scarlet-flowering trees broke the greenness. He pointed out dead forest where Pakistani troops had wiped out and burned villages. Bearded men in bright lunghis ploughed the fields or paddled little fishing boats around lines of nets. Where the river divided, sails, never white but shades of brown, seemed to glide across the fields. So we continued upriver until, in late afternoon, it spread out enormously wide. The sun fell deep orange into the haze, making way for the confronting moon, in whose grey light we overtook a file of twenty high-prowed sailing vessels, black silhouettes each some 30 ft long, slowly sliding upstream. The air was motionless. Three pairs of oarsmen worked away before the masts, a regular splash-splash which faded into our wake. The moon lay motionless in the blackening water. The next black shadow passed with a light burning, the sound of baling.

At Chandpur a line of sailing boats stretched out in the twilight, the memory of spotted watercolours of familiar English harbours which would never again be quite like this. Having overtaken us, the Rocket paddle steamer, slim, elegant and ancient, reminiscent of old time Mississippi, was tied up to the jetty. We passed onwards upstream under the rising full moon of Hindu Holi, bright over the banks and boats. I drifted back to sleep, waking in Dacca (now Dhaka) to descend the gang-plank onto dry land, a mass of rickshaws and little shops, the cooking of breakfasts amongst sleeping boys half-covered with sacks. Fleeing the rickshaw-walas and beggars in the direction I assumed would lead to the centre, I stopped after a mile at a ‘hotel’ for tea and halva. Everywhere English and Urdu signs had been obliterated, the latter most completely. Reaching New Railway Station in the hope of a nearby place to stay, I found none, not even water for washing. I gave up unyielding exploration and took a rickshaw to the Tourist Office where a man, quietly yawning, produced a map then, yawning again, a list of hotels over which he yawned again. I grew menacing. Yawning, he phoned hotels; they were all full. A Hindu peon appeared, interrupting his latest yawn, and came to the rescue. I asked if there was a dharamshala. He wrote an address and I returned to the rickshaw. There, I was welcomed but gradually realized it had become a private house. Only one room was still held by the ashram and that I could share with a pilgrim in saffron (his bed complete with saffron mosquito net) and a doctor who hadn’t been ‘home’ to Dacca since Partition. Both were from Calcutta.

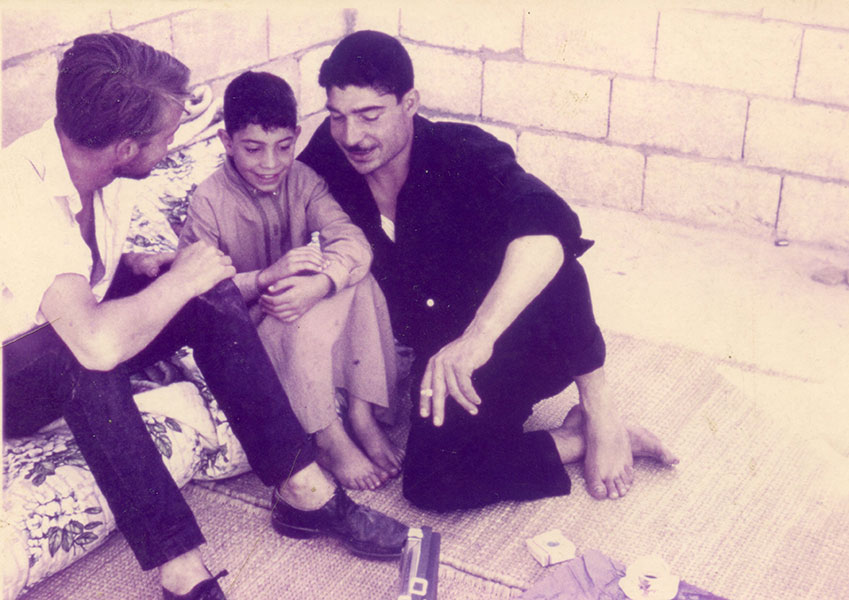

Sujit, son of the householder, became my host, brought tea and talked. His hobby was photography; I still remember some of his excellent monochrome shots. Years later, seeing one of my articles in an Indian periodical, contacted me and we caught up. Thanks to him, I found the museum, which boasted some fine textiles but little else save for the dusty, battered remnants of a Pakistani plane shoved beneath the stairs. Throughout the Hindu bazaar everything had become a delicate pinkish-mauve, the result of the morning’s Holi bombardment of colour. Everyone was tinted – clothes, hair, skin, squirt marks on the houses, even slime in the drains flowed mauve. Children sat on dyed steps comparing pink hands. The youths were mauvest of all! I passed an empty, gutted house. That, they told me, was destroyed on the 26th March night, and Pakistani troops had shot a family of nine. Some Hindus had fled to a mission school, a normal refuge during communal troubles. Troops came there, too, and shot all the men, including two of Sujit’s cousins. The attractive women were taken back to their barracks.

At the house, Sujit’s family gave me a good supper of sweet puris with different curries, including one of potatoes and cheese. They talked of the ‘troubles’. On the night of 25th March 1971 firing broke out and the sky was lit by the burning of Bengali Barracks; the Pakistani army had moved in tanks to destroy the Bengali military there. The next day total curfew was declared. News from BBC and All India Radio told of the slaughter of Hindus in their bazaar district. Soldiers came to their house and knocked down the door, but his family had escaped over the roof to the house of a non-Bengali Muslim family who helped them escape across the river. There, they sheltered in a village along with the many people of both religions who had fled the killings. A stormy night, they woke, they thought, to thunder but it was the Army was shelling refugees. Deciding to get clear of Dacca, they hired a boat upstream. Once, when it was being pulled along the bank, dacoits came to rob them. Sujit and his brother, separated from the family, tried to reach India on foot but got hopelessly lost. It was three months before they crossed the border. In India they were taken to a refugee camp, where they got passes to Calcutta. They said that the Bengali ‘Mukti Bahini’, much mentioned in the news at the time, did little in the struggle and many of them were regular Indian troops posing as insurgents. Some non-Bengalis had been murdered by the Bengali population, but only after the massacres and in villages rather than in towns.

After Liberation, his family returned to Dacca to find their business looted and their shop fired. Apparently, Pakistani troops would break into property, take any cash and jewellery, then leave the place open to be looted by dacoits. They duly photographed the looting and shot the looters, using the photographs for propaganda. In Pakistan times it had been hard for Hindus to get business and trading licenses. Now it had become easy so they have raised loans and are recouping their losses. With their house destroyed, they moved into the dharamshala. They don’t feel safe, communal feeling still remained strong. They have assets in India ready for another rising. Sujit had returned to college to find that several of his Muslim friends had been murdered by Pakistani troops. In spite of everything, he achieved a first electrical engineering.