78. The Loss Of A Friend

77. Crossing The Delta To Dacca

September 7, 202379. Back To India Via Sylhet

November 2, 2023D eath has intervened. Trev – never Trevor, but Treleven - Haysom died on 7th August. Lately, he had been ill too often. When they said he must return to intensive care, he refused. It was time to go. I saw him a few days earlier, thinking he would soon be home but, miserable, depressed, tired of hospitals, his decision came as little surprise. It softened the blow, gave his family an opportunity to say goodbye. The grief is for the loss of all his thoughts, memories, hopes and joys, the unanswered questions, but part of a full life is to quit it unfulfilled, a task left in progress. He would regret, as I regret, that imperfection, the words unsaid, the acts unacted. There is always tomorrow until, quite suddenly, the tomorrows run out.

Trev warranted a long obituary in a British national newspaper. His father was respected for his craftsmanship in stone, particularly for his restoration of the blitzed Temple Church. Trev had built on his father’s reputation. Forget the fireplaces and headstones; he worked stone for a catalogue of Britain’s most important mediaeval buildings: Westminster Abbey, the cathedrals of Chichester, Salisbury, Canterbury, Winchester, Ely, Exeter, Rochester, St David’s and Portsmouth. He also restored other prestigious churches and secular buildings as well as creating the fabric of new ones. In doing so, he gained his own renown for skill, knowledge and intellect, recognized in his honorary doctorate. His son, Mark, continues the tradition.

Trev was 81 – a lot of life to cover in a few words. I’ll stick to our friendship. We met in September 1954, both in the same class at school, both keen on the natural world. I lived in red brick New Swanage, he in stone Langton, three miles off. Our first forays together were to Chapmans Pool, one of those bays where everything washes up. With two other boys, Robert and Richard, I had taken to catching and cleaning birds maimed by oil pollution; Chapmans Pool would be a good place to find them.

Hitherto, my outings had been to woods near home, or north to the heath and Poole Harbour. In Spring, we boys watched seabirds - puffins, guillemots and razorbills – nesting on the cliffs at Durlston, climbed after gull’s eggs. Trev’s interest lay in migrants, in the cliffs further west which had those same sea birds along with ravens and peregrine falcons. My weekend focus shifted his way, to walks starting in Langton, a fair uphill cycle ride before we set out. Increasingly, from choice, Trev worked on Saturday mornings at his father’s quarry at St Aldhelm’s Head, so we’d set off from there, too.

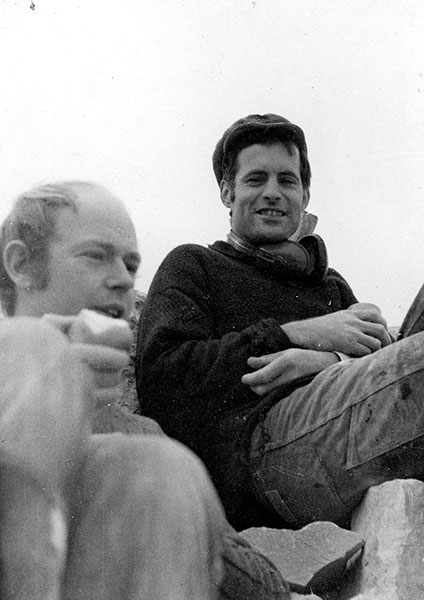

Stone featured from the start. He rarely passed a quarry, an old quarryman or mason without questions: his book, Purbeck Stone (Dovecote Press 2020), had a long gestation. At least he finished it. We examined underground quarries, low, precarious tunnels, their wooden roof-supports rotten. When a bulldozer, digging an open-cast quarry at Worth Gate, broke into an underground, we measured and mapped the network of ‘lanes’ running from the breach. Then there were the coastal cliff-stone quarries: Dancing Ledge, Seacombe, Winspit… I had a camera, but took few photographs apart from scenery or birds. Only a couple of shots show either of us completely; usually it was just Trev’s hand or knee intruding on a bird. Later, in the age of colour, I became more generous with film.

We explored the cliffs, pioneered ‘coasteering’, invaded the military firing range despite its forbidding notices and red flags. Cattle grazed there unharmed, so we, better informed, should be OK. Tyneham estate had been taken over during the war, complete with a government guarantee to return it when peace came: the fulfilment of that promise is still pending. We benefitted. A wonderful, uncultivated wilderness lay idle, nature flourishing under fire. It offered the first snowdrops, cormorants nesting on Gad Cliff, ravens hunting in pairs after their eggs. Peregrines bred there, too, feeding on migrant birds or cross-Channel groups of racing pigeons. There was a sheltering cave beneath a great rock, a little harbour for our later boats. The Great House, although damaged by firing, had yet to be robbed of its best stonework.

Despite hating school, Trev left it successful and started work at the quarry with weekly sessions at Weymouth College. Then, for his ‘City and Guilds’ course, he flourished on masonry work in Chichester Cathedral and at Oxford, where he also taught masonry. He returned to the quarry fully qualified. Miserably failing my exams, diverted by more basic interests, I spent three more years at school. Trev established a battered, clinker-built boat at Chapmans Pool, which we used for fishing and exploring the coast. Purbeck remained the primary focus of our lives from then onwards and I often worked in the quarry between long stints in India. Trev travelled when he got the chance, preferring westwards. In 1968, a sailing vessel put two unhappy crewmen ashore at Swanage. When it left, Trev had replaced one of them, bound for Los Angeles. He returned to a relationship with Wendy, a bright widow in Langton, until they drifted apart.

We had one India contact in common. The ornithologist, Horace Alexander had settled in Swanage. An exact contemporary of Adolf Hitler, he was a Quaker pacifist, conscientious objector in the First War, a follower and friend of Mahatma Gandhi and recipient of Padma Bhushan, the highest Indian honour a foreigner can attain. I looked to him for stories of the Freedom Struggle. Trev was impressed with his approach to life, even accompanied him to Quaker meetings.

Our outings continued, together or alone. In the early 1970s, we often ventured into Red Cow Country, our name for the heathland army ranges. More forbidden land, it offered nightingales, hobbies, breeding waders and nightjars. Returning from there in May 1974, we stopped at The Scott Arms. Trev said ‘I fancy the girl behind the bar’. He was shy. I wasn’t, so made conversation with Sue, then retreated. Next time we met, they were an item. They married and soon had three children. Meanwhile, I spent ever more time in India, my wall painting research there punctuated by work at the quarry.

Growing older, we spent less time together, met by chance, kept in touch by phone. Each gathered different acquaintances, but there was no replacing our common youth: we had grown alike, yet very different. When both attended the same occasion, we always drifted together. He described us as a ‘one-off’. We were fortunate to coincide.

When his daughter, Juliet, phoned to say Trev was dying, I was walking homewards, up onto the hill from Rempstone. A beautiful, still evening; three deer, one a well-horned stag, stood amongst black trees, silhouetted against a yellow sky. Looking out from the ridge, over the darkening landscape that had seen so much of our lives, I wished him well. He had chosen atheism, was going nowhere. In a world so full of mysteries, I leave all options open. Throughout our friendship, he, a year older, adopted ideas that I would later acquire - but never before he had moved on. In leaving, he has taken some magic from my life. There was a strange event at his parting. His sister, Mary, phoned next morning to say he had died. As she spoke, I noticed that a maple tree – no mean thing - had fallen in the night, gone at a time very close to his going. He would mock me, but only gently, for connecting the two events. Whether there is anything to follow death is of no concern. There is no sin, no wrath, no punishment. And if the end is all, both would agree we used our time well.