76. Into A New Land – Bangladesh

75. Bodh Gaya To Calcutta : Goodbye To The Cycle

July 6, 2023

77. Crossing The Delta To Dacca

September 7, 2023W ith summer past its prime, I left home early on the annual walk to Weymouth. Fog and drizzle obscured Purbeck’s south coast so I followed the still-clear chalk ridge. Even that would disappear into a pall of grey wetness. At the earth-walled, Iron Age, half-fort of Flowers Barrow (with each century, more of the other half fell over the cliff) the sky cleared, revealing Lulworth Castle lost in the midst of the great summer tamasha of Bestival. There was sunshine by Bat’s Head and from its ridge leaped myriads of windblown grasshoppers, polished green rose chafers fed on purple knapweed. Finally, the highpoint, that great chalk mass of Whitenothe gave way to the long descent to Osmington. Time for the blog. The journey across north India had dropped me into Calcutta and divided Bengal.

In 1971 Pakistan began to fall apart. It was always a doomed state, built on two concentrations of Muslims separated by 1000 miles of India. It must either play good neighbours or succumb. On a train through West Pakistan in late 1970, a student, a Mohajir (refugee to Pakistan from Partitioned India) spoke of an impending struggle, accurately predicting every detail. A General Election was due in March. East Bengal, then East Pakistan, holding the majority of Pakistan’s population, was united behind one party, The Awami League. It was bound to win. The leaders of politically-divided West Pakistan would not accept a Bengali-dominated government: war was inevitable. I supported the Bengali struggle from the beginning and, during the ensuing six months in India, watched it all happen: religion trumped by racism. West Pakistan leaders refused to accept the election result so, as democratically-elected prime minister, Mujibur Rahman declared East Pakistan independent as Bangla Desh. Then came bloody repression by the Western-dominated Pakistan army. But the new state was supported by India.

In August, back in London, I joined a demonstration for the recognition of Bangladesh, later returned to London to meet Horace Alexander, friend and ally of Mahatma Gandhi, who was due from Delhi. He never arrived: Pakistan attacked India, stopping all flights. So it was with a personal interest that I now left Calcutta for Bangladesh. The train, full and hot, chugged out. A Bangladeshi Hindu passenger spoke of imprisonment and violence from Pakistani troops. He seemed unsure of the truth. The last town, Bangaon provided a tea-house room with two wooden beds, each under five foot long and a rickshaw covered the remaining five miles to the frontier post. A border force must please shop-keepers. The bazaar was stacked high with Indian cloth and fruit. At a sweet-shop someone recommended one delicacy. Unimpressed, I ordered that the shop-keeper chose: was it called ‘khirrichop’? A crisp, deep-fried, ball of sweet flakey pastry with a raw centre. Delicious!

Sampan-like boats provided housing along a sluggish river choked with water hyacinth. The landscape, although flat, was beautiful, violent green with young rice, rich in trees, each village surrounded by palms, mangoes, bananas and stands of bamboo. Men followed the eternal plough through the paddy. The road, far older than the frontier, was bordered by a fine avenue of massive, ancient trees running from Bangaon to Jessore. Scribbled code ‘X-XV’ in my diary must mean the black-market rate for currency was ten rupees for fifteen taka. An Indian official said the pass to enter Bangladesh had to be issued in Calcutta. My heart sank! But the Bangladesh police weren’t bothered. Visitors could import a maximum of 20 taka: I declared 80. They altered it to 20, mentioned the half-hour time difference and I was in. Then travelling without a camera, the blog photos were mostly taken much later. I never returned to Bangladesh; the pictures show Indian Bengal.

A rough bus ran to Jessore, with a connection to Khulna. War had left many buildings newly-reroofed with tin or thatch, woodwork still scarred by fire. The curved ridge of thatched Bengali huts had been copied in local brick architecture. The Mughals copied the form, calling it bangla (Bengali), which became the root of the British ‘bungalow’. The bus often quit the road to avoid culverts under repair. A train passed, each battered truck bearing the initials of a different Indian railway region – S R, W R, E R, N R: retired Indian rolling stock.

It was very humid. Men working in the fields wore Chinese-style conical hats against the sun. A rickshaw boy pedaled me to Khulna’s steamer office. The four miles would cost me two taka. It was actually 1km and he was happy with the single taka he received. A cheap hotel offered the luxury of clean sheets. The next boat left in two days but I wanted a river journey. Where else should I go? Cox’s Bazaar? Chittagong? Ports have a charm of their own. Outside, the evening street was still busy.

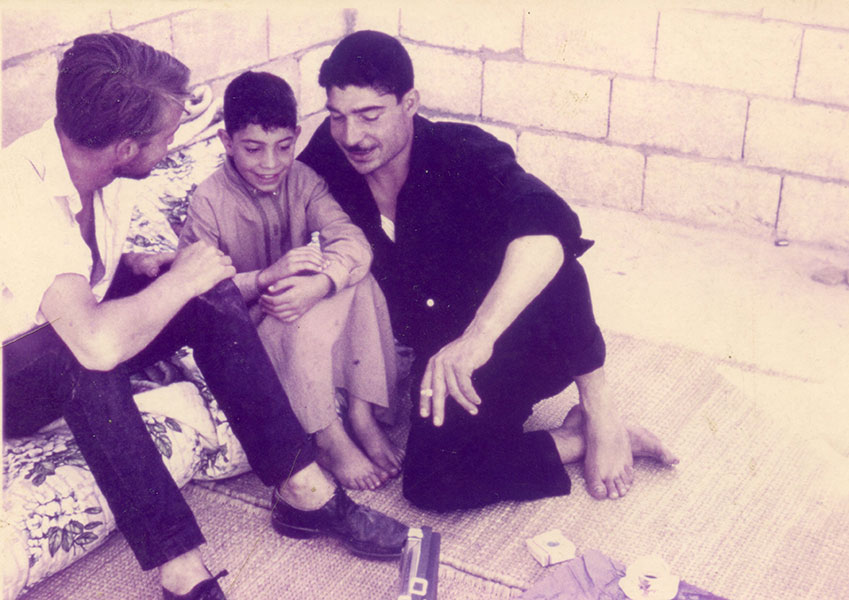

Khulna was full of beggars, the river’s edge packed with slender ‘sampans’, larger boats with a tall, vertical bow-sprit and, largest of all, high-pooped sailing vessels all standing in a blue mist of water hyacinth. Flags flapped for Sheikh Mujib’s birthday. A boy I’d met on the train to Bangaon took me to the bombed-out telephone exchange to meet his fellows. Shafique came from Leeds and was co-editor of a weekly paper and the beautiful Muli was its Hindu artist. Shafique’s family had a house in Khulna but they had spent ‘the troubles’ in a village only occasionally disturbed by Razzakars – the Bihari Pro-Pakistan militia. Meanwhile Pakistani troops looted and vandalised their house.

Shafique came to my room next morning, bearing an ink drawing of boats, a gift from Muli. Where is it now? I could have used to illustrate this blog, cherished it for years. Perhaps it is between the leaves of some rarely-consulted book. He took me down-river in a fragile, slender boat, the tide against us. Two crows jumped up and down on something floating upstream: a bloated male corpse passed close with its crow crew. I offered the boatman a cigarette. He had served in the British Army, had spent 3 days in London.

Back on land, Shafique showed me his house, still under repair, and the Post Office, now labeled only in the attractive Bengali script. Western, alien Urdu script had quickly vanished. His family gave me a typical Bengali meal of curried fish, hilsa, cachumba and rice. Even the vegetarian Hindus ate fish: in Bengal it is a vegetable. Afterwards, we went to the ferry office where they arranged a free trip on the the ‘high speed’ launch to Dacca. I had been told that the ‘Rocket’ steamer provided the only service. In the evening, he put me on board. A fellow passenger, previously working in Karachi, had managed to escape from West Pakistan three months earlier via Afghanistan with the help of Pathans. In Kabul, Indians had helped him travel to Delhi and home via Calcutta. At seven o’clock, with the moon rising, almost full, the shining river still busy with slender, black craft, the ‘high speed launch’ pulled away.