55. Dunshay Manor And Its Mystery Gateway

54. Mellow Fruitfulness

October 7, 2021

56. The Passing British On Indian Walls

December 2, 2021T he first features that strike every visitor to Dunshay Manor as they quit Haycrafts Lane to descend its drive are the house’s double gabled façade and its fine gateway, a pointed finial soaring above each pier. On my first visit, sixty years ago, the gables were faint in December darkness. As my father drove me there his headlights revealed that gateway. Elsewhere each gracious stone pier would be sufficient in itself or perhaps crowned by a round stone ball. Those wild turrets are unexpected. The gateway didn’t strike me as magnificent or as belonging to any particular era. I knew little of architecture, had nothing with which to compare it. Beyond, the house came as something of an anticlimax, too modest for such an entrance. But I was in my teens and there was a party inside. Forget the gate!

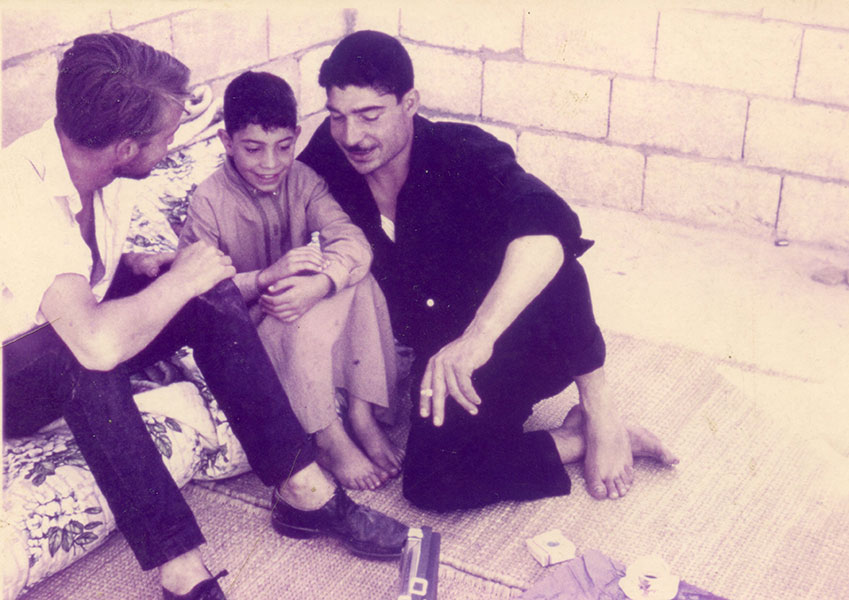

Thirty years later I settled at Dunshay. My parents had quit Purbeck but it remained my home. Researching each winter in India or Pakistan, returning home in the summer I had to find somewhere to stay. That was always difficult in the thriving tourist season. In 1988, it seemed impossible. Then, a friend suggested Mary Spencer Watson, the sculptor who owned Dunshay, might rent out her old caravan. She was amenable, the caravan battered, the rent small. I moved in next day and have been there ever since.

When Mary died, almost 20 years later, she left the estate and me to The Landmark Trust. Three of us tenants were asked to ‘skip’ the mass of papers and photographs, deemed valueless, dumped in a barn. They were a treasure trove of information on the three talented Spencer Watsons who had made Dunshay their home. All those papers illuminated my ignorance; I decided to research a book on the house and its inhabitants. The result was Purbeck Arcadia: Dunshay Manor and the Spencer Watsons.

The building itself is partly datable. On the south wall the initials of Christopher Dolling are incised into the labels of a window lintel. On another lintel the first letter of more initials is damaged - an ‘I’ it might point to John, an ‘E’ could indicate Christopher’s wife, Elizabeth. Christopher, who owned the house from 1576 to 1616, presumably built that south wall. His grandson extended the house eastwards as those two gabled wings, marking the drainpipe hopper on the new façade with I D (John Dolling), A D for his wife, Anne and the date, 1642.

Perhaps John laid out the garden with its stone-paved paths, planted the six yews, long-lived trees: two came down recently but three remain. Writers often list those piers and their pinnacles amongst his additions. They are incongruous. The monolithic piers, neatly finished with sunken panels on all four faces, were certainly not fashioned to stand against the present drystone wall, nor beside the upended slabs shown in a 19th century illustration. Perhaps they were not made for Dunshay at all or perhaps chains were to replace any fence.

Most writers side-step such issues. In 1868, Thomas Bond of Tyneham described the gate as being flanked by ‘stone piers of inelegant but characteristic form’. Twelve years later, Charles Robinson, hazarding no date, talks of ‘The strangely elegant stone piers at the garden gate’. Then, only one finial stood in place, the other having been broken off where it joined the pedestal, which was overgrown with ivy. That ill-fated pinnacle, its tip forever blunted by the fall, leaned negligently against its pier. Oddly, Nikolaus Pevsner, avoiding controversy, never noticing the gateway! Records make no mention of it and Mary’s parents knew nothing of its origin. That is how it remained.

Around 2010 I began to cycle through Dorset, carrying a sleeping bag, but no tent, and kipping where I could. Not a comfortable mode of travel, it gave freedom. Most villages treasured an interesting church, often locked. There is something ungodly about locking churches: a built-in lack of faith. Locked was the church at Charlton Marshall, 20 miles north of Dunshay, unjustly described by Sir Frederick Treves as having a ‘prim, old-maidish-look’. Its finials impressed me.

Most local 14th century churches have a square tower with, rising from each corner, a finial, its outline broken by projecting croquets. The narrow-necked finials at Charlton Marshall, clean in outline and renewed c1714, are remarkably similar to those at Dunshay. Trev Haysom pointed out that contemporary pillars inside the church closely resemble the Dunshay piers, with all four faces worked. There were similar piers with recessed panels in front of Wareham’s cliffstone Manor House (dated 1712), their height identical to Dunshay’s but achieved with two stones. Gate posts at Durnford, in nearby Langton Matravers, are meeker and not worked on all faces.

All these piers and finials are cut from Portland stone. It is difficult to differentiate fine-grained stone dug on Portland from contemporary Purbeck cliffstone, but cliffstone was close at hand and in demand in the 18th century.

The restoration of Charlton Marshall’s church 1713-15 was funded by a wealthy rector, Dr Sloper, the work attributed to the Bastard brothers, who were to rebuild Blandford after the fire of 1731. Did their masonry in the church, perhaps from stone dug at Winspit’s cliffstone quarry (then owned by the Pikes of Dunshay), inspire the Pikes and George Gould of Wareham to imitate? Did some Bastard design the Dunshay gate? Were piers left over from a plan to replace the second colonnade of the church? Perhaps all three men met by chance at Winspit quarry around 1713: Dr Sloper was there to survey the stone for his church, George Gould following progress with his new house and Robert Pike collecting the rent.

Whatever the details, surely that gateway was put up during Robert Pike’s tenure in the second decade of the 18th century. Robert inherited Dunshay after his father died in 1703 but until March 1715 his children were baptized near Clanville, his wife’s Hampshire house. From 1716 onwards they were baptized at Worth Matravers, indicating the family had moved to Dunshay. Is it presumptuous to suggest that, while smartening Dunshay against his wife’s arrival, Robert built that new gateway? Possibly – but prove otherwise!

<>*V*<>

1 Comment

I read your article about the gateposts at Dunshay Manor in the Gazetteer and then was pleased to find your blog. I visited the Manor on the Landmark Trust open day in September and was also intrigued by the piers. For me there is another connection as well as the Manor House at Wareham; I was struck by the similarity to the tower of St Luke, Old Street, which these days seems to be definitely attributed to Nicholas Hawksmoor. But I suppose it is probably quite a common architectural motif of the period.

I was horrified to hear that the Spencer Watson papers nearly ended up in a skip. How lucky that you were there to rescue them.