75. Bodh Gaya To Calcutta : Goodbye To The Cycle

74. The Demise Of Beasts & Humans

June 1, 2023

76. Into A New Land – Bangladesh

August 3, 2023I quit Benares past seven ‘sky-clad’ Jain pilgrims, renouncers of all clothing. The Grand Trunk Road was tough, much less Grand then than now, merely a narrow, battered road. Convoys of overtaking, loaded lorries tailed blinding dust, then came groups of unfinished, half-assembled vehicles heading the opposite way destined towards completion. Occasional elephants gave a lighter note to the journey. By nightfall I had covered 120 km to Sasaram where the dharamshala’s manager was missing, promising to be back in five minutes. The building was crowded, all in darkness save for a few candles. They said a fuse had blown. He appeared two hours later and the restored lights revealed me, exhausted, sitting on the rucksack in the courtyard. Alotted a room, I slept, only emerging to a dawn graced by scarlet-flowered gulmohur trees. Another tree had huge tulip-like flowers - all very beautiful.

Sasaram boasted the magnificent water-surrounded, domed tombs of the usurping Suri clan. The second Mughal emperor, Humayun, temporarily evicted by the Afghan invader, Sher Shah Suri, in 1544, and only restored to power after a decade-long Suri interregnum. He had left the Suris sleeping in these fine tombs. Having admired them, I continued east, still exhausted, assailed by a strong, contrary side-wind and struggling through heavy traffic with frequent halts. At one tea-house a Japanese youth joined me. The only other foreign cyclist I met during that whole trip, he had come from Calcutta on a much suaver bike. Together, we abused the GT Road. Frequent sections were under repair, culverts being restored, resulting in repeated diversions down from the raised highway along some rough track deep in fine dust. Each diversion was a challenge. As we parted, there was a commotion. A lorry had run over the rear end of a pig, crushing it utterly into scarlet and black mess. It stood, astonished, on its two remaining legs. Surely, neither of us has forgotten that dreadful sight.

Well before Sherghati, planned for a night-halt, the wind changed in my favour, freshening; the sky darkened to the south, clouds bearing lightning clarifying low, rocky hills. The arid landscape was punctuated by shallow wells from which water was drawn by poles weighted at one end. The flashing intensified, thunder roaring louder and closer till the sky released its torrents. Soaked, I fled for the nearest shelter, a little cycle-repairer’s shop. The owner, Kishan, made me change, brought sabji, triangular roti and hot milk, then tea, insisting I sleep in the best place.

I woke to Kishan conversing quietly with an old man before providing breakfast. There is a special blessing for all those folk along the road who dispensed generosity and hospitality with no hope of return. Their kindness was commonplace, unlikely to be returned by my compatriots! Soon I turned into the road for Bodh Gaya, often stopping to rest on the verge. Increasingly palm trees decorated the scenery and the roadside stones replaced miles for kilometers. That was a blow, having to wait a few hundred yards more for the next, reduced number. As the tower of the Mahabodhi temple came in sight the bike began to seize up, needing to be pedaled backwards before pedaling the same amount forwards. In this crippled state I reached a bungalow dormitory and collapsed for a couple of hours. Once revived, a Tibetan restaurant offering excellent jam pancakes reassured me that all was still well with the world.

Next morning, two cycle mechanics, twelve-year-old boys, threw up their hands in despair. The bike must go to Gaya, where the necessary new parts would cost at least ten rupees. They’d do what they could to get me there. In the meantime, I bought a couple the new season’s mangoes to enjoy in the temple’s peaceful, flowery gardens. Under the Bo tree saffron monks chanted, the sound soft and low but incredibly powerful. After three obeisances, an old Tibetan woman sat down near the sacred tree. Gathered from every part of the far eastern world, many of the monks were very young – one, in a maroon robe, kept peeping into my room: a lifetime commitment and he couldn’t be more than six!

The road to Gaya ran through beautiful country, tall palms against green fields, those trees full of scarlet flowers, brown hills rising around the town. To celebrate my 30th birthday, the cycle pedals gave up again and withdrawing cash at the post office proved difficult: the name on the order differed slightly from that in my passport. Returning to a good breakfast at the Tibetan place, I relaxed in the peaceful shade of the holy Bo tree behind the chanting monks before visiting Barabar Caves in evening cool.

Next day, back to Gaya’s station yard with my baggage. There, young man in a blue lungi lay on his back, dead, right arm outstretched, left on his chest, legs at attention. When the flies quit his face, he was good-looking. Around him the crowded rickshaws left a polite space. I was shocked to be so little moved. He was just there – dead, a fact. After booking the bike on the train to Delhi, he was still there, the flies thicker. Older and wiser now, I guess he was drunk. The cycle? It ended up in Haryana, in a friend’s village, to be used for ferrying goods from the bus stand to his shop.

So to Rajgir by bus, another Buddhist site, temples beside hot springs. A sign banned entry to non-Hindus. I swore; swore louder when told that only meant Muslims. A mob of joyous young soldiers ducked each other in a deep bath, their secondhand water flowing down to lower folk. The dharamshala manager was a humanist once Communist, veteran of the Independence movement and once imprisoned with the Freedom Fighter, Subhash Chandra Bose. He was an interesting man, standing for a pyramidal government in which people could affect every administrative decision.

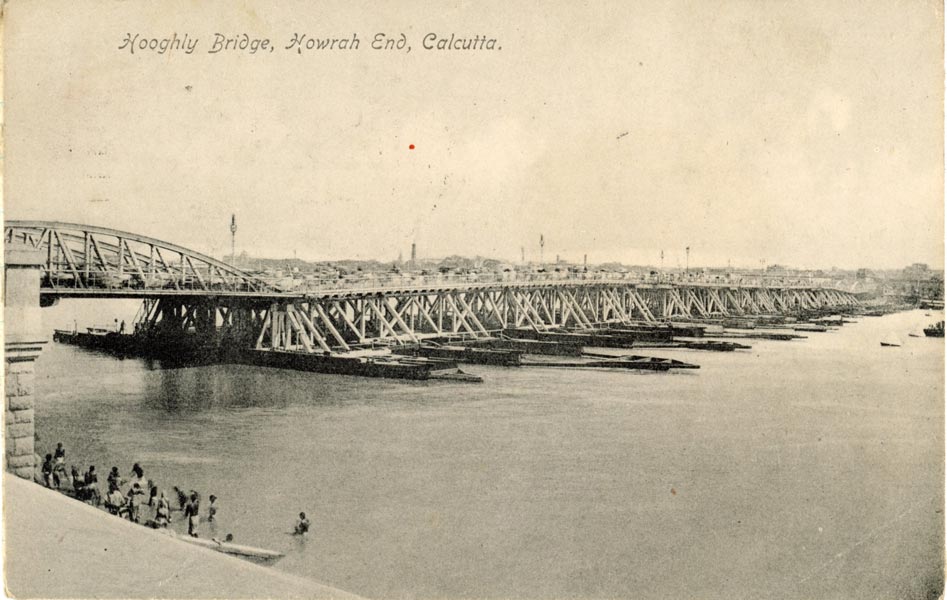

Another bus to hot Nalanda with the red-brick foundations of a Buddhist university of cells surrounding courtyards, large temples, grey schist dressings amongst the brick. Back in China, Hiuen Tsang wrote of the busy academic centre he had found there in the 7th century. A little museum displayed terracottas, bronzes and sculptures. Abandoning a diversion to Madhubani for its folk art, I decided to make for newly-freed Bangladesh, thence to Assam. The night train to Calcutta was packed, but a man got out at the small halt, removing his sleeping boy from a luggage rack. Taking his place, I woke to the slow arrival through grey dawn. Settled in gaunt Howrah Hotel, I made for the magnificent Howrah bridge among lorries, folk selling, crowds rushing, coolies sweating before their rickshaw passengers, to pass over riverside flower-sellers and wrestlers towards the city. Unwieldy sailing craft advanced on the flood tide, their crews rowing from high sterns to give some semblance of order. There were slimmer, more elegant craft, too, and river dolphins which rose and fell in the brown water. Enthusiasm returned: descending the bridge, I entered Calcutta singing.